The conversion of Fort Bliss into the country’s largest detention center for immigrants has evoked strong feelings, particularly among Japanese American groups that recall its history during World War II. This huge tent city in El Paso, Texas, with a capacity to hold 5,000 detainees and costing $1.2 billion, now sits at the focal point of an argument about history, justice, and the direction of immigration policy at a national level.

1. A Site with a Heavy Past

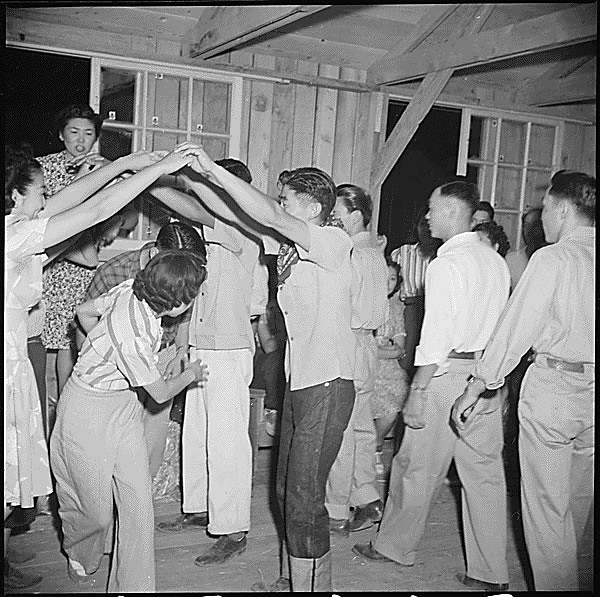

Eight decades ago, Fort Bliss was a wheel in the Japanese internment machinery. Records assembled by Ireizō indicate that at least 113 first-generation Japanese Americans were detained there before being transferred to other camps. Historian Brian Niiya, whose grandfather was incarcerated in six camps, cautions, “It’s important to look to this past to maybe try to understand what’s going on in the present and what the end results could be.” The center also held German and Italian immigrants, all under the 1798 Alien Enemies Act.

2. Parallels That Can’t Be Ignored

Activists such as Ann Burroughs, head of the Japanese American National Museum, view “the invocation of national security reasoning to condone mass incarceration today” as a reincarnation of the rationale of WWII-era removals. “It is unfathomable that the United States is again constructing concentration camps, ignoring the lessons of 80 years ago,” she stated. The American Civil Liberties Union has characterized Fort Bliss’ new mission as “another shameful chapter” in its history.

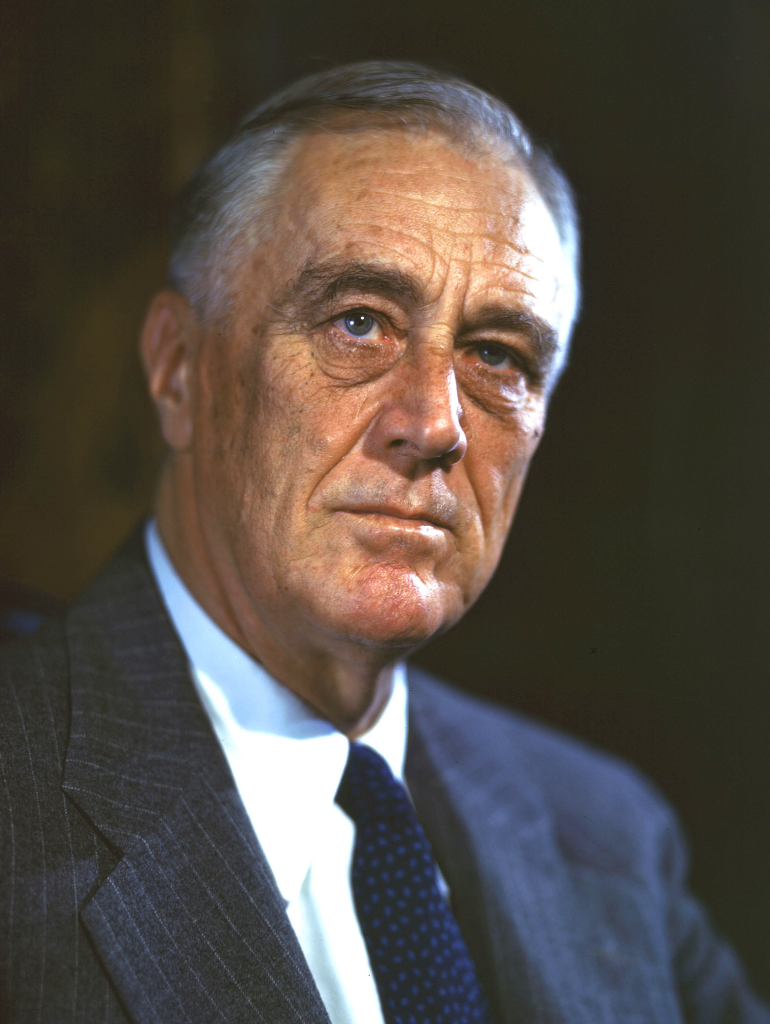

3. The Alien Enemies Act Returns

President Franklin D. Roosevelt under Pearl Harbor invoked the Alien Enemies Act to detain Japanese immigrants and seize property.

In 2025, Donald Trump invoked the same statute against Venezuelans accused of being gang members, sidestepping judicial review an unprecedented peacetime application. Legal analysts caution that the act allows detaining and deporting civilians “on the sole basis of their heritage,” and civil rights organizations are urging repeal via the Neighbors Not Enemies Act.

4. Conditions Behind the Fences

The Fort Bliss tent city, or Camp East Montana to locals, has attracted attention for conditions recalling earlier humanitarian disasters. In its deployment under the Biden administration as temporary shelter for unaccompanied children, a federal probe revealed that new hires and inadequate case management left young people waiting weeks for news, causing distress, panic attacks, and in some instances, self-injuring. “They had a sense that they had been forgotten,” one worker remembered.

5. The Human Cost of Detention

Study reveals that immigration enforcement policies instill chronic fear and instability for millions, particularly children in mixed-status families. Forced family separations are linked to anxiety, depression, developmental regression, and downward academic trajectory. Detention threat alone can lead to school absenteeism and social withdrawal. According to psychiatrist Lisa Fortuna, “Stable attachment to a caregiver is foundational to a child’s mental health,” and detention undermines that foundation.

6. Community Memory and Resistance

For elders like 91-year-old Kashiwagi, who was incarcerated during World War II at Tule Lake, the reactivation of Fort Bliss as a detention center is déjà vu. “Here we go again,” she said, pointing to a childhood scar from camp. Organizations like Tsuru for Solidarity are organizing with Latinx, Black, and Indigenous supporters to provide sanctuary, legal support, and rapid response during ICE raids. “We really want to rally all Japanese Americans to come together,” said KC Mukai, co-chair of the Japanese American Youth Alliance.

7. Militarization and Secrecy

Detractors say locating detention facilities on military bases decreases transparency and heightens the possibility of abuse. The ACLU deems Fort Bliss “a calculated move to militarize immigration enforcement, reduce transparency, and fast-track deportations with minimal accountability.” Rep. Veronica Escobar has expressed concerns about private contractors operating the site, cautioning that “standards too easily slip” when profit is put above care.

8. Learning from History—Or Repeating It

Historians used to assume that education about Japanese internment would deter its repetition. But, as Niiya considers, “Perhaps we can’t say that anymore.” The similarities mass detention of targeted groups, invocation of the Alien Enemies Act, and national security rhetoric are apparent to the past’s survivors.

The narrative of Fort Bliss in the present is not one of a single detention facility. It’s one of whether America can come to terms with its past and its current, and whether societies can use bitter memory as a vehicle of justice and human rights protection.