One of these was Wyatt Earp, who once broke the most notorious frontier talent down to a very prosaic art: Whoever was the most successful gunman, was the man who was slowest. The line cuts through the home-stage image of high-noon theatrics, and it is put in its place by something much nearer to lived reality, hesitation, calculation, the heavy hand of reputation.

The West during the period of the late nineteenth century created individuals who were characterised earlier than history. These were distorted by sensational newspaper publishers; others were stretched out on one sheet- one duel, one ambuscade, one trial, one court scene- till their lives had become the evidence of a legend.

These eight characters survive not due to their clean stories, but despite it. Their survivance, their inconsistencies, and their afterlives in the popular culture demonstrate how easily a frontier could make a person a symbol, and how difficult it is to make a symbol a person again.

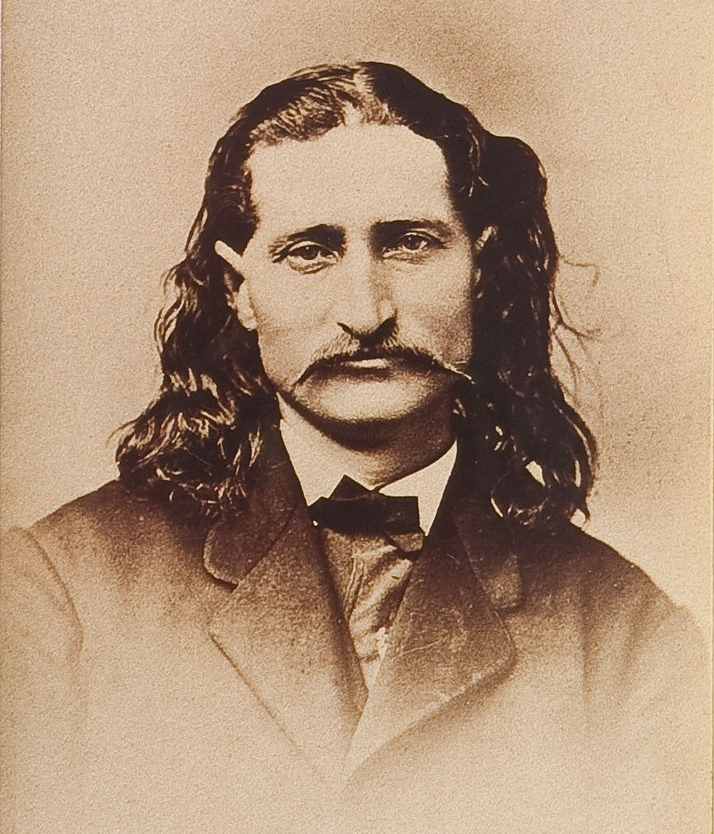

1. Wild Bill Hickok

The character of Hickok is based on an episode that can be read like the blueprint of everything that came after: a confrontation on the street in Springfield, Missouri, in 1865. The distance is set at around 75 yards, a distance that focuses more on aiming than fluidity, and contributes to the reason why the episode became a unique duel which could be repackaged and resold by the storytellers later. The quarrel itself an obligation of dice and a watch has long been retold as western melodrama, but even more effective material is the most basic: Hickok pulled himself up and fired with intent.

What became mythified was not necessarily initiated as such. The proceedings of the court and a coroner’s report that were thought lost were subsequently rediscovered by local researchers and helped further to isolate what had been said and what had been subsequently told and remembered. The acquittal of Hickok, and the rapidity with which his name spread, afterwards demonstrate the other expediency of the West, publicity.

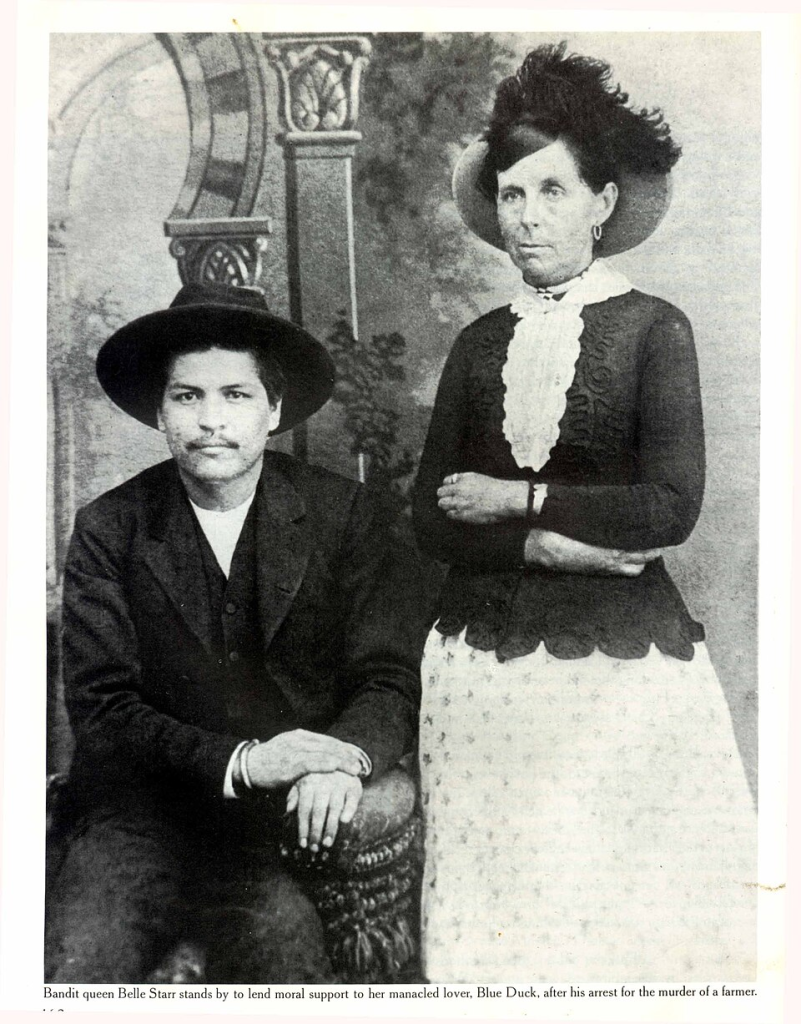

2. Belle Starr

The fame of Starr explains how a murder might turn into a myth of creation. She was killed in 1889 outside her house in Oklahoma, and the murderer is never brought to a definitive conclusion of identity, providing a vacuum that subsequently was gladly occupied by story tellers. Her appearance, black velvet, plumed hat, was to be used shorthandedly as sign of danger and defiance, as though costume would take the place of biography.

Her legend grew since it was something that distant readers desired of the frontier: salacious drama that was exotic and consumable. A little bulletin might be worked up into a national stomach and a bandit queen be formed out of half-truths and noisy publicity. The outcome was a figure who in one sense is abnormally contemporary: the public figure, in fact, occasionally came earlier, and lingered longer than the record which could be verified.

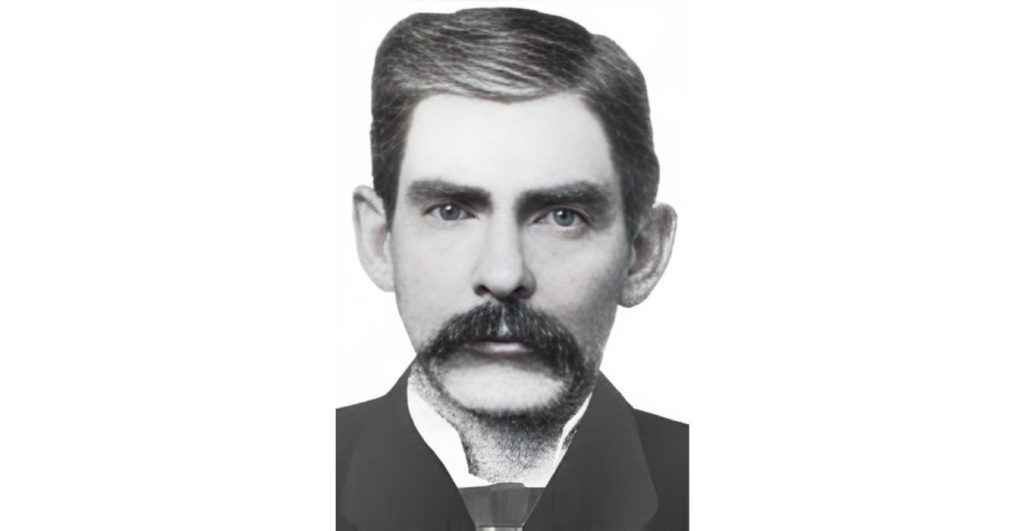

3. Doc Holliday

The novel by Holliday defies one genre. A dentist Amateurishly trained, and beaten west by tuberculosis, he drifted through the saloons and gambling tables as though he were spending his borrowed time. After his death, it was reported that this man never resembled a stock villain “weak,” “scrupulously neat,” not without a childlike air but with a reputation of deadly violence. The conflict between looks and fear contributed to his name retention.

At Tombstone he could not be separated with the Earp circle, and the gun battle near the O.K. Corral attached him to the commemoration of popular memory. The focus of contemporary description lies on the fact that the situation exploded incredibly fast and that it was hardly resembling a duel where a large crowd was witnessing. More than thirty shots were reported to have burst out in a clumped-up explosion. The lasting contribution of Holliday is not to the gunfighters so popular in the West, but to the fact that they were often ill, mobile, and precariously used.

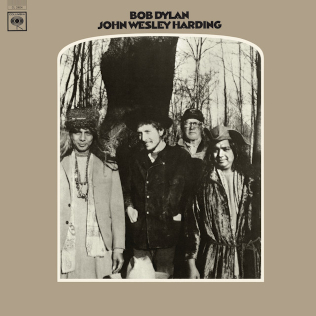

4. John Wesley Hardin

The life of Hardin is a struggle of self-portrait versus evidence. He said there had been an enormous body count -more than 40, by his own count and historians often come closer to a figure of 20, which is significant since it demonstrates how reputation could be nurtured like money. He grew up in the Methodist ministry, and he had a tendency toward deadly increment of argument that in more filter areas would have resulted in bruises and bitterness.

Jailing, jurisprudence, and a late bid at respectability could not remove the accrued peril in his name. His demise shot in the back of the head in an El Paso saloon was reminiscent of a western style where conclusions were usually delivered by the rear, rather than in a sunlit street.

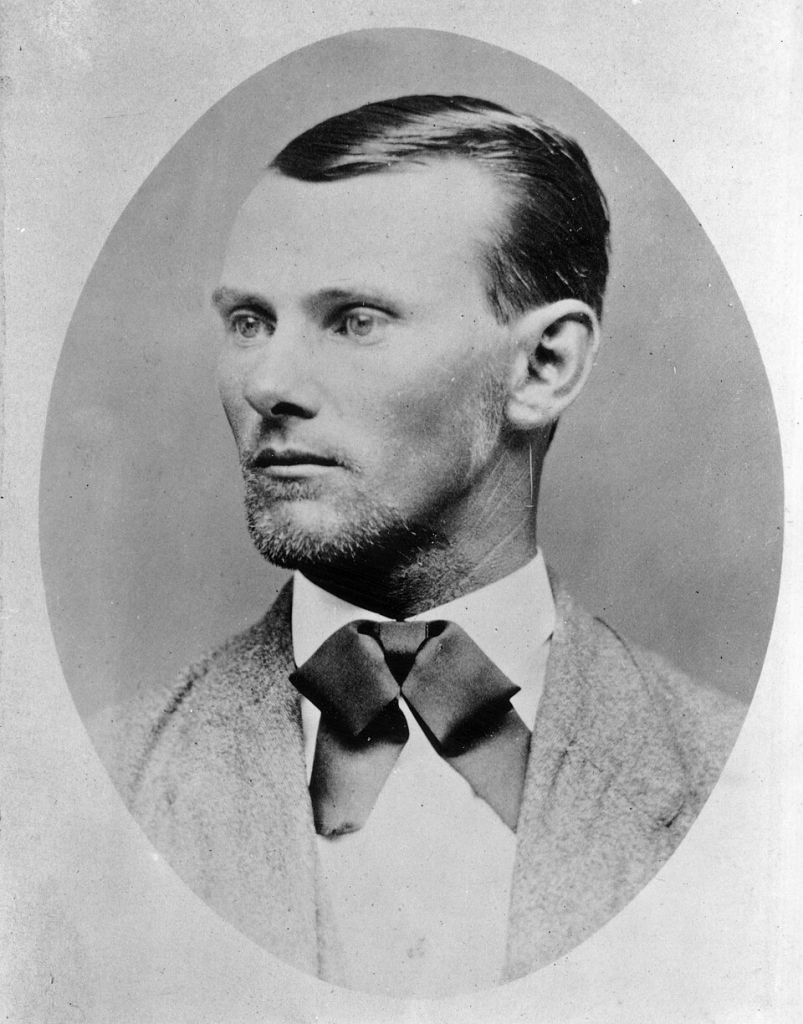

5. Jesse James

James was a national paradox: he was a criminal in reality and folk hero in fiction. The bank and train robberies of his gang after the Civil War provided it with the raw material, which could then be interpreted by sympathetic mythmakers as rebellion, not theft. Even where the math failed, the tint of the version of Robin Hood remained.

His death was not a fight but a treachery. James left the world shot in the back by a member of his own circle, Robert Ford, and this left the weakness behind the legend exposed. It also showed how celebrity could transform even an outlaw into something of value not only when alive as a threat, but when dead as a story.

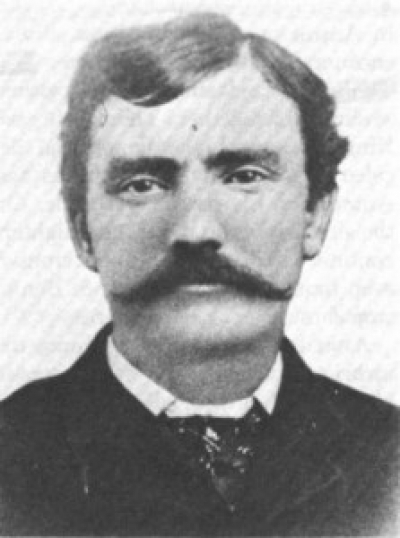

6. King Fisher

The beauty of the frontier is in its ethical two-sidedness that Fisher appeals to. He dressed gaudily, walked with panache, and at various times was able to be at once outlaw and lawman, a sort of social agility, which succeeded best where the institutions were very thin and the personal insistence was very strong. Accounts of his gun fights differ in motive self-defense in one version, cold calculation in others, but the greater fact is: charm may also coexist with brutality without causing that much cognitive dissonance in the communities which observed him.

He was killed in an ambush in 1884 in San Antonio and this sublime finale strengthens how many times violence in the West worked as logistics instead of spectacle.

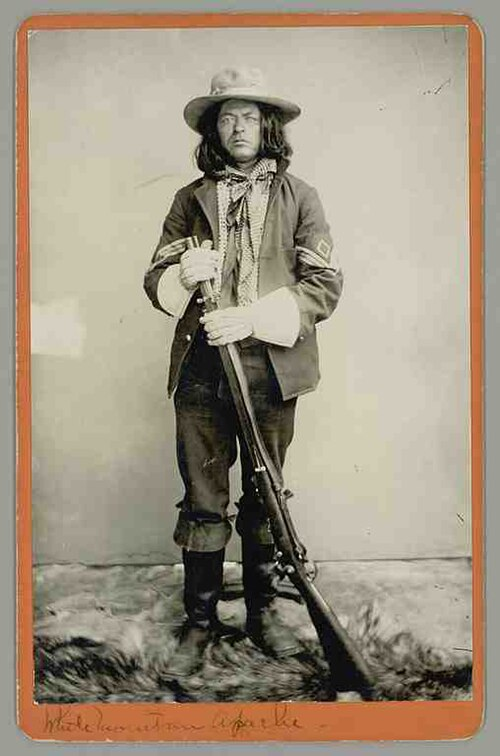

7. Billy the Kid

The life of Billy the Kid and his afterlife can be equally disclosing. Young and dragged into the world by crime, he was indissoluble with the Lincoln County War, and afterwards with the legend of youthful chutz. The conventional assertion that he murdered 21 men was continued, not because it was easy to establish, but because it was so memorable.

Even his death could not remain calm. One of the most quoted stories is that he was in Fort Sumner, late one night, as he entered the home of Pete Maxwell and, moving forward into a dark room, Pat Garrett shot him first. In his version, Garrett, a moment later, had been left in suspense at a slight hesitation Billy within a foot of Garrett’s chest, and his pistol in his grasp when two shots killed him. However, it was fueled by legends later when men were arguing that they were Billy the Kid for decades proving that attractive identity does not die because of unpleasant name.

8. Tom Horn

The name of Horn is still soldered to the most ugly query of the West, What happens when violence is a service. He served as a scout and tracker, and later as a range enforcer in the cattle wars of the 1890s, where the cattle ranchers could afford a gun, much like they could afford fencing wire. He was found guilty of the murder of 14 year old Willie Nickell and the case remained controversial due to the fact it had all the elements that make a public argument enduring, that is, the confession, the retraction and the competing motives.

One of the lines credited to him prior to trial continues to serve as an act of self authoring: In the event of my murder now I shall have the pleasure of thinking I have led some 15 common lives. It may be interpreted as bravado, or as fatigue, whatever the case, it suits a man whose autobiography, it is observed by supporters, must be handled with care as a source as well. The interest that Horn expresses in continuing to study his subject is based upon the fact that his narrative is explicitly connected to frontier violence in terms of employment and power, rather than individual settlements.

The duel, however, is not the most relentless trend in these lives but the narrative aftermath; rumors, biographies, court records and eyewitness accounts that over and over again are altering what the masses believed to be known. The Wild West is interesting as it created as much danger as it created stories, and because, between the two, human beings continued to be lost in focus at an industrial rate.