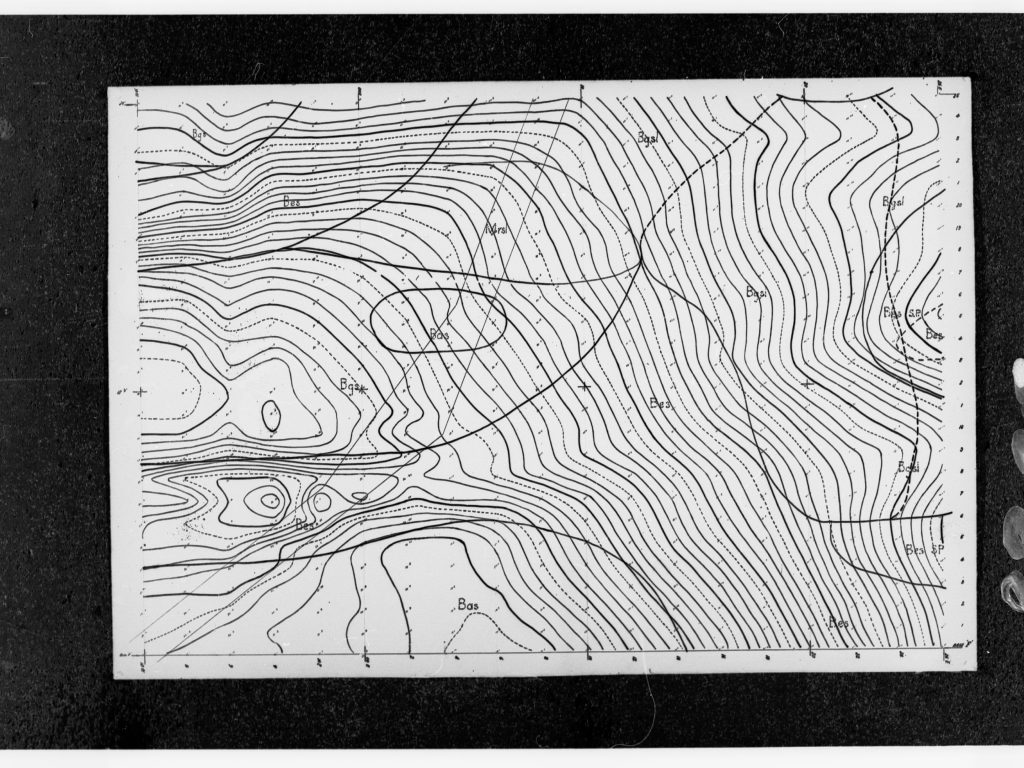

Fallout maps resemble weather forecasts but the similarity is deceptive. The lines and colors imply certainty although the calculations made behind it are based on assumptions regarding the explosion, the atmosphere, and the meaning of dose on earth.

Numerous consumer-friendly maps are constructed using models that are intended to estimate the transport and deposition of plumes, rather than telling the story of all of the complexities of the real world. It makes the outcome useful in learning, and yet easy to misunderstand and this when a map condenses days of physics into one drawing.

1. A fallout plume is not a “path” that can be treated

One of the jokes in reading is to suppose that the plume is going to be as drawn by an arrow one road, one place. Factually, the fallout dispersal is dependent on the varying altitude and time wind fields. Atmospheric dispersion work Modeling work observations that errors at a single altitude in wind direction can, at the downwind deposition, have a significant effect.

Maps usually indicate a fixed looking footprint since they cement a particular moment, meteorological record, and publishing setup. The footprint does not give a promise it is a display of the behavior of a certain collection of inputs.

2. Misunderstanding between absorbed dose and health risk (Gy vs Sv)

Fallout maps can indicate dose in grays, sieverts, or outdated units and many of its readers use them interchangeably. They are not. Units of absorbed dose is the SI unit of which is the gray, which is one joule of energy deposited in the matter per kilogram.

Health risk is normally talked of in sieverts though which has some weighting factors reflecting on the nature of radiation and a biological effect. Gy A map that is defining the amount of energy absorbed is not necessarily the likelihood of cancer or the degree of the consequences in the long-term. The absorbed dose may result in various outcomes even in the context of acute exposure depending on the exposure pattern and the tissues of the body that are exposed.

3. The legend is a threshold not a gradient to be read

Bands of colors suggest categorical thought: safe/unsafe, survivable/unsurvivable. Nevertheless, deposition and dose are tidy step continuous at a contour line; they change continuously and actual deposition is patchy.

This is particularly critical towards the border of the areas of higher doses, where a minor wind shift, change in altitude of the radioactive cloud or precipitation may shift significant dose lines. A contour would be understood to be about this level under these assumptions and not a fence.

4. The neglect of the fact that “four days” is a model, rather than a clock

The reason why many maps summarize the dose over a prescribed window is that it aids in comparing situations. The example of silo attack simulations in Scientific American talks of the dose of whole body exposure after four days, which has observed that an individual receiving four grays would have a 50 percent probability of death.

It is common belief amongst readers that the hazard ceases with the termination of the time window presented. A time window is merely an accounting frame: it may be stressing initial, sharp exposure to the exclusion of subsequent contributions, resuspension, or locations to which deposition may come after the selected cutoff.

5. Suppose that all maps are equipped with a rain system, a snow system and a “washout” system

There are simplified precipitation free models of some of the most popular fallout maps. The absence alters meaning since rain may drag particles down at a higher rate and alter concentration of deposition. It has been observed in a detailed discussion of dispersion modeling that allowing wet deposition in modeling occasionally reversed the approach to deposition prediction with a factor of three, partly due to the depletion of clouds upstream and localized rain in the future.

In a case where a map fails to model precipitation it may be used to depict the transport by wind but must not be considered as an entire representation of where radioactive material may be deposited during rainy conditions.

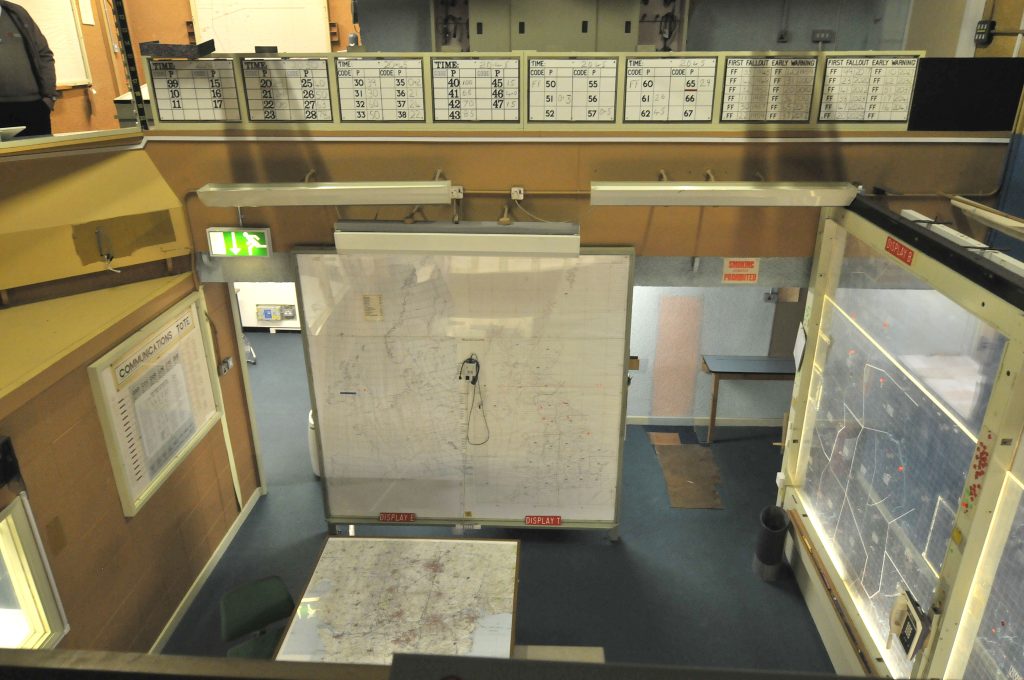

6. Assuming that “average” and “worst case” maps are describing the same event

Certain projects display an average-dose map (constructed by averaging many of the simulated days) and a worst-case map (constructed by picking the worst result at each point over many days). These are the questions of different types with similar images.

An average map will explain the average intensity of thousands of weather patterns; a worst-case map will explain how vulnerable each location will be to the worst pattern of all, although these worst results are not attained everywhere on the same day. Confusion between the two readings can either exaggerate the state of certainty either way.

7. To lose the map is an outside matter structures may vary in amount

The Fallout maps often have the dose fields of outdoor due to the inclusion of most of the models that are developed around them. Then people think of the same amount taken indoors. However, exposure can vary significantly with shelter quality, size of the building and time outdoors.

The article published in Scientific American on silo attack simulations states that individuals who are taking shelter in larger structures would get lesser dosages. The exposure of baseline may be a map, not a real prediction of people within real buildings that have walls, basements, and filtration.

Fallout maps can be considered to be organized as tools of what dose would be where under these assumptions. They can tell us why the variability of wind, the range of models, and the choice of units are far more significant than it may seem, and why the apparent sharpness of a contour line.

To read between the lines they need time and careful unit attention and time windows and what the model contains-and does not. When they are handled as the main piece of information, as opposed to details in the fine print, the map becomes an indication of uncertainty, not a sense of what is absolutely true.