What if the narrative of the Gilded Age that everyone is familiar with is incomplete with some of its strongest figures? While the history books tend to place the spotlight on railroad magnates and society balls, another, equally intriguing world was living in parallel: the emergence of a Black aristocracy. These were entrepreneurs, educators, activists, and artists who, in the decades after Emancipation, built wealth, fought for civil rights, and reshaped what was possible for African Americans in America’s most economically prosperous era.

Far from a footnote, their achievements paved the way for what lay ahead the Harlem Renaissance, the civil rights battles of the 20th century. Their stories are filled with ambition, determination, and strategic brilliance, offering a fresh view of an age oft reduced to one gilded frame.

1. Converting Oysters Into High Society Money

Thomas Downing, who was born to formerly enslaved parents on Virginia’s Chincoteague Island, took a humble street food and transformed it into an elegant dining experience. By 1825, his Broad Street Oyster House in the financial district of New York was the height of luxury damask drapery, crystal chandeliers, and the city’s finest oysters. His clientele consisted of bankers, dignitaries, and even Queen Victoria, who paid him in the form of a gold chronometer watch for his shipments.

But Downing’s influence ran far deeper than the table. Beneath his velvet floors, he hid fugitives on the Underground Railroad, using his business as a front for protection against bounty hunters. He also defied segregation decades before Rosa Parks, suing a streetcar company in 1838 after being attacked for refusing to give up his seat. As historian Joanne Hyppolite suggests, Downing’s history reminds us that “culinary excellence and civil rights activism often shared the same table.”

2. Mary Ellen Pleasant’s Billion-Dollar Mindset

Dubbed the “mother of civil rights” in California, Mary Ellen Pleasant built a Gold Rush fortune. Starting as a domestic servant, she acquired investment wisdom from successful employers in hushed tones, then reinvested her earnings in laundries, boarding houses, restaurants, and even Wells Fargo stock. She was estimated to be nearly $1 billion today at her peak, historians say.

Pleasant did not just accumulate wealth she utilized it for justice. She funded abolitionist causes, provided work and housing for emancipated slaves, and, according to some accounts, contributed $30,000 to John Brown’s 1859 raid on Harpers Ferry. Her lawsuits against San Francisco streetcar corporations opened up public transit to all races in California, and showed the force of money as a civil rights tool.

3. Education as the Premier Status Symbol

Money alone was not enough for the Black elite. Education was actually the status symbol and access to power. Historian Carla Peterson states, “Since Blacks came to this country, education has always been number one.” This belief fueled patronage of institutions like the African Institute founded in 1837 by Richard Humphreys and today known as Cheyney University the oldest HBCU in America.

In the period from 1865 to 1900, a dozen or so HBCUs burst forth, matriculating doctors, pharmacists, and intellectuals who would occupy commanding seats in the sciences and the arts. W.E.B. Du Bois’s “Talented Tenth” philosophy lent form to this vision that an educated elite could raise up the whole race. In the Gilded Age, a degree wasn’t just a ticket it was a declaration of desire and cultural supremacy.

4. The Parallel Tracks of Black and White High Society

As Manhattan’s old-money families guarded their social strongholds, a Black upper class was thriving in Brooklyn communities like Fort Greene and Williamsburg. These neighborhoods, begotten in part of the post–Draft Riots flight of 1863, boasted their own business owners, cultural societies, and upscale social clubs.

The “shopkeeping aristocracy” pharmacists and grocers, as well as other entrepreneurs shared white elites’ values: refinement, philanthropy, and sociability. But systemic racism guaranteed that even the wealthiest Black families were likely to be seen, in historian Willard B. Gatewood’s words, as “a homogenous mass of degraded people.” This was a dual reality that required continual navigation of respectability politics alongside the building of spaces of self-directed distinction.

5. Shattering Barriers in the Arts and Media

The Black elite of the Gilded Age weren’t confined to business culture was shaped by them too. Women like Julia C. Collins, whose novel was published, and Susan McKinney Steward, New York City’s first Black female doctor, contributed to composite portraits like Peggy Scott on HBO’s The Gilded Age. Behind the scenes, the Black press was gaining power, with editors like T. Thomas Fortune using publications such as the New York Globe to promote racial justice.

These cultural achievements did not simply take the form of artistic expression yet were claims of defiance against a world that tried to erase Black achievement. In writing their own stories, these trailblazers ensured their communities had themselves represented with complexity and dignity.

6. Strategic Interracial Alliances

Even in a period marked by deeply entrenched racism, there were moments of authentic solidarity across racial lines. White suffragists and African American women occasionally formed close relationships, which can be accessed through correspondence stretching from abolition to the early 20th century. Working relationships, on the other hand, could lead to access: Black businessmen’s associations with white ally supporters obtained contracts, capital, and visibility.

These partnerships were not often equal, but occasionally they were reciprocal. As Peterson points out, they were a part of a “certain amount of cooperation” which allowed some Black Americans to ascend within industries otherwise closed to them.

7. Laying the Groundwork for Future Movements

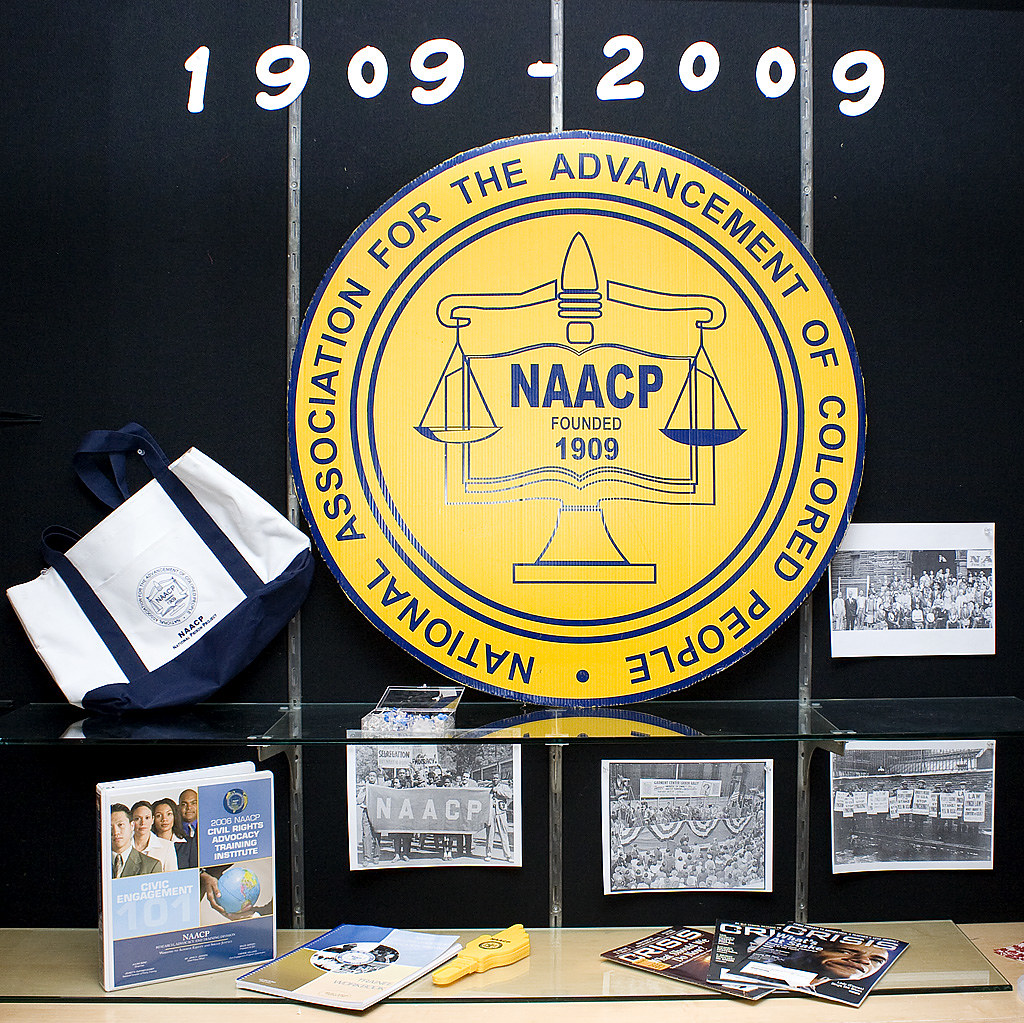

The 19th-century Black elite’s impact did not diminish with the Gilded Age it intensified. Their educational, commercial, and cultural investments provided the foundation for the Harlem Renaissance, the NAACP’s establishment in 1909, and the political activism of the early civil rights period.

“All of this would have been impossible without having lived through the 19th century Black elite,” emphasizes Peterson. Theirs is a legacy of how strategic vision, community building, and unapologetic ambition can wave forward over generations to remake the cultural and political landscape.

Gilded Age Black elite were more than mere tokens of achievement in an inhospitable era they were visionaries of a broader vision of freedom, equality, and cultural pride. Their own lives interrupt the narrow narratives of the era, revealing a simultaneous history of innovation and resistance. In honoring their triumph, we recognize the foundation they established for the movements and accomplishments that followed, and are reminded that progress is often built where history remembers not.