The Exodus occupies an awkward position: too much in the middle to be thrown away, too cumbersome to be demonstrated by a single object in a museum case. All that remains is a line of fragments of witnesses, some Egyptian writings, names of places, and cultural remnants all small unto themselves, but all the more alarming when put together.

These hints do not proceed in a straight line. Others cite remembered quarrels within Egypt; others to earlier poetry immanent in the Bible; others to what archeologists may and may not reasonably hope to discover in the Nile Delta. Combined, they indicate why the topic is still an open and serious discussion.

1. Osarseph Story of “Manetho” which resonates with the Exodus

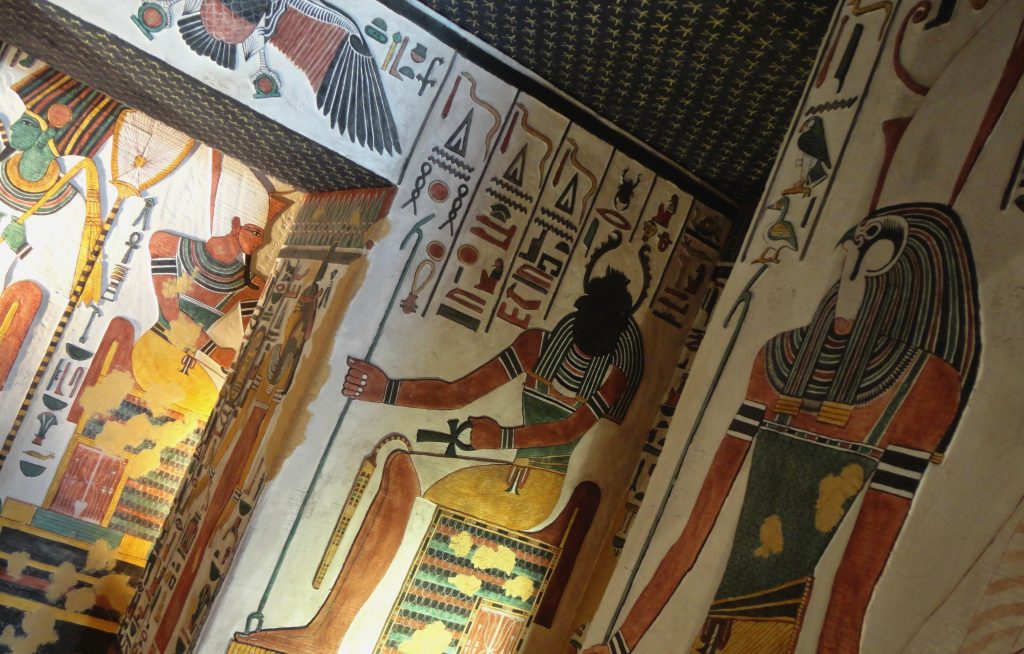

In the continuation of the Egyptian historian Manetho made by Josephus, there is a report of a fringe group of Egypt who had got together, revolted against their leader known as Osarseph and were reinforced by the north. In the story Osarseph subsequently changes his name to Moses, and the movement is depicted as being aggressive towards the Egyptian cult and temple life. The internal/external danger of the plot, an enemy of Egypt becoming one of the enemies, is rather similar to the fear of Pharaoh in the book of Exodus 1: 9-10, and this similarity is emphasized by Thomas Römer. It is not that stories are exactly the same, but rather that they shared the same narrative structure which meant that the tradition of the Exodus was spread in forms accessible to and used by ancient authors.

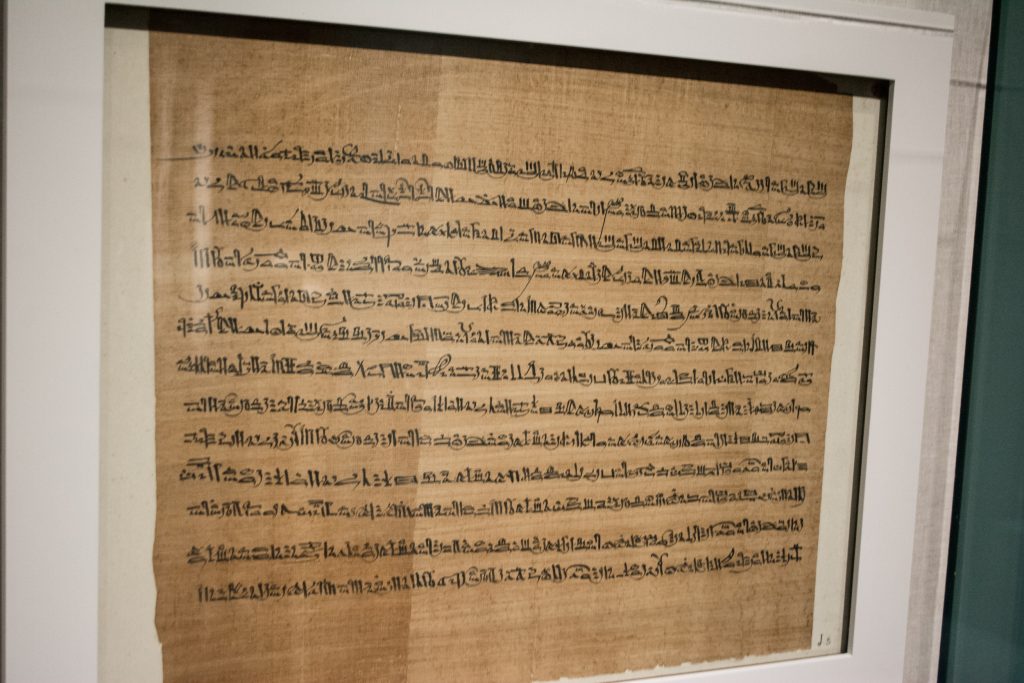

2. The Great Harris Papyrus and an Outsider of “Haru” Who Usurped the Power

The Great Harris Papyrus of Egypt was created decades later than the events it talks about, but recalls a time of anarchy after the death of Queen Tausert (late 12th century BCE). It presents a King who had made it himself, referred to with the term of irsu, as haru, that is, a genesis in Syria/Canaan/Transjordan. In the text, this figure and his followers are shown as disturbing the life of the Egyptians rituals and outlawing the offerings in the temples, as well as taxing the land. The papyrus contains a familiar structure even in the absence of a name of Israelites: foreigners in Egypt, tension of religion, and subsequent expulsion by a pharaoh who restored order.

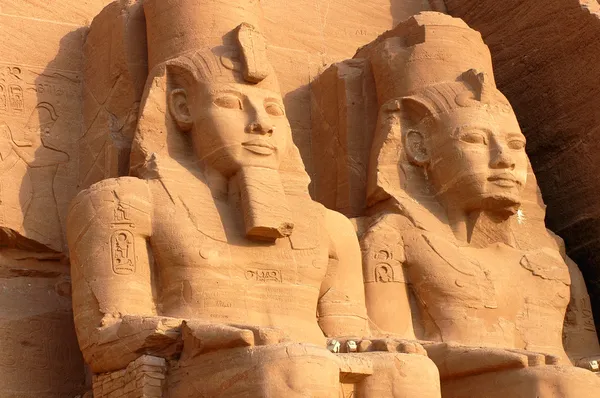

3. Swallows Flight and the Detail of Abandoned Wealth by Elephantine

One of the monuments of his second year at Elephantine has a graphic picture: and the enemies fled as the swallows fly away in front of the hawk, and the silver and gold on which they had bound their plans of foreign support, were left hanging on the way of plans that failed.

The wording is Egyptian verse, not biblical prose, but it is interesting to place it next to the books of Exodus 12:3536, where the Israelites who are just starting to leave Egypt are given silver and gold by Egyptians. The point of interest is that the convergent motifs, namely the departure under pressure, precious metals and a memory of compensation or payout, occur in sources that emerge out of dissimilar communities and agendas.

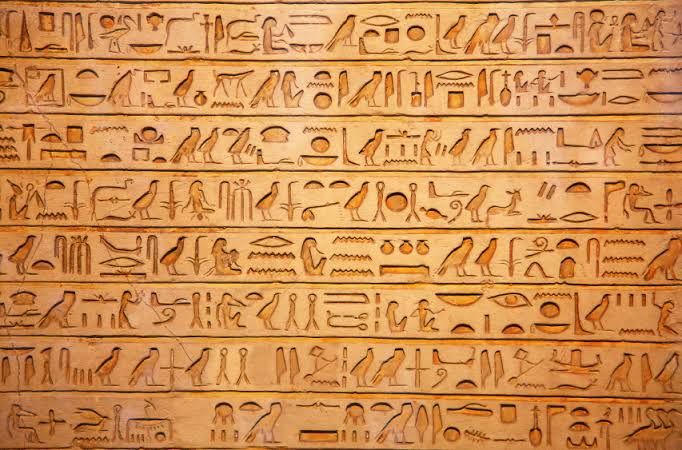

4. Ramesside Place Names That Barely Squeeze In Egyptian Usage

Onomastics: names of places, is one of the most tangible bridges between the text and the setting. The store-city Pithom and Ramses, the location of the sea crossing Yam Suph, and other Egyptian toponymes are all applied as a combination in literature of the Ramesside period.

A summary of this argument observes that Pi-Ramesse, Pi-Atum and (Pa-)Tjuf are found in the same administrative-linguistic milieu mainly around the 13th11th centuries BCE. This does not fix the date, scale or route of the Exodus, but it puts major words into an actual naming topography as opposed to an imagined, placeless, and timeless realm.

5. A Four Room House Plan in the Right Broad Period in Egypt

The excavations in western Thebes revealed one of the houses of a worker which was related to the demolition of the mortuary temple of Aya and Horemheb, which were destroyed in the 12th century BCE. The plan of the floor corresponds with the four-room house form of buildings that was generally regarded as typical of early Israeli domestic architecture in Canaan.

It is a view taken carefully by archaeologists, but the fundamental finding is the same: a house plan which would reappear in Israel later is found in Egypt at a period when Levantine people, workforce and construction teams passed through imperial structures. The clue is not of great value, but it is certainly of a particular character: it is a culturally indicative form of architecture that has already been erected on Egyptian soil, not just in subsequent strata of Israel.

6. The Levites as a Smaller Memory Group of Exodus Bearing

There is a repeated academic suggestion that the tradition of Exodus might remember a lesser group, the Levites often enough, and not a great migration of a whole people. The case is based on cultural fingerprints in clusters: Levites are named after an Egyptian style, circumcision and specific cult traditions are given prominence, and the description of tabernacle has been compared to the Egyptian military tent practice. In this framing, subsequent Israelite identity took on board an earlier migration narrative that was being held by a priestly community, which had the effect of making the tradition historically grounded and extended in terms of scope.

7. Early Biblical Poetry That Feels Older Than the Frame of Narrative

Two poems that are usually discussed in the context of being early strata of the Hebrew Bible, usually referred to as the Song of Miriam and the Song of Deborah, have been employed to experiment with how the memory of Exodus was created and circulated. The former glorifies deliverance without referring explicitly to all Israel and the latter (located in Canaan) does not have Levi in center stage. This unequal distribution leads to be one of the hints regarding the social geography: there were the groups of people who preserved Egyptian-centered memories; there were those ones which kept their own heroic cycles in Egypt. Instead of undermining the Exodus tradition, the patchwork nature of the poetry can be interpreted as that which one anticipates of old memories which circulated prior to being tied into one national story.

The debate on exodus continues due to the evidence not being a single pillar but a series of repetitive patterns that include outsiders in Egypt, disturbances with cult and labor, escaping under pressure and identity development. The most robust materials also have a weakness: they can hardly say what the contemporary readers wish them to say directly.

Nevertheless, the convergence really exists. In Egyptian literature, the concept of domestic turmoil in relation to foreigners and religion is preserved; biblical names of places appear in historical linguistics; and the earliest poetic strata of the Bible demonstrate the existence of a memory preceding the narrative in which it is framed.