What then does home look like to someone who hardly ever kept still? The visits of Marilyn Monroe shifted regularly, hotels, borrowed guest suites, rented houses, and, lastly, a small home that she had made herself. But the more intimate narrative lies in smaller and less noisy signposts: the books piled around her, the seclusion which she ensured, the familiar rooms transformed into a studio, and the habits to which she resorted when the general clatter had died away.

These are the facts that follow a household existence more transportable than permanent, more about convenience than permanence, and the few things and ways that moved easily.

1. A piano she searched for like a lost family heirloom

In her autobiography, Monroe wrote about how she had located a second-hand grand piano that she had used as a child- one thing she had associated with the first sense of permanence. Years later as I was making a living in some money as a model she wrote in My Story that she began to seek the Fredric March piano. I had spotted it in a mothy auction room after some twelve months and purchased it. I now have it in my home in Hollywood…and [it] sounds as good as any piano anywhere in the world.

2. A hotel suite that functioned as a private front door

Monroe was able to appear to live alone even when her life was intertwined with the lives of other people. She described in a biography her apartment, a one-bedroom suite with a kitchenette in the Beverly Carlton Hotel, in order to have her mails delivered and to have a feeling of autonomy on paper but to be surrounded by books and reproductions of works of art, which indicated a serious self-directed taste.

3. A dressing room that doubled as a practice room

Monroe used her work areas as training fields. She wrote that the early money was spent on lessons, dramatic, dance and singing, and that she used to buy books and read from scripts in front of a mirror well into the night. In My Story, she wrote that she fell in love with her own self not the person she was, but the person she was to become, and found her own home in a secret practice of the life she was to lead.

4. A blunt boundary around the ordinary details of her rooms

The only design principle that was true to Monroe in his domestic life was discretion. I do not want all of you to know the exact location of my house and what my couch or my fire place would look like, she said. “Do you know the book Everyman? Well, I would like to remain only in the fantasy of Everyman. The declaration comes out as a roadmap of how she has distanced the icon and the person.

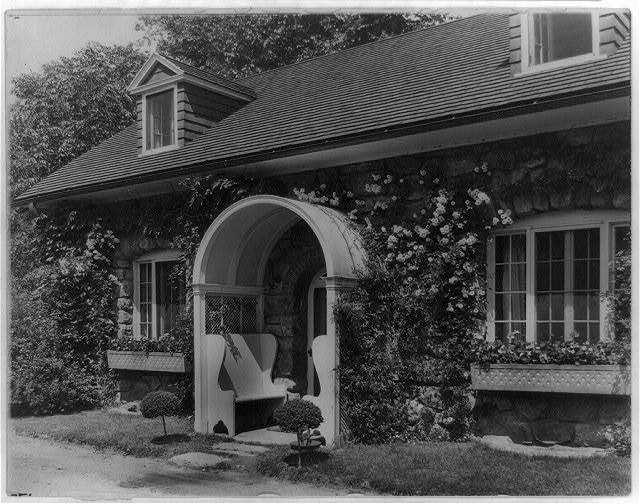

5. A Connecticut guest suite that felt like “safe harbor”

During some period, Monroe moved in with photographer Milton H. Greene and his wife in Connecticut where she was treated as a family and not a spectacle. It was afterwards recorded by Greene himself son: If you were famous, you were safe in the Greene family, Joshua Greene said to me. The house provided her some sense of freedom and isolation.

6. A dinner routine that was almost aggressively simple

In her cottages Monroe wrote of meals in the prosaic style of a woman who feeds herself in between long days. In 1952, she shocked a fashion magazine with her dinners at home which were startlingly simple. I go to the market by my hotel each night, and get a steak, or some of the lamb chops, or some liver…. With my meat I generally consume the four or five raw carrots, and that is all. The description also is a less diet-like perception and rather like a technique: few choices, untroubled gasoline, well-known dominance.

7. Sleep as a ritual, not an afterthought

Her leisure time was particular and even defensive. In the same 1952 interview, Monroe wrote about mornings that were slow, of waking long, and a sleeping arrangement that was conducive: an extra-wide single bed, one heavy down comforter in all seasons, and dislike of pajamas. The details hint that rest, which is so rare in her time, was made a fetish.

8. A rejected Frank Lloyd Wright dream that still revealed what she wanted

At least one house design by Frank Lloyd Wright was reportedly on his list of new homes he had planned to be built at Roxbury, Connecticut, by Monroe and Arthur Miller. A subsequent version of the unrealized scheme was of a dramatic circular living room, with skylights and huge columns of fieldstone, which commanded a 70-foot swimming pool. The project was not pursued but it highlighted a familiar conflict of her domestic life, a need to be sheltered and simple and a need to be beautiful with an irresistible muscle.

9. A final Spanish Colonial house that became part landmark, part confession

Not celebrity alone has marked Monroe out as the last home of his in Brentwood, his 1929 Spanish Colonial Revival. It became her only property that she owned without a mortgage and preservationists have stressed its importance in an era when only 0.1 per cent of young women living alone were house owners. The house was also famous because of a threshold plaque that was written as Cursum Perficio (My Journey Ends Here) and because of personal decisions that continue to resonate in the building, such as the Mexican tiles she chose, a garden that she worked, and rooms that were designed around the idea of privacy, not performance.

The fact that the home is still known as a preserved Historic-Cultural Monument is also identified as working in a broader initiative to redress the lack of women in the number of such designations. Home in Monroe is not something that can be said to be found at any particular address, but a set of comforts that can be replicated: music, studying, sleeping, a garden, the right to shut the door. Ultimately, it is the domestic details that survive exactly due to the fact that they were not created to be read by an audience.