For nearly 100,000 years, the quiet darkness of Tinshemet Cave, in central Israel, kept its secrets sealed. Now, under the slow, painstaking work of archaeologists, it is yielding a revelation that challenges long-standing ideas about when and with whom human ritual began: five deliberate burials, deep within cemented sediments, each containing pigments, artifacts, and evidence of ceremonial care, place this site among the oldest burial grounds on record.

1. A Frozen in Time Burial Site

In this cave, burials, including two complete skeletons and three skulls, were placed in shallow pits, bodies curled in fetal positions, with hundreds of objects having absolutely no utilitarian purpose. According to Yossi Zaidner, co-director of the excavation, they “were laid into pits and arranged in a fetal position, acknowledged as a burial position.” The careful placing and preservation suggest immediate burial upon death to avoid scavengers and the elements.

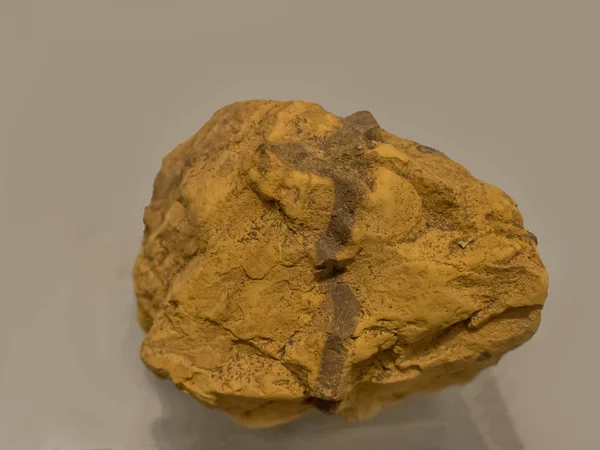

2. Pigments With a Purpose

More than 7,500 fragments of ochre, ranging in color from deep red to orange, were recovered, with many of them having been sourced from distances greater than 60–100 kilometers. Some pieces showed heating to enhance their color, as also observed in Qafzeh and Skhul caves. One big piece of red ochre was found between the legs of an individual known as Tinshemet 2. The deliberate placing, together with obtaining material from distant sources, indicates symbolic intention-what the researchers call a marker of emerging cultural identity.

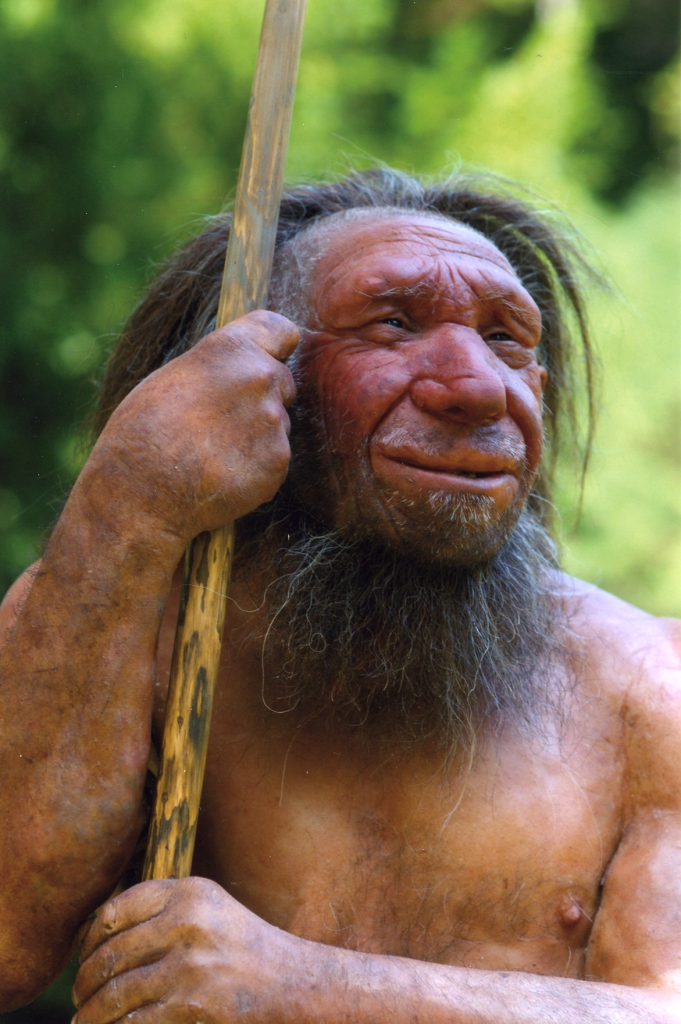

3. Shared Rituals Across Species

The remains represent both Homo sapiens and Neanderthal-like hominins but possibly other archaic groups, too. In any case, at that time, the Levant hosted at least three different human populations. While morphologically distinct, they seem to have shared one behavioral package-from hunting strategies to funerary customs. As Prof. Israel Hershkovitz explained, “These groups interacted and developed a homogeneous culture. However, from a biological perspective, for developing homogenous characteristics, it takes much more time.”

4. Echoes of Other Ancient Burials

The Tinshemet finds resonate with other Middle Paleolithic burials, such as at La Chapelle-aux-Saints in France, where Neanderthals were intentionally interred, and with the Upper Paleolithic Eurasian graves that sometimes included ornaments and pigments. However, as studies of early human burials worldwide have demonstrated, the majority of burials were relatively simple, which implies that sumptuous burials were very rare anomalies. The regularities of ochre use and body positioning in Tinshemet imply a shared, deeply embedded tradition rather than separate, independent actions.

5. Symbolism in Stone and Bone

Besides the human remains, archaeologists discovered basalt pebbles, animal bones, and antlers-things not functional in daily subsistence. Their presence in graves reflects symbolic behavior similar to that observed in both early Homo sapiens and Neanderthal contexts. In a number of cases, ochre was probably applied to the body during funerary rites, marking group identity and perhaps life-after-death beliefs.

6. Technology as a Cultural Bridge

The stone tools recovered from the site reveal the centripetal Levallois technique, which has been shared throughout the Levant during the mid-Middle Paleolithic. This technological uniformity of the Middle Paleolithic across different human species also supports the notion of high inter-population connectivity. As Prof. Zaidner puts it, “Our data show that human connections and population interactions have been fundamental in driving cultural and technological innovations throughout history.”

7. The Cave as a Social Anchor

The clustering of the burials raises the possibility that Tinshemet served as a dedicated cemetery-a place to which the living returned to honor their dead. Such a role would imply strong communal bonds and shared ritual space, reinforcing social cohesion in a challenging Ice Age landscape.

8. A Global Context for Symbolic Behavior

The symbolic use of ochre is not unique to the Levant. For instance, Neanderthal sites in Crimea also have crayon-like ochre tools shaped for mark-making, while African Middle Stone Age sites reveal long-distance pigment transport and use in personal ornaments. The convergence of these behaviors across continents and species supports the gradual build-up of symbolic thought in multiple populations long before the Upper Paleolithic “creative explosion.”

9. Rethinking Human Interaction

Far from the old narrative of relentless conflict, the evidence at Tinshemet suggests cooperation, sharing of knowledge, and even interbreeding between groups. Hershkovitz upsets the warfare model: “It is possible that in the Middle Paleolithic, hominins did not care about differences and coexisted peacefully.” The work at Tinshemet Cave is far from over.

With much of the site still unexcavated, each carefully removed layer could reveal even more about how early humans-regardless of species-faced mortality, expressed identity, and built the shared rituals which would echo through tens of thousands of years.