“What we have here is probably the best opportunity that has ever arisen yet to finally close the case,” said Richard Pettigrew, executive director of the Archaeological Legacy Institute. His words are heavily laden with nearly nine decades of speculation, searches, and hope about the disappearance of Amelia Earhart, a figure whose daring spirit still inspires aviators and adventurers worldwide.

1. A Mystery Frozen in Time

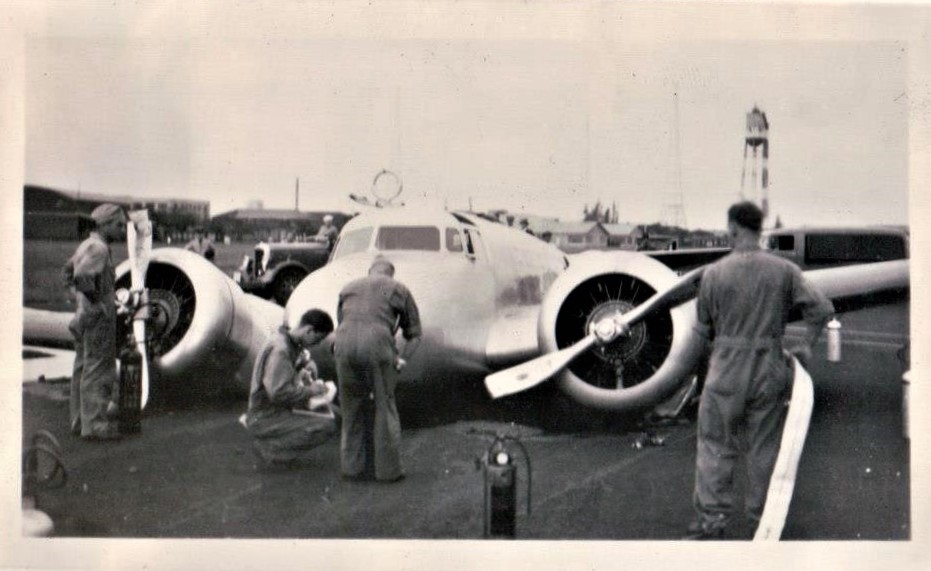

Amelia Earhart, along with her navigator Fred Noonan, disappeared over the Pacific on July 2, 1937, in an attempt to be the first woman to fly around the globe at the equator. Their Purdue Research Foundation-funded Lockheed 10-E Electra never came back. Theories have abounded over the years, from a crash into the sea to capture by foreign forces; one theory, however, has endured: Earhart landed on Nikumaroro, a remote, uninhabited island today included in the Republic of Kiribati, and died there.

2. The Taraia Object

The latest expedition targets a submerged anomaly in Nikumaroro’s lagoon called the Taraia Object. First identified in 2020 by U.S. Navy veteran Mike Ashmore while scanning through Apple Maps, the object has the elongated, reflective shape of the fuselage and tail of an Electra. Historical aerial images reveal that it has lain in the same position since 1938, maybe exposed after storms had shifted sediment. Pettigrew thinks this could be Earhart’s aluminum wreckage floated into the lagoon when the plane broke apart on the reef.

3. Evidence That Fuels the Search

The case for Nikumaroro is built on several lines of converging evidence: radio bearings recorded by the U.S. Navy and Coast Guard, which converge near the island; bones found in 1940 whose measurements match Earhart’s more closely than 99 percent of people; artifacts from the 1930s, including a woman’s shoe, compact case, and freckle cream jar; and the Bevington Object, a photographic anomaly resembling landing gear captured just months after the disappearance. The Taraia Object may be the final piece needed to confirm the theory.

4. The Expedition Plan

A team of 15 from ALI and Purdue University will leave Majuro in the Marshall Islands and sail 1,200 nautical miles to Nikumaroro. The mission will include six days of travel each way and five days on-site. Initial work will include drone footage, still photography, and remote sensing with magnetometers and sonar. Promising results will be followed with a hydraulic dredge removing sediment and revealing the object’s shape. Security measures coordinated with Kiribati’s government will protect the site from interference.

5. Purdue’s Lasting Relationship

She joined Purdue in 1935 as a career counselor and technical advisor in aeronautics, to urge more women to consider aviation and STEM careers. The university paid for her Electra-“Flying Laboratory”-with support from benefactors and corporations, and she had planned to turn the aircraft over to Purdue after her flight for ongoing research. Today, Purdue remembers her legacy in names of facilities and programs and, this year, the opening of the Amelia Earhart Terminal at Purdue Airport. If the Electra is located, Purdue would like to bring it home, as Earhart had planned.

6. Rival Theories and Skepticism

Not all researchers buy into the Nikumaroro hypothesis. Ric Gillespie of The International Group for Historic Aircraft Recovery thinks the object is a pandanus tree, not wreckage, and says the plane was destroyed in the surf. Meanwhile, the ocean exploration company Nauticos continues to comb the seafloor near Howland Island, using reconstructed radio transmissions from Earhart’s final hours to guide the search. These parallel pursuits reflect the stubborn intricacy of the mystery.

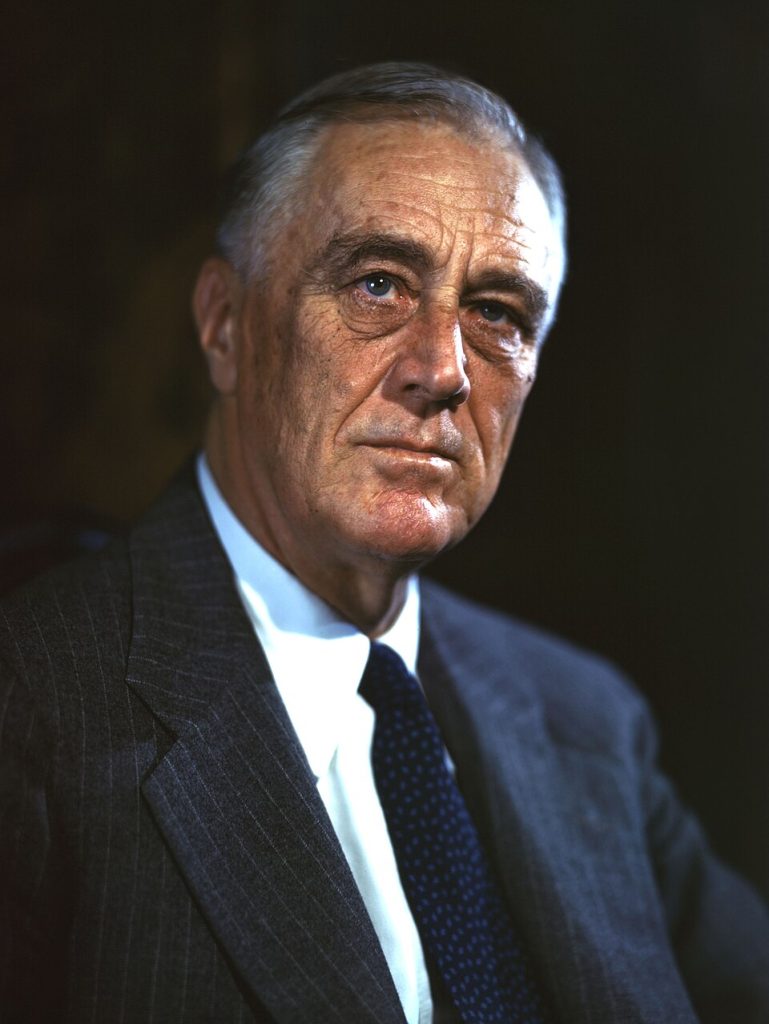

7. Aviation Legacy of Earhart

Earhart’s feats rewrote many people’s perception of women in aviation. First woman to fly solo across the Atlantic, first person to solo from Hawaii to California, one of the founders of Ninety-Nines, the organization that promoted women in flying-she did it all. Her words to President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1936-“women now and then have to do things to show what women can do”-have remained a rallying cry for equality in the skies. Figures like her made the way easy for later pioneers, be it Judith Resnik or Bessie Coleman, whose bravery keeps inspiring.

8. Human Factors

For Ashmore, who found the Taraia Object, the search is a personal passion. “It just stuck with me,” he said of hearing Earhart’s story as a child. For Pettigrew, it is about evidence and closure. “The only thing I’m absolutely certain of is that we have to go and look,” he said. For Purdue’s team members, including astronaut Sirisha Bandla, it is a chance to honor a woman who “held the door open so that many more women can do those audacious things in their own way.”

If successful, the expedition would solve one of the greatest mysteries of the 20th century and return Earhart’s Electra to the institution that helped launch her final flight. For history buffs, aviation enthusiasts, and fans of pioneering women, it is a moment when science, legacy, and human willpower meet on a remote Pacific lagoon.