Why do some villains on the screen seem so irresistible–particularly when the spectator is aware that he/she is a dreadful creature? Something of the charm is craft: a performer discovers the right eyebrow-lift, the timed pause, the line-reading which makes threat a form of entertainment. Part of it is recognition, too. The stories are effective because the audience have a need to direct their nerves somewhere, and the fictional villains provide a secure distance to release said focus- an attitude commonly attributed to how comfortably people remain vigilant to danger and yet have the satisfaction of just being a part of the sequence of fictional justice a story presents.

Under these performances, there is also a history running. Hollywood had decades of circling queerness inference and coding in particular in times of limited explicit representation. That is love to hate can be bliss in a more exaggerated personality… or can be clotheslined on more ancient trifles when the prose is on the simplistic surface.

These gay, lesbian, transgender, and queer performers are on the thrilling side of that divide: they make audiences gasp, laugh, recoil, and quote them nevertheless.

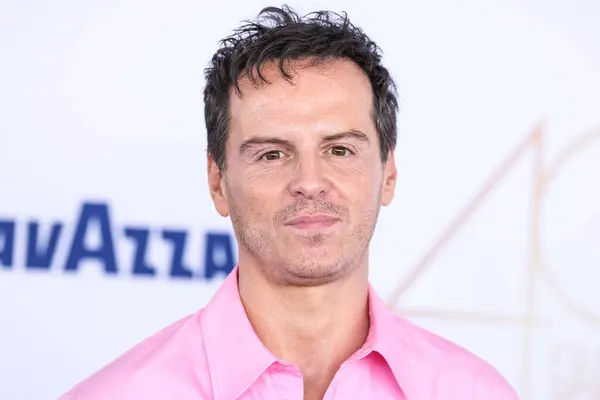

1. Andrew Scott

Andrew Scott, as a villain in Sherlock, portrayed as Jim Moriarty, transformed a stereotypical villain into a live wire – delightful one moment, dreadful the next. It is known as an emotional rollercoaster because Scott switches between control and an outburst of emotions and does not lose control of the situation. The staying power of the role is also due to the fact that the show did not regard Moriarty as a challenge, but as an event: the character gradually haunts even after he has disappeared, and the audience reaction was even a part of the fun. Scott himself once explained his career intention in his typical succinct way: To play as many different notes as you could.

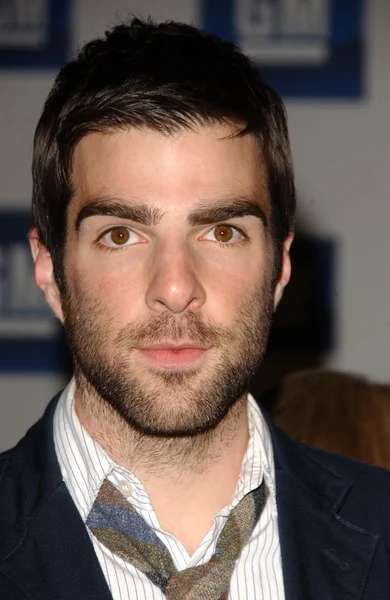

2. Zachary Quinto

The character of Zachary Quinto, Sylar, on Heroes is still a prototype of the modern television predator: silent, observant, hideously patient. The villainous Quinto makes land with what is known as restraint by menace expressed in quietness and micro-expression like everything could really be violent. Even in cases where he becomes more controlled, and often more emotionally detached Spock in Star Trek, the same precision becomes threatening in other circumstances. It turns out to be a performer whom the audience can rely on to make intellect dangerous.

3. Ian McKellen

The reason why Ian McKellen makes a good Magneto in X-Men is that he does not take the part as one of the cartoons. He portrays Magneto as a righteous, hurt and tactical, a person who can make a refined case and plot something disastrous. It is that balance which makes the viewer argue with himself as he watches: the character is in the wrong, and yet the belief is compelling. When McKellen is making overtly villainous elsewhere, the trick remains the same–humanity first, show second.

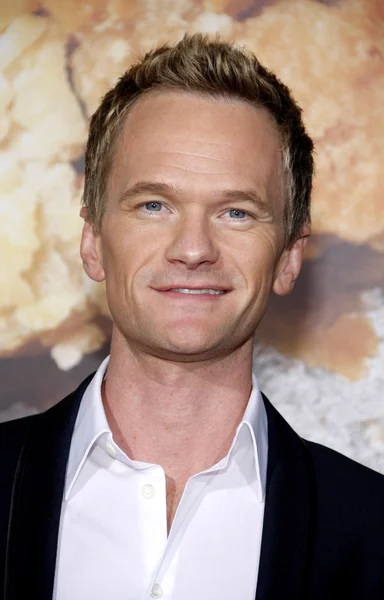

4. Neil Patrick Harris

Count Olaf by Neil Patrick Harris in A Series of Unfortunate Events is an acting masterpiece of villainy. Heavy makeup and broad humor might have smoothed the character to the level of noise, but Harris applies timing gained on the stage to make the selfishness of Olaf not a generic one. The savagery is embodied but the play asks the people to appreciate the ridiculousness of the dedication. It is the type of villain who causes the viewers to laugh and then feel guilty about laughing.

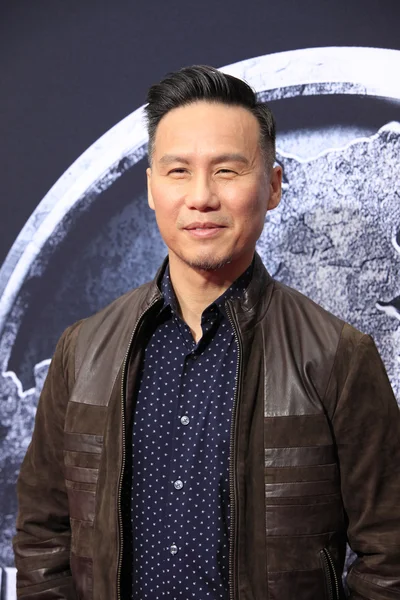

5. BD Wong

The character of Dr. Henry Wu played by BD Wong throughout the Jurassic World period represents an alternative screen threat in the form of the professional demeanor that never raises his voice. The fact that Wu develops into a colder character is a weakness since Wong tries to play intelligence as certainty; a belief that has no second side and, therefore, the work is more important than the consequences. The coldness of the character is not dramatic but business and medical, the type of villainy that makes sense until after it is too late.

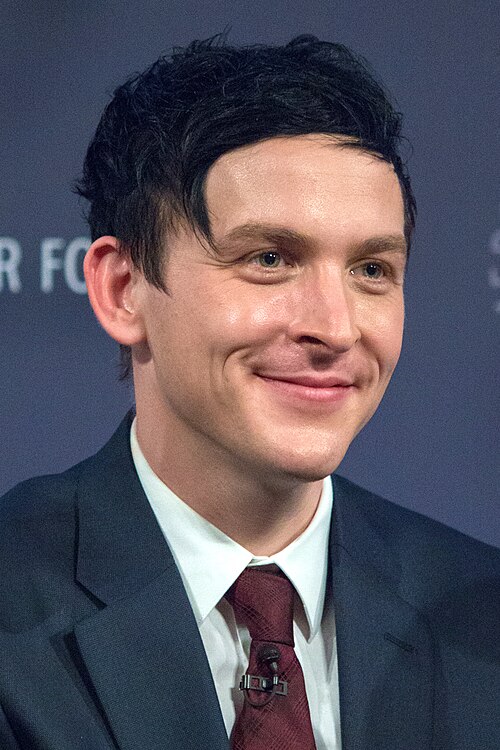

6. Robin Lord Taylor

In Gotham, Oswald Cobblepot (Penguin) played by Robin Lord Taylor is addictive since the lack of vulnerability is the source of violence. He is desperate to be seen, desperate to be safe, and desperate to be powerful– and needs collide in the eyes of people. Taylor makes ambition of the character an open nerve; the viewer shivers, followed by a closer approach. It is that irony of sympathy mixed with fear that makes the label of love to hate so sticky.

7. Alan Cumming

Perhaps the most famous portrayal of humor enhancing the villain rather than making him cuddly is Alan Cumming as Boris Grishenko in GoldenEye. The hubris, the celebration, the satisfied reliance on the self,–Cumming has played his charisma out till it turns vulgar, and then, once more, to the humorous. He is also a reminder of a larger tradition: flamboyance has always been employed to represent antagonism as a visual shorthand, a convention framed by the established rules of older media such as the Hays Code and encoded characterization.

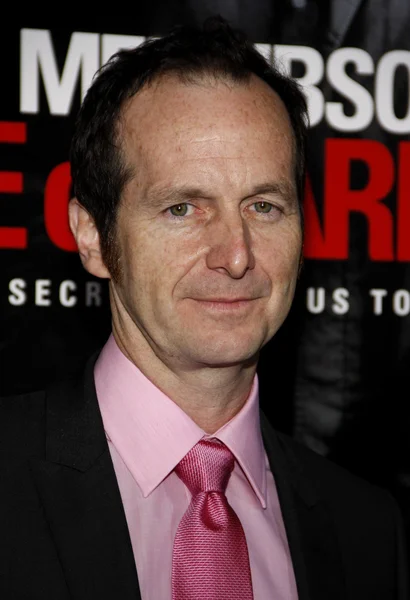

8. Denis O’Hare

Denis O’Hare is a star of heightened worlds (American Horror Story True Blood) due to his ability to induce melodrama into feeling disciplined. His villains are not merely ill mannered but they are doing their mayhem, and they often do it in a manner that provokes the audience to turn their back. The influence is magnetic even in case the character is monstrous. It does not justify the behavior to viewers, they cannot help but watch it when the actor sets it in motion.

9. Jim Parsons

Sheldon Cooper, the character played by Jim Parsons, is not a villain, but often the impediment, hard, self-absorbed, and tiresome in a manner that seems too close to the truth. Parsons makes that friction amusing by making certainty a comedy: Sheldon really believes that he is right and the show allows the audience to enjoy the collision between his reasoning and the patience of other people. That is love to hate with no capes, no crimes or no evil schemes, just a character that is so obstinate that it irritates itself and becomes part of the viewing experience.

10. Dan Levy

The character of David Rose played by Dan Levy in Schitts creek starts as a walking wince: opinionated, sensitive to all things, and not afraid to show his disgust at being inconvenienced. One admires the performance because Levy makes the snark a defense instead of a sadism – self-defense in the shape of a single line. As David becomes older, the character retains the pointed edges that made him amusing, yet here the audience sees what they are harnessed to: style, particularity and an anxiety that is no longer kept under wraps.

These performances are united not by one type of villain. It is manipulation: the possibility to make the audience uncomfortable and turn it into entertainment without losing the reality of the character.

And in an industry where performers have reported ongoing barriers such as 53% of LGBT respondents believed that directors and producers are biased against LGBT performers in hiring the range on display here matters. These actors are not just playing characters audiences love to hate; they are expanding what audiences expect to see.