Archeology is not putting new chapters to the Scripture, but it alters the modes of hearing the old ones. A piece of papyrus, an inscription of boasting enemies, a water-tunnel to keep cool on the skin these are not to replace reading. The reminders are that biblical faith had to be nourished on common soil: ink, stone, drought, trade, and political persecution.

The bible may appear to many readers as a closed room: sacred, significant, and so foreign. The material evidence itself cannot produce the belief, but it can lead to the reduction of the time lag between then and now, demonstrating the feel of the world which created the text.

These are guides to the common reader who desires that his or her interaction with Scripture does not merely stay on the surface, but remains localized, without descending into an exercise of trivia.

1. One little piece of Gospel that might have been overlooked, that might have been early

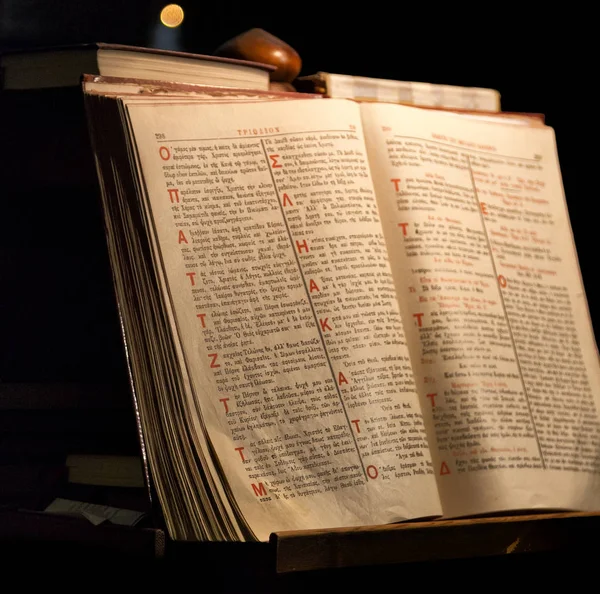

One well-known Papyrus, the Rylands Library Papyrus P52 is known by its size: a small fragment of the John Gospel. What is significant about it is what it silently confirms, that early Christians copied, circulated and stored the traditions of Jesus near the time when those traditional memories were being challenged and could be very expensive. To the reader who has been conditioned to think of the New Testament as the work of a creation that occurred many centuries after the fallacy of legend, such an artifact provides a different emotional appeal; Scripture as the work of handled text, as opposed to floating idea.

So much as there is a photograph of such a fragment, but it does something pastoral. It renders the Bible not so much a modern thing that just theorizes about the past, but an ancient thing that has passed through time.

2. A monument of an enemy still calling the House of David

The question of whether David is part of the past or merely a legend has been one of the most debated ones in the study of bibles. In an Aramaic victory stele, also found in 1993 in Tel Dan in northern Israel, the phrase king of the House of David appears. The reason as to why the line is relevant is that the line is not a devotional line; it is a by-product of an opposing power. David is recollected even in aggression as a fact of a dynasty worthy of naming.

This leaves all arguments as to the extent of the kingdom of David unsettled. It does, though, peg messianic language on the stark reality that Judah leader-ship was perceived as part of an identifiable line.

3. A pool and a tunnel making a place where a miracle takes place walkable

The Gospels are now located in the stratified history of engineering in Jerusalem through Hezekiah Tunnel and the Pool of Siloam. The stroll along the path leads the body into the channel of survival instincts in the city: the water guarded with weaponry, the stone cut to persist, the geography forming the belief.

When John writes about the blind man being sent by Jesus to wash at Siloam, the passage is differently read as soon as the place is no longer imaginary space but a terminus of an ancient infrastructure. Archaeology is that which does not explain a miracle away; it makes clear the level on which the meaning was acted on.

4. Newly released dam wall that re-presents Siloam as climate problem solving

Recent excavation findings gave an unexpected twist to the story of Siloam: a grand dam wall connected with the pool system, an exposed portion of which was reported as 69 feet (21 meters) and an approximate original height as 40 feet (12 meters). Carbon-14 datings put the date of construction at 805795 BC. Simply put, the pool area was not just a setting to subsequent Gospel memory, but also a civic reaction to volatility of water.

That fact can give biblical reading an edge and not congest it. Documents referencing rulers, construction projects and governmental works start to become less trite royal propaganda and more a decision-making based on environmental restraint.

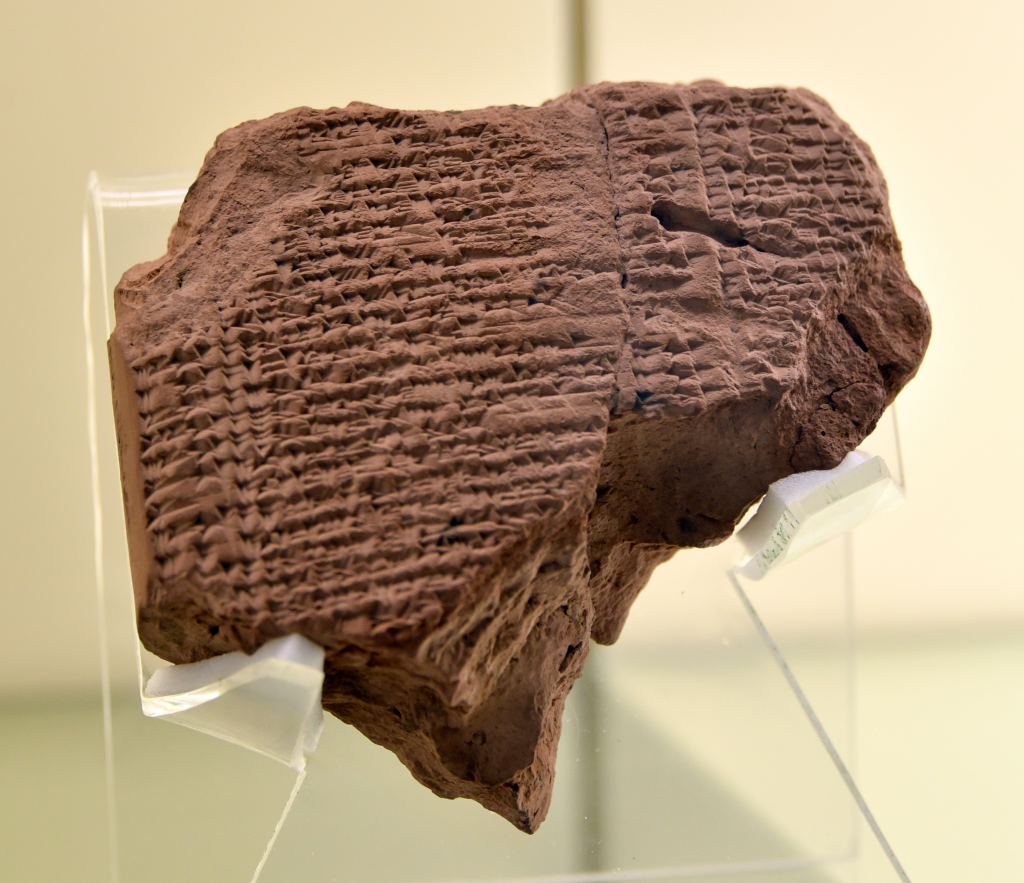

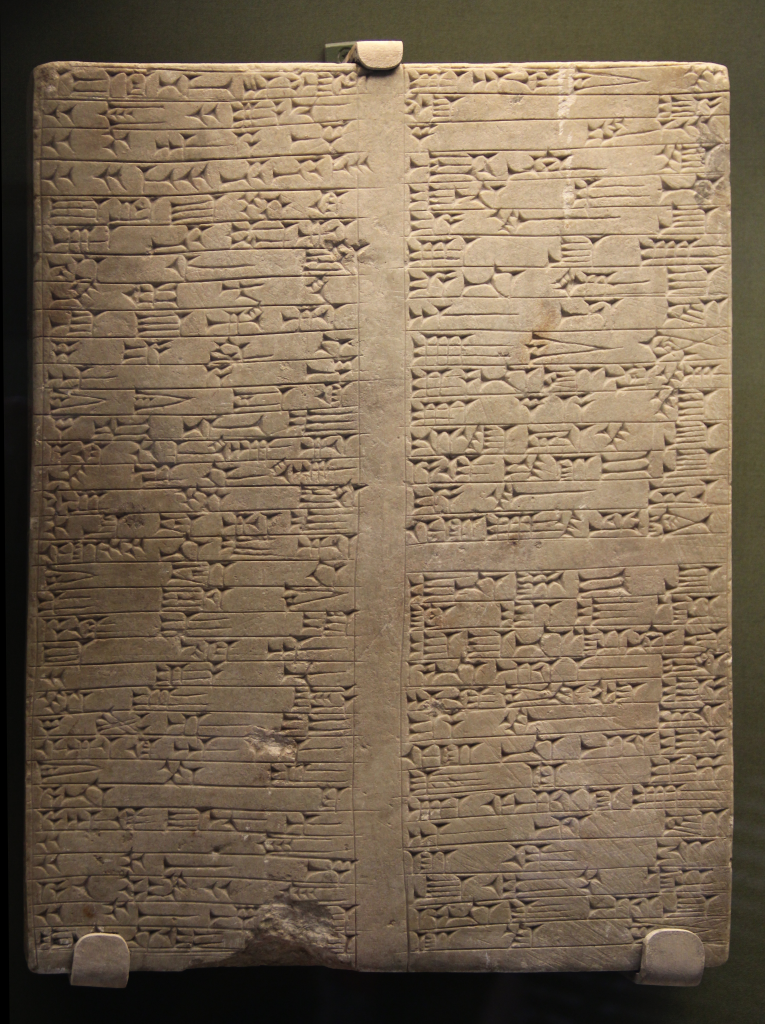

5. An Assyrian message which makes the vassal politics a reality, one inch

Biblical allusions to tribute, empire, and service to foreign kings are frequently swept through by the reader as though he were transversing the symbols of an abstract old chessboard. An example of a pottery sherd discovered in Jerusalem, approximately 1 inch (2.5 cm) in diameter and written in Akkadian cuneiform, is seen as the communication of the Assyrian court to the king of Judah with regard to late payment. It is not drama; it is visible pressure.

The lines in the Bible about rebellion, compromise, and fear, which, historically, were purely theological discussions, are no longer so against such an artifact. They are read as vocabulary of a small kingdom, which tried to breathe within the deadlines of an empire.

6. Artificial intelligence-powered dating that puts scribes into better perspective

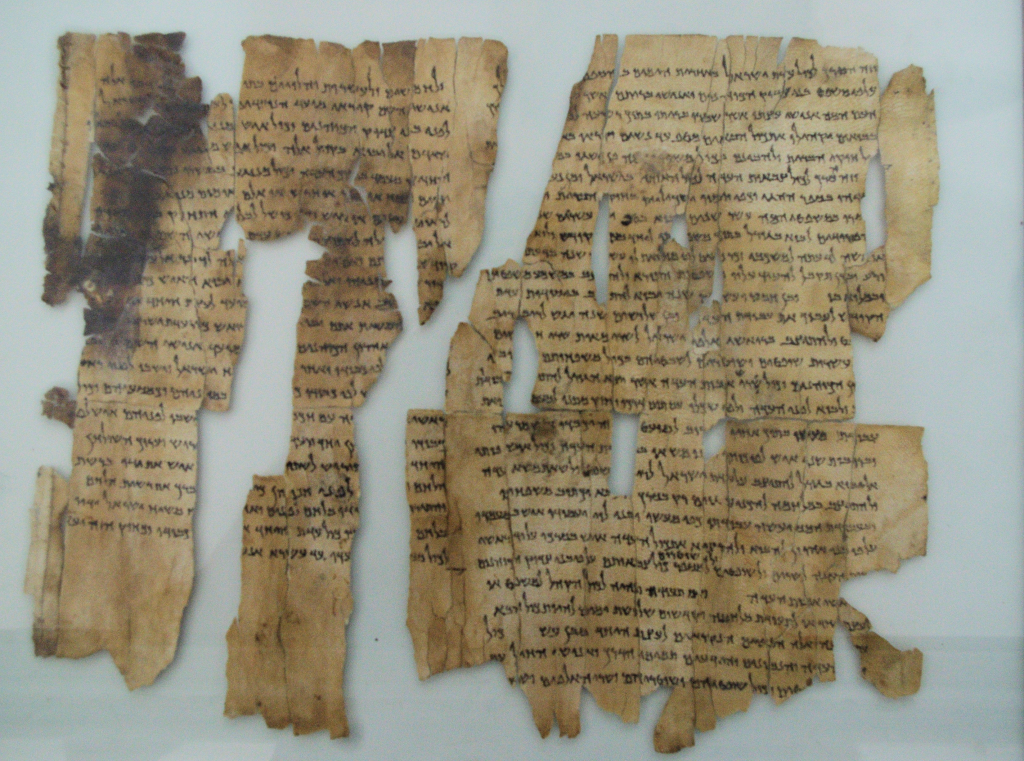

The Old Testament of the Bible is already testified to by the Dead Sea Scrolls, however, new resources have started narrowing the chronological gap. A 2025 study matched radiocarbon samples (cleaned) with AI-based handwriting analysis, a method that proposed that some manuscripts are 50-150 years older than previously calculated. Within the set that was tested, there were a few manuscripts with prior dates than the traditional paleographic dates.

The advantage to the readers is not newness. It is familiarity with procedure: Scripture as written, edited and delivered by man which pertained to specific decades, not to some general Biblical past.

What comes out throughout these instances is a discipline of attention: to place, to material boundaries, to the mundane slowness of copying and building. There are certain findings that support a name. There are those who enlighten a place. They are all asking the same mild question of the reader whether what is being dealt with is floating wisdom, or words spoken in rooms and in roads and in weather. At best archaeology never wins arguments. It puts in color, that reading may be less thin and thus more true to itself.