“A richer and more perfumed case of dishonorable conduct will never, probably, be discovered in our annals.” This bracing utterance of the 1980 Supreme Court ruling in the case of Black Hills land presages one of America’s most divisive cultural hotspots today. The proposal to construct the National Garden of American Heroes alongside Mount Rushmore is reopening new wounds, new indignation, and renewed demands for justice by Native communities and their allies.

The Black Hills are more than a political stage backdrop for presidential hopefuls they’re the site of a centuries-old struggle over land, memory, and meaning. While South Dakota politicians advance the garden, Native leaders, activists, and policy analysts are struggling with what’s at stake: sacred land, historical truth, and the future of public memorials. Below are a closer examination of the most compelling dimensions of this new narrative.

1. The Black Hills: Sacred Land at the Center of the Storm

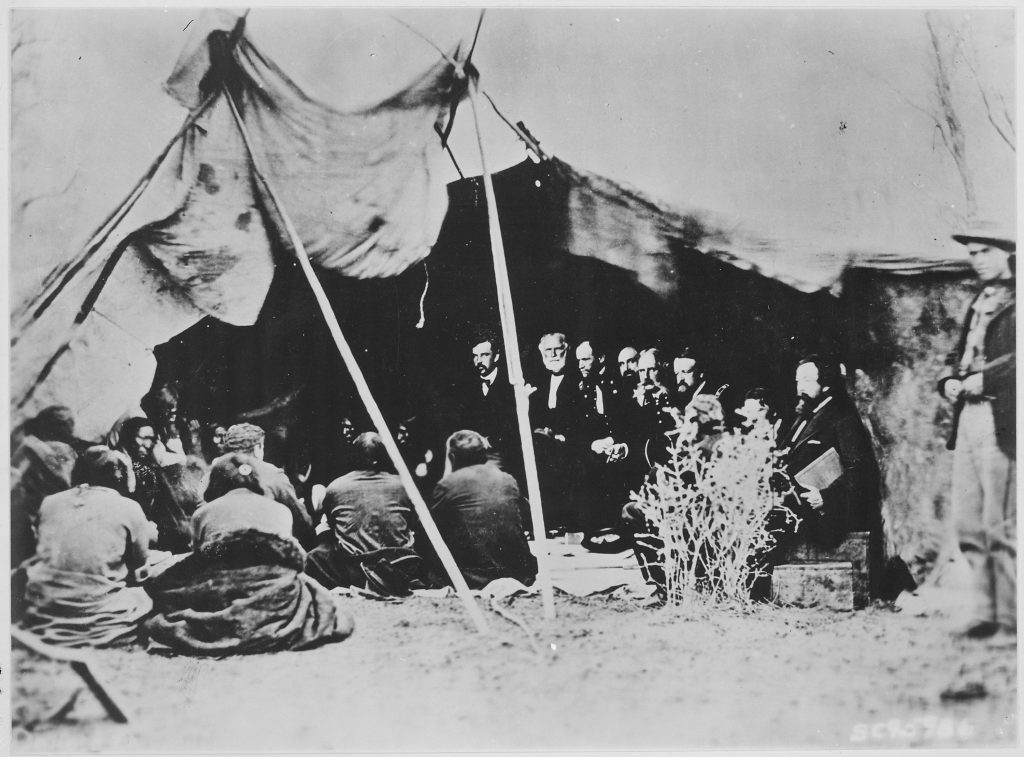

To the Lakota, Dakota, and Nakota, He Sapa are more than a mountain range. They’re spiritual birthplace, living testament to power, and site of some of the most significant events in U.S. and Indigenous history. The 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty had particularly set aside the Black Hills as “unceded Indian Territory” to be promised to Native nations. However, when gold was discovered in 1874, the United States government took back the land, resulting in wars, broken treaties, and a relocation history which still dominates the area today.

Today, the Black Hills are an international symbol of the movement to restore land taken from Native peoples. As Nick Tilsen, president of NDN Collective, states, “What South Dakota and the National Park Service call ‘a shrine to democracy’ is actually an international symbol of white supremacy.” It only fuels the sense of grievance for many Native communities to pressure this new national monument.

2. The National Garden: Vision or Flashpoint?

The presidential executive order calls for 250 life-sized statues of great Americans, a project to commemorate the country’s 250th anniversary in 2026. He described the project in terms of “a vast outdoor park that will feature the statues of the most important Americans ever.” The garden has been envisioned by its supporters, such as South Dakota Governor Larry Rhoden, as a means of paying tribute to American heroes and celebrating national ideals.

But to others, the suggested location along side Mount Rushmore is far from neutral. The location a 40-acre gift to be donated by a mining company is fueling intense resistance from Native American communities, who regard it as yet another attack on their sovereignty and spirituality. The $40 million development has cleared the House but is stalled in the Senate, its funding and construction still in doubt.

3. Broken Promises and Treaty Rights

The 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty was a seminal treaty one that was supposed to guarantee the Sioux exclusive rights to the Black Hills. But in no time, the discovery of gold rapidly unraveled those guarantees. Congress had assumed control of the land by 1877, relocating tribes to reservations and permitting white settlement in the area.

It was in 1980 that the Supreme Court decreed that the U.S. had gained possession of the Black Hills “by false means” and granted the Sioux over $100 million in reparations a figure which has risen to nearly $2 billion with interest ever since. But the Sioux have never accepted the money, feeling that “the land is not for sale.” For the members of the tribe, however, it’s not even a matter of money it’s one of sovereignty, pride, and upholding sacred oaths.

4. The Land Back Movement: From Protest to Policy

The phrase “Land Back” has become a rallying cry for Indigenous activists, reflecting both a demand for justice and a vision for the future. In recent years, groups like NDN Collective have launched high-profile campaigns to return public lands including Mount Rushmore and the Black Hills to tribal stewardship. As Krystal Two Bulls, who leads NDN’s LandBack campaign, explains, “Public land is the first manageable bite. then we’re coming for everything else.”

This isn’t a movement for property; it’s a question of reconnecting to the planet and mending intergenerational trauma. Laura Ten Fingers, a young Lakota organizer, explains, “The land owns you. It’s a way of making sure it’s protected and preserved by the people who were originally taking care of it, which is us.”

5. Environmental and Cultural Issues Collide

The planned garden is not merely a political hot spot also unsettling environmentalists with the possibility of permanent industrial development and environmental degradation. The site for the garden is owned by Pete Lien & Sons, whose quarry company has operations in the area. While exploratory drilling close to Pe’ Sla, a Lakota sacred place, has fueled concerns regarding additional desecration of ancestral lands.

To the Native people, these threats are intimate. The Black Hills are more than a backdrop for statues or excavation–they’re a living, breathing source of their spirituality and their culture. As Charlotte Coté of the Tseshaht/Nuu-chah-nulth First Nation puts it, “reclamation means being able to subsist on those lands, practice ceremonies that are sacred to those specific lands, revitalizing those relationships to those lands.”

6. Land Return: Small Victories, Big Hopes

As the fight over the Black Hills continues, there have been notable successes for tribal land restoration elsewhere. The Cobell settlement, for instance, resulted in the restoration of almost three million acres to tribal governments a close to 80 percent area roughly the size of Connecticut. Private parties and nonprofit organizations also have become involved, making it possible to return important parcels to tribes throughout the West.

But these wins, though important, merely scratch the surface of what was taken. The Sioux and others continue to fight to reclaim their holiest sites, believing that justice can never be fully served by dollars. As Nick Tilsen states, “It is not only physical land back. It is about stopping what was done to us as a people.”

7. Monuments and the Future of Memory

The National Garden of American Heroes is also framed within a wider row about who has the right to create public memory and how. Trump’s presentation of the project as a response to “a ruthless campaign to erase our history, defame our heroes, destroy our values and indoctrinate our children” has struck some chords but angered others, who understand it as a diversion from greater injustices.

For the Native people, the true work is reclaiming their histories, restorative justice for their homelands, and making sure that generations to come can give honor to their elders in their own language. As the movement increases, the question is: will America’s monuments embody a more inclusive, honest, and equitable vision of its history and future?

The battle over the National Garden of American Heroes isn’t about statues or green space it’s a mini-capsulation of America’s ongoing struggle to make sense of its past, its promises, and its future. As the war rages on, one thing is certain: the voices crying out for justice, respect, and actual reconciliation are only getting louder. For policy watchers and concerned citizens alike, the Black Hills story reminds us that the stories we tell and the land we remember are more significant now than ever before.