“Few artifacts have been so widely traveled without budging an inch. The Ark of the Covenant, ‘a gold-covered wooden box constructed to house the stone tablets of the Ten Commandments,’ occupies a zone of faith, memory, and archaeology where truth is seldom allowed to endure.”

In the biblical tradition, the Ark is never just luggage. It is hidden, transported with ritual care, and functions as a boundary marker between the world of everyday life and the world of dangerous holiness. This explains, in part, why the Ark narrative has a tendency to recur in new locations and for new purposes. The following is not a search for a single box, but rather an understanding of the ideas that cluster around it.

1. The Ark’s blueprint reads like ritual engineering

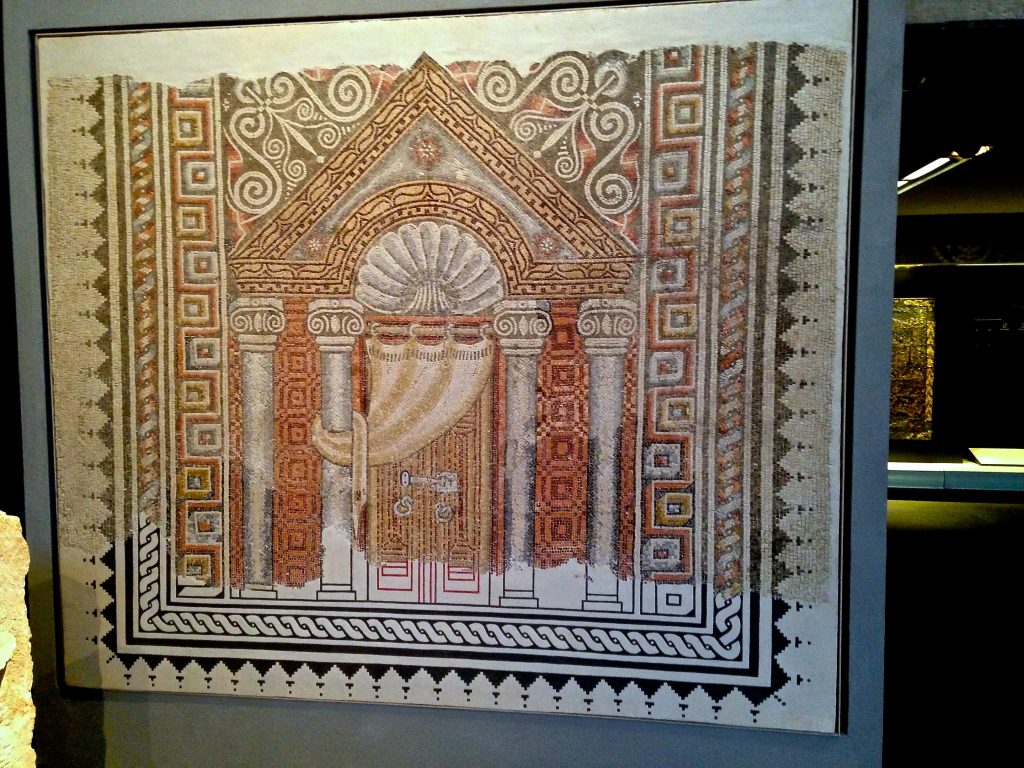

The description of the Ark in Exodus is remarkably detailed: a box of acacia wood, overlaid with gold, made for carrying with the use of rings and poles. The reference traditions provide a more extensive list of contents: tablets, manna, and Aaron’s rod, so that the Ark becomes a mobile repository of identity, rather than a simple container. The most fascinating remnant of the original that has attracted so much later interpretation is the cover as a place of meeting, associated with the term “mercy seat,” where the divine presence was thought to reside between the cherubim. The power of the Ark, in this formulation, lies in the regulations of access, not in public display.

2. The Ark’s journey is also the route of the holy sites of early Israel

The biblical stories move the Ark of God through a series of locations that will become the foundation of religious memory: the crossing of the Jordan River, the city of Jericho, and then its guardianship at places like Shiloh, before the conflict with the Philistines. The story constantly weaves the Ark with points of crisis: crossing rivers, breaching walls, loss, and difficult returns. Even in those instances where the narrative tells of celebration, as in King David’s parade to Jerusalem, the Ark is always potentially explosive: the curiosity about its contents is always dangerous. These events are more than the dramatization of religious belief; they form the basis of a transportable legitimacy that can be taken, seized, hidden, or moved along with political power.

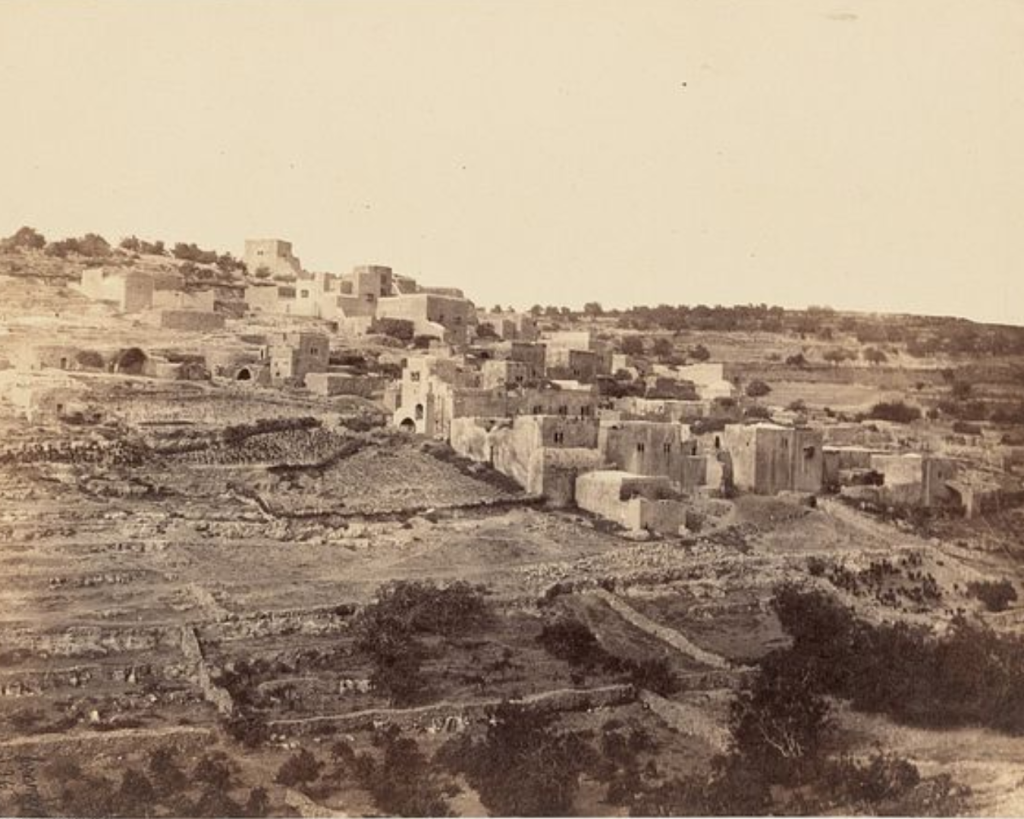

3. A significant archaeological discovery reinterprets Kiriath-Jearim as a political platform

At Kiriath-Jearim, an Iron Age raised platform was discovered that was estimated to be 150-110 meters in size, indicating a monumental administrative or cultic complex rather than a small shrine in a rural area. Israel Finkelstein has described the excavation as shedding light on “the power of Israel (the Northern Kingdom) in the early 8th century”, and the excavation team approached the traditions of the Ark as stories that could be used in statecraft. Whether or not the Ark was a real object, the environment in which the story of the Ark took place can still make stone footprints.

4. The Ark vanishes from historical records and this absence of information is significant

After the Temple of Solomon becomes the legendary final resting place of the Ark in the Holy of Holies, the biblical narrative draws closer to disaster: the conquest of Jerusalem and the destruction of the temple in the sixth century BCE, and the absence of the Ark. Later versions diverge rather than meet. Some versions assign its hiding to a forward-thinking King Josiah, while another version, as recorded in 2 Maccabees, assigns it to Jeremiah. Even in versions of Roman loot, other treasures of the temple are listed, but not the Ark, supporting an earlier disappearance. The silence has been like an open invitation: once an item goes missing from the inventory, it becomes available to every new geography that wants it.

5. Ethiopia preserves the Ark story in architecture and custodianship

In Ethiopia, the Ark is maintained more as an ongoing practice than as an anecdote. Churches are constructed around a Holy of Holies where a copy of the tabot is placed, reflecting the Jerusalem Temple’s rationality of limited access. The practice is centered in Aksum at the Church of Mary of Zion, where only a lifetime caretaker is believed to have access to the object. However, a contradictory voice is that of the Ethiopiologist Edward Ullendorff, who remembered being able to inspect the object in Aksum in 1941 and later stated, “I’ve seen it.” In his version, it was a medieval wooden chest and empty. The conflict between holiness and material authenticity is part of what makes the claim culturally powerful.

6. Southern Africa’s Ngoma Lungundu demonstrates how Ark-like artifacts can be genuine without being “the Ark”

The Lemba of Zimbabwe have the Ngoma Lungundu, or “the drum that thunders,” which is a sacred carried object with its own lineage. It is located in the Zimbabwe Museum of Human Sciences and has been called the oldest wooden artifact discovered in sub-Saharan Africa. The Lemba tradition of the object is its connection to the Ark as a copy made from what was left of the original, and its use as a carried symbol of protection is similar to the Ark’s status in the Bible. In addition to the object itself, studies on Lemba genealogy introduced another level of interest: a 2000 study found that some Lemba, particularly from the Buba clan, possess the Cohen Modal Haplotype, a genetic marker found in Jewish priests.

7. Europe’s “Ark sightings” illustrate how the presence of relics can be used to support institutional power

Medieval Europe had its own paths of Ark trajectories Chartres, Rome, and others that were not archaeology but rather claims of spiritual heritage. In Rome, there was a tradition that the Lateran Basilica had an Ark for several centuries, displayed with other holy objects, until Pope Benedict XIV decided to remove it from public display in 1745, after viewing a decorated chest covered in silk. A contemporary academic study traced this tradition to the post-Crusade debates over continuity with the temple traditions of Jerusalem, where the Ark was seen less as an artifact transferred than as a badge of honor: whoever “possessed” the Ark could claim to possess spiritual authority itself.

The history of the Ark’s afterlife is thus one of institutions vying to center meaning. The Ark of the Covenant continues to exist because it functions like a compass, pointing different communities towards their own ‘origin stories’ of law, presence, protection, and legitimacy, without necessarily needing a universal consensus on where and what the Ark is. Ultimately, the Ark’s most lasting location may be the human need to locate the sacred in a definite place, even when history fails to cooperate.