There can be few other moral terms that have circulated so much or have been as long enduring as the seven deadly sins. They are not, in Christian doctrine, single sins in themselves, but modes of being, which may produce other injuries, both personal and social, by inclining desire, judgment, and attention to foreseeable inclinations.

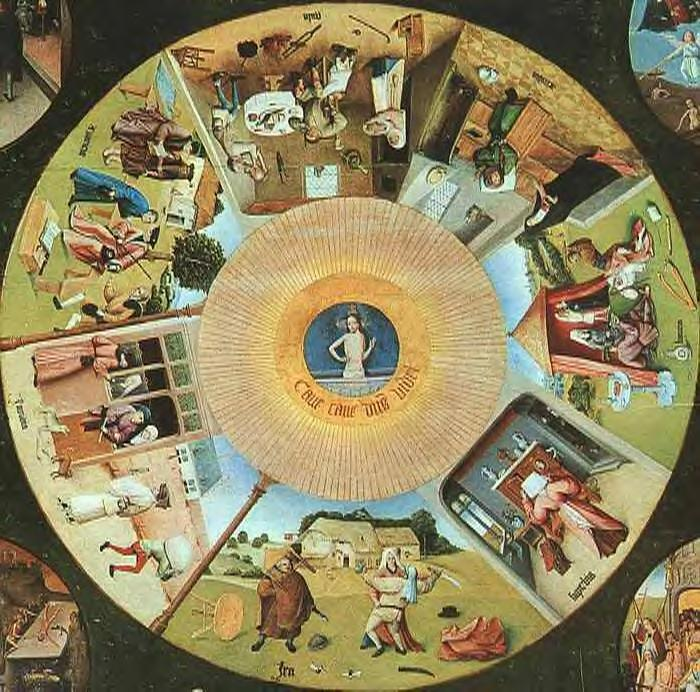

It was a tradition which shaped itself through centuries: a monastic catalogue of vices of Evagrius Ponticus, a more stable scheme of vices of Gregory the Great and subsequent improvements by Thomas Aquinas. It was a list that survived both because it made available a handily navigable map of inner life, and because artists and writers again and again rendered the vices discernible in the mundane scenes making theology something the eye could see.

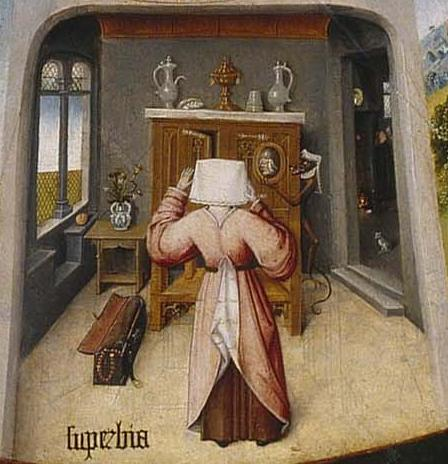

1. Pride

In the traditional theological context, pride is an extreme friendship to the own virtue that disrupts the thankfulness chain. Rather than receiving the gifts, assistance, and boundaries, an individual attributes all the significance of success to the self and considers dependence as disgrace. Medieval authors frequently used pride as a unifying vice, as it may masquerade as a virtue, such as industry without humility, confidence without reality testing, conviction without teachability. As we will see later, a related vice is at times also known as vainglory, the craving of praise; it also is not identical to pride but one which focuses on the approval of the masses rather than self reward.

2. Greed

Greed (or avarice) is an unreasonable love of money or property, even though honors and status were also not excluded by older moral analysis as an object of the same appetite. It is significant to that larger definition because in a culture where social position is sought as bitterly as money. In traditional narratives, greed reduces the scope of attention: relations turn into transactions, time turns into an accountant, and enough turns out to be hard to discern. One of the reasons the vice has always appeared constant in the lists of various historical periods is because of it.

3. Envy

Envy is sadness at the good of the other, and more acutely, the feeling that the prosperity of the other takes away the good of the other. Gregory the great defined envy, generating exultation at the misfortunes of a neighbour, and affliction at his prosperity a very concise definition, but nevertheless containing the emotional twist. Previous catalogues occasionally united envy with sadness, as the emotion frequently comes as a form of grief: not grief at having been deprived of something, but the grief that someone else has acquired. The vice thrives where living is a comparison and not a vocation and this has transformed the other people into measurements and not neighbors.

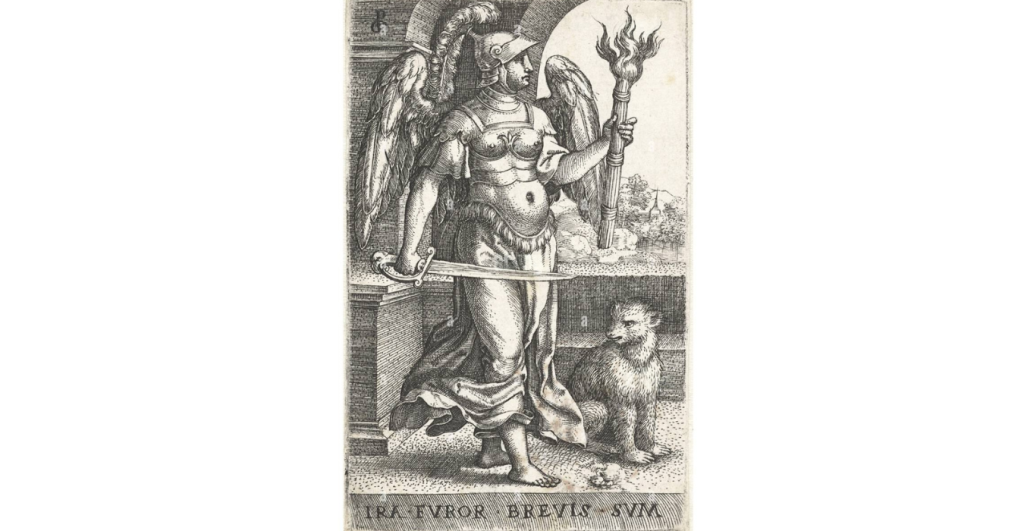

4. Wrath

Wrath is not the same as anger. The proportionate and reasonable anger may be the response which allows naming injustice. Anger contributes a wish to suffer evil a wish to punish, which makes the misery of a fellow man a medicine to its own. The formulation of the Catechism puts the boundary to a willful intention to kill or to maim seriously a neighbor and that intention is considered a serious breach of charity. Wrath in moral art is frequently represented by scenes of struggle since the vice wants to get out of control; it is a motor turning grievance into identity.

5. Sloth

Sloth is often confused with the mere lazy behavior but classical theology regarded it as something more: a sinful refusal to labor: a spiritual or moral indifference which leads to the disposition to goodness. Aquinas even called sloth as a form of sadness which causes a person to be slow in spiritual exercises. That connection can be used to understand why sloth can also be present together with busyness; distractions can serve as an avoidance and not a rest. In a famous visual illustration, the Table of the Seven Deadly Sins by Bosch puts normal people around an observer Christ, indicating that the sin can be disguised as normal and slowly suck out the essence.

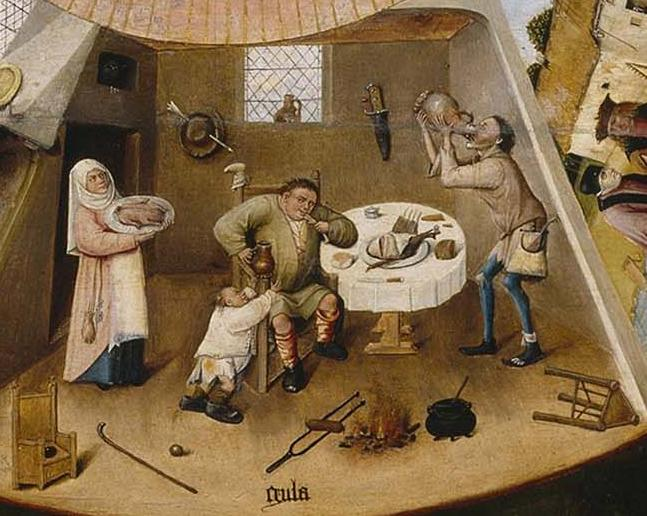

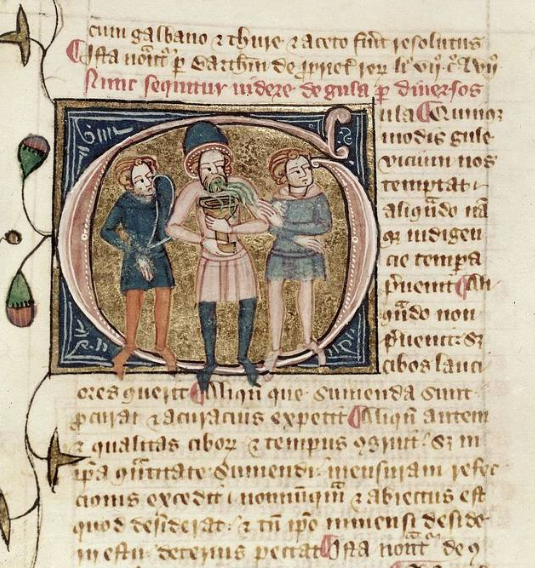

6. Gluttony

Gluttony refers to excessive consumption of food and beverage which contains drunkenness, which is not restricted to quantity. It takes appetite as power and pleasure as rights, cut off the head by reason, gratitude and body and community care.

Gluttony is a common vice in historical moral painting, as part of the comic disorder of food, drink, and sensuality overflowing into negligence, since the vice rarely remains within itself. It does not mean that pleasure is a bad thing, but that excessive appetite is a rule of some sort.

7. Lust

The disordered desire of sexual pleasure when pleasure is sought in isolation of its unitive and procreative functions is lust in the Catholic moral teaching. The vice is comprehensive: it is not just a matter of actions but also of customs of mind that objectify persons. There has been a significant shift in the attitudes of the population in regard to sexual ethics, but the previous analysis still presents a familiar pattern of moral dynamics the erosion of intimacy to consumption. Lust is frequently combined with collateral vices in literature and art, as secret, treachery, and conflict are likely to cluster around the desire in desire that does not respect moral boundaries.

The seven deadly sins endure since they are used to explain recurring trends other than the scandals experienced during a particular period. They call names to methods of attention being misdirected: toward self instead of gift, possession instead of sufficiency, comparison instead of communion, vengeance instead of repair, distraction instead of devotion, appetite instead of measure, and pleasure instead of personhood. Through centuries of theologies and arts, the ancient statement has stood unchanged, repetition that which is internal is external, and the most minute habits, without attention, educate the heart on what to love.