Could this be the ancient rebellion that is recorded on crumbling papyri and chiseled in stone, the echo of the biblical Exodus? Many centuries have passed since one man named Moses dared to lead a people out of bondage and into inspiring equal measure of faith and skepticism. Critics have pointed, time and again, to the lack of direct archaeological proof, while believers held fast to the enduring power of the narrative.

Yet, in recent decades, the accumulation of textual, material, and cultural evidence has framed anew the debate. Egyptian inscriptions, early Hebrew poetry-even architectural parallels-all yield patterns echoing the account of Exodus. No single artifact clinches it, but taken together, such clues invite a more layered discussion about where history and religious memory meet.

What follows are the ten most interesting pieces of this puzzle, each offering a different vantage point on how ancient events might have shaped one of the most defining stories in the Bible.

1. Manetho’s Osarseph and the Exodus Parallel

The following from the Egyptian historian Manetho of the 3rd century BCE, as preserved in the writings of Josephus, describes a revolt of a priest named Osarseph against Pharaoh Amenophis. This group suffered from leprosy and joined with the Hyksos from Canaan, holding Egyptian religion in disdain, until they were forced out. Josephus expands this further to say that Osarseph took on the name Moses. As scholar Thomas Römer has shown, the fear of Pharaoh in Exodus 1.10 that there might be a joining of an internal group with external enemies constitutes the same imagined scenario as in Manetho. Though there are historic mistakes combined with polemic in Manetho’s account, strikingly similar themes of revolt, foreign alliances, and religious conflict run parallel to the biblical narrative.

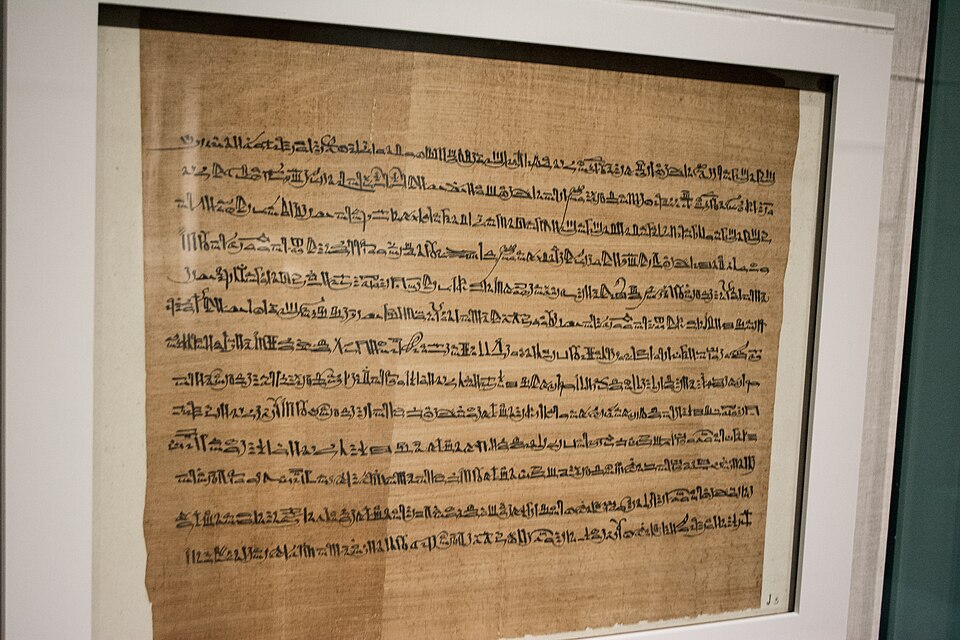

2. The Great Harris Papyrus and the ‘Haru’ Leader

The Great Harris Papyrus from the reign of Ramses III recalls chaos immediately following the death of Queen Tausert around 1188 BCE. It speaks of an “irsu” of Canaanite or Syrian origin by the name of Haru, who seized power in Egypt, abjured the Egyptian gods and then imported foreign allies. Pharaoh Setnakhte restored order, routed Haru, and exiled his followers. The pattern here of foreign-backed insurgency with attendant religious defiance and expulsion fits rather well with Exodus motifs but is certainly expressed from a distinctively Egyptian royal perspective.

3. Elephantine Monument Images of Flight

One monument from his second year, found on Elephantine Island, has the enemies fleeing “as the swallows depart before the hawk” abandoning to him gold and silver that was to be used to pay mercenaries. The image evokes Exodus 12:35–36 where Egyptians give valuables to the departing Israelites. Both accounts emphasize sudden departure under pressure, with wealth changing hands in the chaos.

4. Levites as the Exodus Core Group

Biblical scholar Richard Elliott Friedman, among others, suggests that the memory of Exodus originates not with the people of Israel as a whole but with the Levites. It is the Levites who bear Egyptian names, such as Phinehas and Hophni; they performed Egyptian rites of circumcision; and they designed the Tabernacle to resemble the battle tent of Pharaoh Rameses II. Such types of cultural fingerprints indicate an actual Egyptian origin for this group, which subsequently passed their story into the national tradition of Israel.

5. Songs of Miriam and Deborah as Historical Markers

It is the Song of Miriam, one of the oldest documents in the Bible, celebrating deliverance, without naming all of Israel. That would make some sort of sense if it had been written within a context where only Levites had been in Egypt. In contrast to this, the song of Deborah, whose actions take place in Canaan, utterly omits the tribe of Levi. Contrasts such as these suggest staggered entrances-the Levites joined the nation of Israel after the formation of the other tribes.

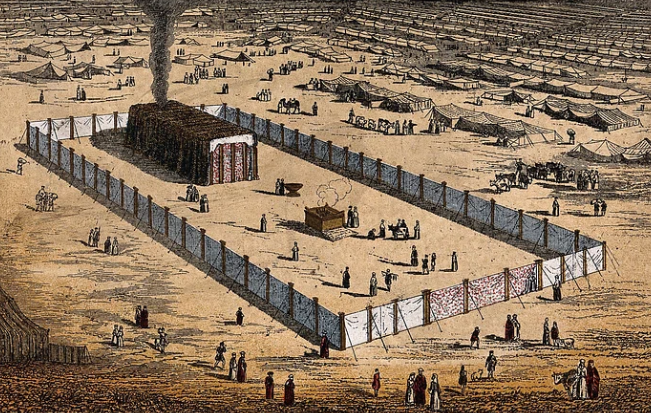

6. Egyptian Cultural Traces in Israelite Worship

Egyptian influences are reflected profoundly in Levitical sources: circumcision, fair treatment of foreigners , Tabernacle architecture modeled after Egyptian military tents. All these features are absent in the non-Levitical sources and thus represent good evidence that only a part of Israellikely the Levites-carried such customs from Egypt into the developing religion.

7. El and Yahweh United

When Levites joined the Israelite tribes, they brought worship of Yahweh into a culture venerating El as high god of Canaan. Rather than function with two gods, the communities understood El and Yahweh as one. Certain Levite-authored verses, such as Exodus 3:15 and 6:2–3, contain unmistakable evidence of this theological joining of hands that was a formative step toward Israelite monotheism.

8. Archaeological Echoes at Avaris and Pi-Ramesse

Excavations in Tell el-Dab‘a, the ancient city of Avaris, reveal a Canaanite origin settlement in the Nile Delta later overbuilt by Pi-Ramesse. Finds include the four-room house type well known from Israelite sites, and signs of sudden abandonment after Amenhotep II’s reign. These layers correspond with the biblical setting of Israelite sojourn and departure, though the site itself produced a longer history of various cultural phases.

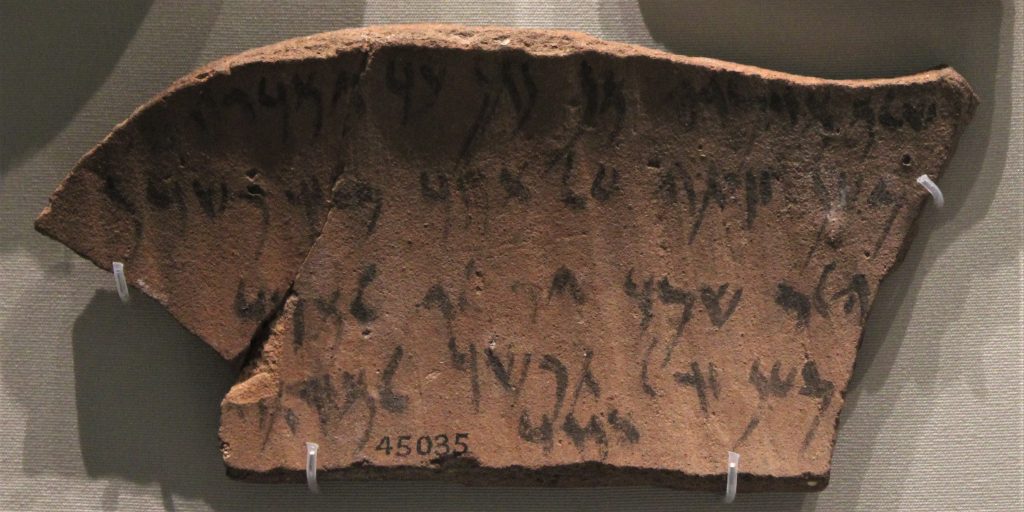

9. The Merneptah Stele and Early Israel

The earliest extra-biblical mention of Israel is found with the so-called Merneptah Stele, dated to c. 1208 BCE: “Israel is wasted, its seed is not.” Boasting of victory, it confirms Israel’s presence in Canaan by this time and supports an earlier date for the Exodus to allow time for the wilderness period and settlement before Merneptah’s campaign.

10. The Soleb Inscription and the Name of Yahweh

In a temple at Soleb built by Amenhotep III (c. 1400 BCE), a list of conquered territories includes “the land of the Shasu of Yahweh.” This is the earliest known Egyptian reference to Yahweh, locating his worship in the Canaanite region centuries before the monarchy. This discovery shows that a group dedicated to Yahweh was known to Egypt long before the biblical unification of Israel. No find of a single inscription or ruin can constitute a smoking gun for the Exodus.

But taken together, Egyptian reports of foreign-led rebellions, archaic Hebrew poetry, cultural impressions, and place-name matches make for a fascinating mosaic. To those interested in how faith and history interlink, these divergent strands of evidence will be seen to come together in a portrait that interweaves memory, theology, and lived experience within a narrative that continues to shape identity and belief today.