What if a wall of water taller than the Statue of Liberty came crashing toward the coast leaving minutes, not hours, to act? That’s not a disaster movie plot. It’s a scenario scientists say is entirely possible for parts of the United States.

A fresh wave of studies has focused on the Cascadia Subduction Zone a behemoth fault system running from northern California up to Canada as being among the most perilous seismically active regions on the planet. Scientists say it might trigger a mega‑tsunami with waves reaching 1,000 feet, reconfiguring coastlines and towns in mere seconds.

For those living on the coast, emergency managers, and policymakers, knowing the magnitude, velocity, and reach of this threat isn’t theoretical it’s a matter of survival. Here’s what the new science teaches us about the dangers, the past, and the imperative for preparedness.

1. The Cascadia Subduction Zone’s Catastrophic Potential

Running approximately 700 miles off the coast of northern California to British Columbia, the Cascadia Subduction Zone is where the Juan de Fuca, Explorer, and Gorda plates are subducting under the North American plate. This geologic configuration has the potential to create magnitude 8–9 earthquakes equivalent to the 2004 Indian Ocean and 2011 Japan catastrophes.

Based on the findings of Virginia Tech scientists, there’s a 15% probability of a magnitude 8.0+ earthquake occurring here in the next few decades. The ground shaking may last six minutes or so, directly causing a tsunami that crashes into the Pacific Northwest within 15–30 minutes. Coastal cities may be completely annihilated before a mass evacuation can be done.

2. Waves That Could Tower Over Skyscrapers

Although most tsunamis have runups of a few meters, the case Virginia Tech modeled posits that extreme instances might reach 300 meters approximately 1,000 feet. Even more modest predictions by the Cascadia Region Earthquake Workgroup foresee waves of 30–40 feet in parts of the region, still sufficient to destroy infrastructure.

Wave height varies with local bathymetry, shoreline geometry, and subsidence caused by the quake. As the Green rule describes, when water gets shallower close to shore, wave height can increase catastrophically particularly in harbors and bays where energy is focused inward.

3. No Time for a Warning

In contrast to far-off tsunamis, which may permit hours for warnings, a Cascadia‑produced wave would reach certain communities in less than 20 minutes. That provides hardly enough time to feel the quake, grab what one needs, and flee to higher ground.

The National Weather Service’s tsunami advice emphasizes that evacuation should start at once in the event of severe coastal shaking prior to any official warning. As the rule of thumb states: if you observe the sea pulling back quickly, it’s too late to try and outrun the wave by then.

4. The Last Big One Was in 1700

On January 26, 1700, a magnitude 9.0 earthquake hit Cascadia, lowering the coast several feet and sending a tsunami out across the Pacific. Later, Japanese documentation of an “orphan tsunami” that evening waves without a local earthquake were correlated with this event.

Geological proof, such as “ghost forests” of dead trees and sand deposits in marshes, verifies at least 43 significant quakes here over the past 10,000 years. The 325-year hiatus since the last one indicates stress is accumulating, so another event becomes more probable.

5. Alaska and Hawaii Aren’t Safe Either

Despite being distant from Cascadia, Alaska and Hawaii are also under high tsunami threat from their own seismogenic sources. Alaska’s 1964 magnitude 9.2 earthquake created a Pacific‑wide tsunami that destroyed Crescent City, California, and killed as far as Oregon.

Hawaii’s history includes deadly teletsunamis from Chile, Alaska, and Kamchatka, with runups exceeding 50 feet. Since 1811, Hawaii has experienced at least 32 tsunamis over one meter high, underscoring its vulnerability.

6. Beyond the Wave: Secondary Disasters

The devastation doesn’t stop when the water goes out. As the Coastal Wiki observes, tsunamis can ignite fires, spill hazardous materials, and create landslides. Saltwater flooding can destroy croplands for years, and debris vehicles, trees, buildings makes the water a battering ram.

Damage to infrastructure might sever power, water, and communications for weeks. Relief to stranded coastal communities could be delayed by blocked roads and ruined ports.

7. Preparedness Is the Only Defense

Scientists all concur that it’s not a question of if, but when, the next Cascadia mega-quake and tsunami will hit. Virginia Tech study lead author Tina Dura said to the New York Post, “The growth of coastal floodplain following a Cascadia subduction zone earthquake has not been previously measured, and the effects on land use could extend the time required for recovery substantially.”

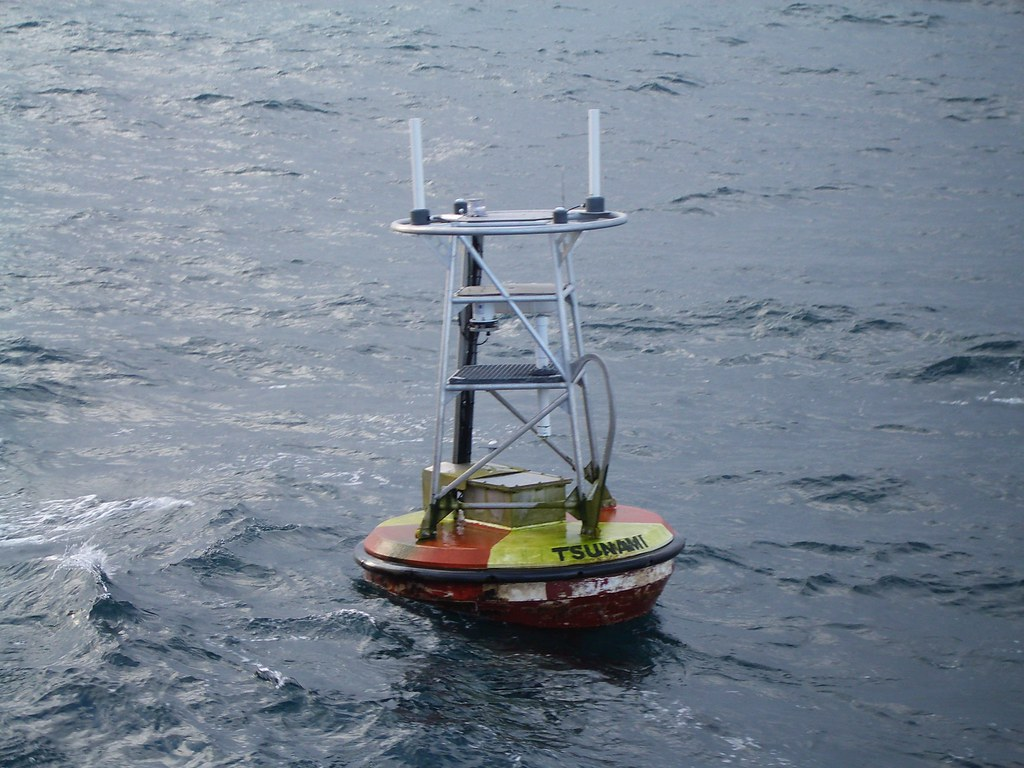

Work in progress involves mapping flooded areas, placing warning systems, and fortifying building codes. In Oregon, residents are encouraged to be “2 Weeks Ready,” with enough supplies to get through without external assistance. For beachfront areas, drills and well-defined routes to evacuate can be a matter of life and death.

The science describes a sobering scenario: a Cascadia mega‑tsunami could come with barely any warning, unleashing devastation on a scale that only a handful of disasters have had. But information is power. With an awareness of the threat, investment in resilient buildings, and a preparedness culture, coastal communities can make a virtual certainty a survivable one.