“We have such brief memories here in this nation, and so that’s the reason that this history needs to be remembered and told,” says Myra Armstead, a Bard professor. For most of us, the Gilded Age gives us Vanderbilt mansions, extravaganzas, and the white elite’s summer resort. But Newport, Rhode Island, was also the home to a once-thriving community of African descent with an impact that reached far beyond those shores.

Years before, when HBO’s The Gilded Age introduced figures like Peggy Scott into the world of Newport society, actual Black families were founding businesses, spearheading political campaigns, and setting the cultural tone in this venerable resort town. Their success was not replicating white decadence it was forging interdependent Black excellence saturated with activism and community.

From pioneering physicians to business magnates, these men fought to find their niche in a world that often tried to keep them out. Here are seven of Newport’s Black Gilded Age’s most epic stories.

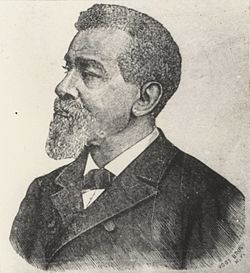

1. George T. Downing The Oyster King Turned Civil Rights Champion

A natural New Yorker, Downing was born in 1819. Downing learned a knack for business and a respect for justice from his restaurateur father. When the Sea Girt House opened in Newport, Downing began catering to the upper crust while remaining silent along lines on the Underground Railroad.

His activism never wavered. Downing spearheaded the campaign to desegregate Rhode Island public schools, petitioning for more than a decade before the 1866 triumph. He co-founded the Colored National Labor Union in 1869 and campaigned with Frederick Douglass on civil rights tours. As manager of the U.S. House of Representatives dining hall, he used his office to press for equal accommodations in Washington, D.C.

At the time of his death in 1903, the Boston Globe was referring to him as “the foremost colored man in the country.” His legacy in Newport is one of business brilliance and unapologetic activism.

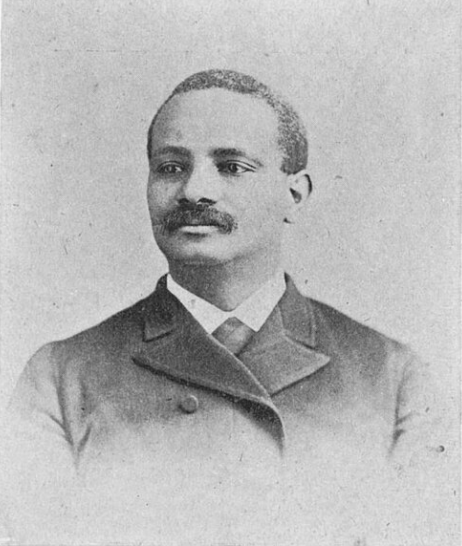

2. Reverend Mahlon Van Horne Faith, Politics, and Diplomacy

When Mahlon Van Horne came to Newport in 1869 to pastor the Union Colored Congregational Church, he had both the vision to be a pastor and the aspiration to be political. At George Downing’s urging, in 1871 he was elected to the Newport School Committee and thus became the first member of color to hold office there.

Van Horne again became a part of history in 1885 as Rhode Island’s first African American legislator, serving three terms and pushing for early civil rights legislation. His work spilled over into the rest of the state when President William McKinley made him U.S. Consul to the Danish West Indies in 1896.

Van Horne’s career was a model of what Keith Stokes refers to as “blending religion and social justice together in advancing equal rights,” prefiguring 20th-century activist clergy.

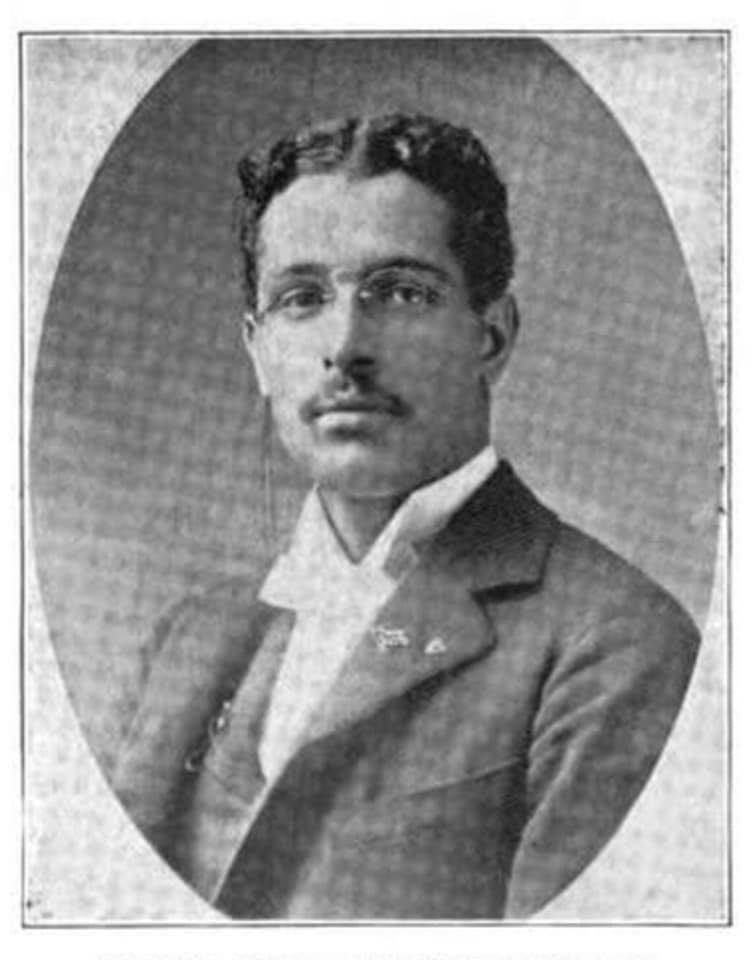

3. Marcus Wheatland Newport X-Ray Pioneer

Marcus Wheatland was born in 1868 in Barbados and graduated from Howard University Medical School in 1895, which happened to be the year Wilhelm Röntgen developed the X-ray. Wheatland was among the first to embrace the technology, the first in Rhode Island to own an X-ray machine.

Widely referred to as “the doctor of the swells,” he served Newport’s upper class while lecturing across the country on the subject of radiology. In 1909, he was chosen as president of the National Medical Association, solidifying his position as a medical and activist leader.

Marriage to Irene De Mortie, a lady who was herself a granddaughter of George Downing, united two of the top Black families of Newport. Dr. Marcus Wheatland Boulevard is a testament today to his milestone achievements.

4. Dr. Harriet Alleyne Rice A Woman of Courage

Harriet Rice shattered doors as the first African American graduate from Wellesley College in 1887 and earned her M.D. from the Women’s Medical College of the New York Infirmary in 1891. Excluded from American hospitals due to both being black and female, she practiced at Hull House in Chicago and ultimately established her own Newport practice.

During World War I, Rice served over three years in France, caring for wounded soldiers. For her “immense services” and “devotion and ability,” the French government awarded her the Medal of Gratitude.

Her candid reflection in 1935 “Yes! I’m colored which is worse than any crime in this God blessed Christian country!” underscores both the obstacles she faced and the resilience that defined her career.

5. Christiana Carteaux Bannister “Hair Doctress” and Abolitionist

Christiana Bannister established a successful salon business in Providence and Boston and earned the nickname “Hair Doctress.” Her earnings helped finance the art career of her husband, Edward Bannister, who became a successful Black painter nationally.

Outside of the business world, Christiana was an ardent abolitionist. She advocated for the 54th Massachusetts Regiment in the Civil War, campaigned for equal pay for Black troops, and established the Home for Aged Colored Women in Providence.

Edward once commented, “I would have made out very poorly had it not been for her,” referencing her partner and force in her own right.

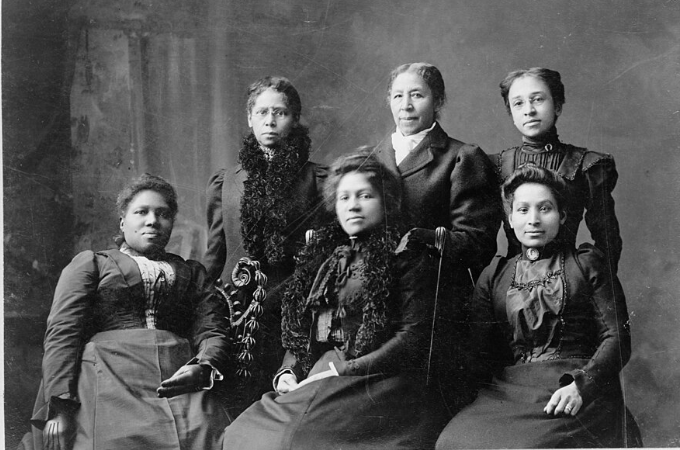

6. Mary H. Dickerson Club Founder and Entrepreneur

Arriving in Newport sometime around 1865, Mary Dickerson established a dress shop on Bellevue Avenue, the first Black woman to be the owner of a retail business there. She catered to Newport’s wealthy summer residents and acquired large parcels of property.

In 1895, she founded the Women’s Newport League, and a year later co-founded the Northeastern Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs with Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin. These organizations tackled pressing issues like anti-lynching advocacy and early childcare.

Dickerson’s blend of style, business savvy, and activism made her a central figure in Newport’s Black Gilded Age.

7. The Free African Union Society Roots of a Community

Newport’s Black leaders’ success did not come overnight. They were founded on pillars such as the Free African Union Society, established in 1780 in Abraham Casey’s house. It was the first African American mutual benefit society in the United States.

From these early networks developed churches, benevolent societies, and commercial ventures that united Black communities from Boston to Philadelphia. By the late 19th century, Newport’s African heritage residents were not only successful locally but shaping national debates regarding civil rights.

As Keith Stokes describes, they “did not see themselves as chocolate-covered Cornelius Vanderbilts” but as members of a broader African diaspora dedicated to collective advancement.

Newport’s Gilded Age wasn’t just a time of glittering parties and marble houses it was also a time of innovation, tenacity, and African ancestral families forging communities. Their lives pull against the reductive outlines of history, proving that Black excellence flourished in environments stereotypically thought to be white. By remembering and retelling these lives, the history of the Gilded Age is richer, more filled out, and considerably more inspiring.