What if all the ancient papyrus scrolls, crumbling monuments, and forgotten myths drew the same breath? For centuries, the Exodus has been a magnet for debate myth, history, or something in between? Though critics typically cite the lack of physical remains, increasing archaeological and textual evidence is quietly shifting the conversation.

New finds in Egypt and profound excursions into ancient books have uncovered stunning parallels between the biblical account and historical events recorded by Egyptian scribes and later historians. Such finds do not merely present interesting facts they span timelines, names, and cultural customs in a way that renders Exodus denial more challenging than ever. Listed below are seven of the most convincing pieces of evidence that bring the story to life.

1. Manetho’s Account of Osarseph and the Exodus Parallel

Egyptian historian Manetho, as Josephus preserved him, presents us with a vivid narrative: There was a revolt in Egypt by a group of lepers, led by a priest named Osarseph, against Pharaoh Amenophis. They allied themselves with the Hyksos of Canaan, desecrated temples sacrilegiously, and resisted Egyptian religion. Osarseph took the name of Moses. This history mimics the biblical Exodus in eerily precise detail a repressed minority group coming together with others, struggling with Pharaoh, and ultimately being driven out. Scholar Thomas Römer noted that Pharaoh’s fears in Exodus 1:9–10 fears of an internal group uniting with external enemies are nearly identical to Manetho’s narrative.

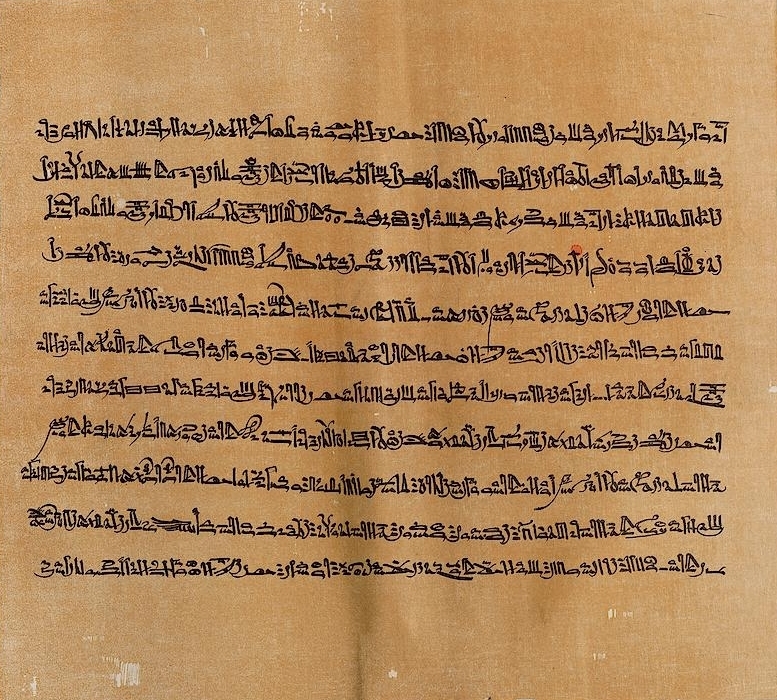

2. The Great Harris Papyrus and the ‘Haru’ Ruler

One of the oldest Egyptian papyri to have survived, the Great Harris Papyrus, documents a turbulent period after Queen Tausert died around 1188 BCE. It reports upon a self-styled leader, an “irsu,” of Canaanite or Syrian origin “Haru” was his name who seized power, defied Egyptian gods, and levied taxes on the land. He brought in foreign allies, similar to the Exodus account of foreign reinforcements. Finally, Pharaoh Setnakhte restored order, defeating the foreign leader and exiling his followers. The parallels with the Bible’s version of a foreign-inspired rebellion and restoration by God are striking.

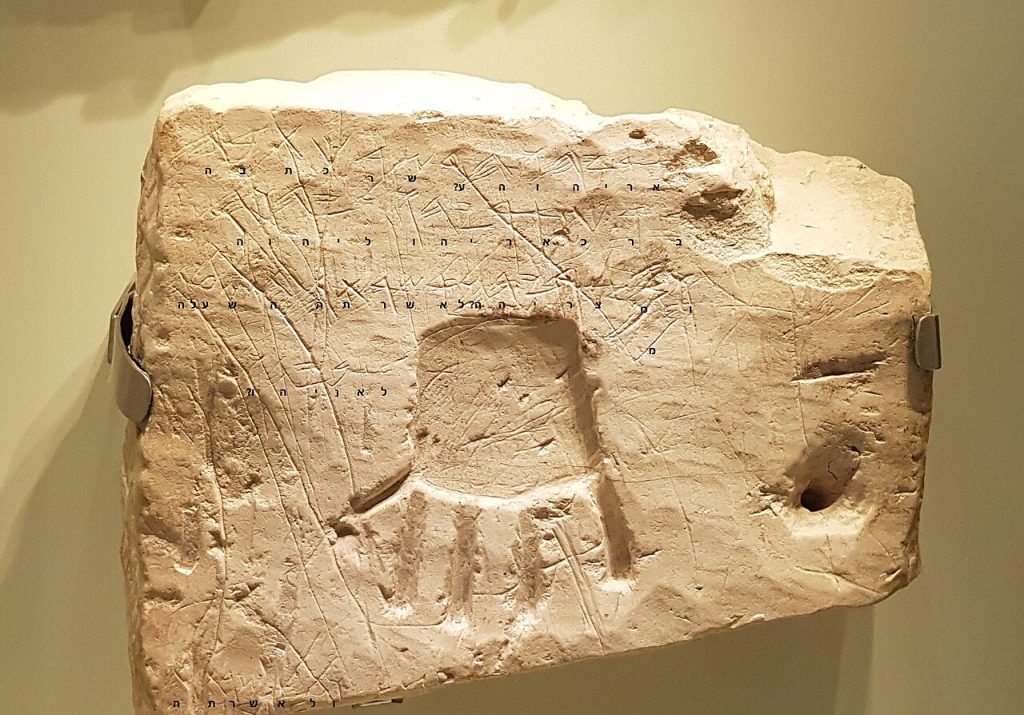

3. Flight ‘Like Swallows’ of the Elephantine Monument

One of the monuments from Setnakhte’s second year, on the island of Elephantine, lyrically speaks of his enemies departing “as the swallows depart before the hawk.” These enemies, paid in gold and silver to participate in the rebellion, abandoned their treasures when they departed. The poetic touch here is echoed in Exodus 12:35–36, when Egyptians give gold and silver to the Israelites as they depart. The application of imagery of fearful flight reinforces the poetic meaning of the scripture.

4. Levites as the Exodus Core Group

Biblical scholar Richard Elliott Friedman suggests the Exodus may have involved a smaller group the Levites rather than the entire Israelite population. Levites, including Moses, bore Egyptian names like Phinehas and Hophni, practiced Egyptian customs such as circumcision, and designed the Tabernacle in a style matching Pharaoh Rameses II’s battle tent. These cultural fingerprints point to a genuine Egyptian origin for this group, aligning with the idea that they carried the Exodus memory into Israelite tradition.

5. The Song of Miriam and the Song of Deborah

Two of the most ancient books of the Bible are complementary stories. The Song of Miriam, which takes place in Egypt, celebrates the deliverance of a people but does not refer to all Israel. The Song of Deborah, composed in Canaan, makes no mention of the tribe of Levi. This silence supports the theory that the Levites were present in Egypt in the time of Deborah, lending credence to the idea of an incoming stagger and the later assimilation of the Exodus into Israelite national consciousness.

6. Egyptian Cultural Traces in Israelite Worship

Egyptian influences are seen in Levite-written books of the Bible. They emphasize circumcision, welcoming aliens, and Egyptian-style Tabernacle architecture. Non-Levite books omit these elements. This cultural borrowing selectively suggests that only Levites had lived in Egypt, bringing its customs with them into Israel’s religion.

7. The Unification of El and Yahweh

When the Levites united with the Israelite tribes, they brought in the cult of Yahweh, while the tribes venerated El, the Canaanite highest deity. Instead of having two gods, they equated El and Yahweh. Such syncretism of theology, as found in Levite-written works like Exodus 3:15 and 6:2–3, was the focal step in the formation of monotheism. If the Levites had not migrated to Israel from Egypt, the path to one God in Israelite religion would have been longer or perhaps never would have reached at all.

No single artifact can “prove” the Exodus categorically, but the convergence of Egyptian accounts, biblical texts, and cultural clues creates a mosaic that’s hard to ignore. These discoveries don’t simply verify a story they illuminate how history, religion, and identity converged in ways still shaping belief today. To those who hold the Exodus to be pivotal, the past is speaking and it’s saying there’s more to the narrative than cynics might suspect.