There is no name in the annals of religion, perhaps, which bears so much load and controversy as Yahweh. Scholarship does not have one clean start but looks at the origins of Yahweh in pieces: inscribed and scraped-off inscriptions, pre-Hebrew poetry, and the relics of ancient religious worlds, which were later to be simplified by the authors.

What comes out is not a mere creation myth, but a complex image of how a god of specific peoples and places has come to be, over history, the only God of the Israelite and, later, Jewish tradition.

1. The first extrabiblical mention of the Yahweh is seen in an Egyptian temple list

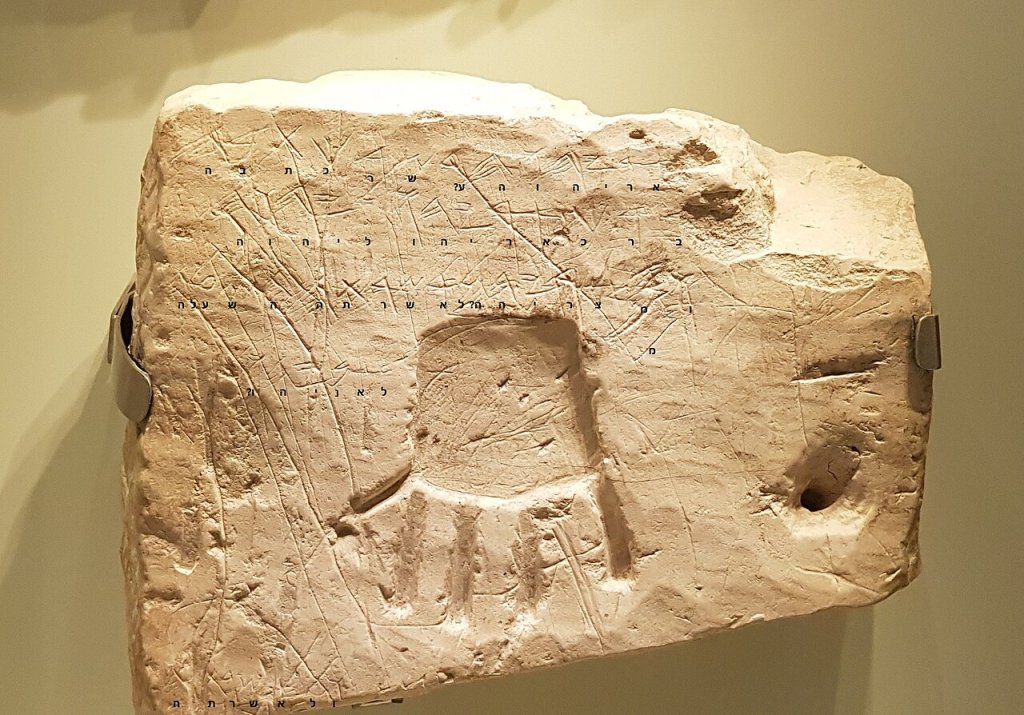

Another of the earliest extra-biblical allusions is known to be of an Egyptian scene at Soleb in Nubia, and is attributed to the reign of Amenhotep III. The phrase most commonly used in its translation is the land of shasu of Yahweh, the group termed shasu, usually, though not invariably, equated with nomadic pastoralists, is associated with the name of the God. The inscription is currently vandalized and damaged, but the significance of it is in the fact that it was first outlined in the external source rather early. Scholars quarrel over specifications of what Yahweh refers to in the word (name of a deity or name of a place), but the inscription still remains in place to debate how common the name was to other non-Israelite literature. It also focuses on the landscapes of the south, deserts, trade routes, and border zones instead of the city temples alone.

2. The first cult of Yahweh as many scholars say, was located in the southern deserts, rather than the central highlands

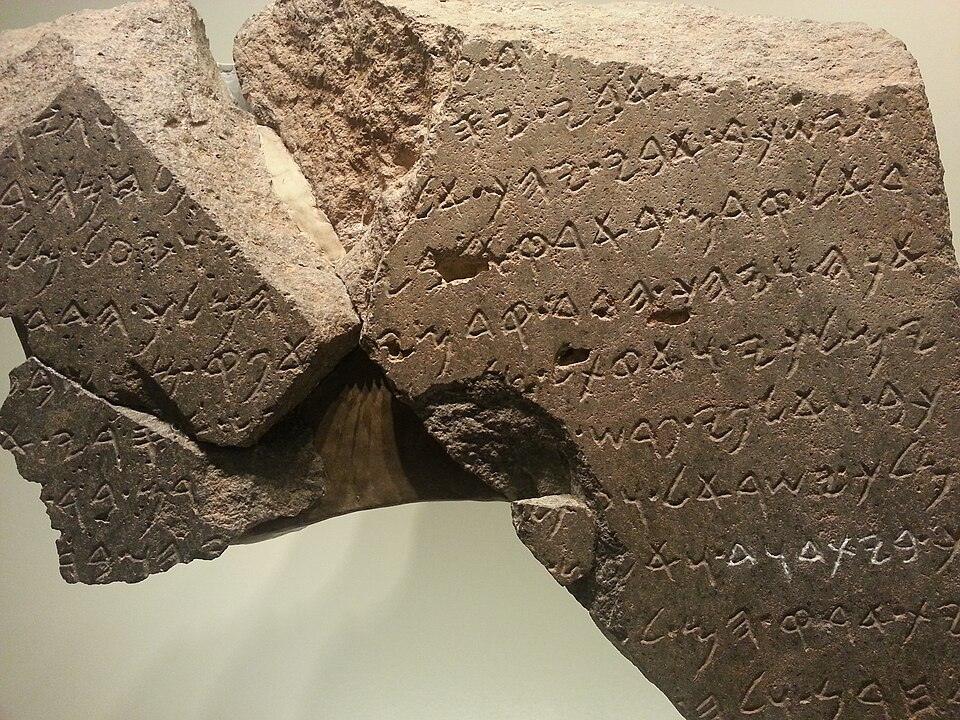

One significant scholastic trend places early Yahweh worship in the context of peoples related to the southern Levant and northwest Arabia- usually in the context of Midian, Edom or Teman. This model of southern origins is based on a mixture of an Egyptian allusion to shasu groups and biblical verses of poetry which describe Yahweh coming out of the south. In this strategy, the first profile of Yahweh is not so much a universal creator but a regional potentate whose word of mouth went with the mobile communities.

Mark S. Smith provides an overview of how contemporary studies are becoming more and more dependent upon incorporating the inscriptional, iconographic and archaeological finds as they play into reconstructing these early phases, even though the evidence is still fragmentary, hard to piece together.

3. Before monotheism, early Israelite religion is often said to have been monolatry

In general historical reconstruction, early Israelite tradition is usually defined as the cult of Yahweh without necessarily rejecting the possibility of other deities. With time, such concentration became strong denial. The brief history outlines ancient Yahwism as first monolatristic, and later as the tradition became more monotheistic other gods were subsequently denied. This historical progression is significant since it moves the question of when Yahweh came into view to when exclusive Yahweh worship ceased to be a matter of discussion.

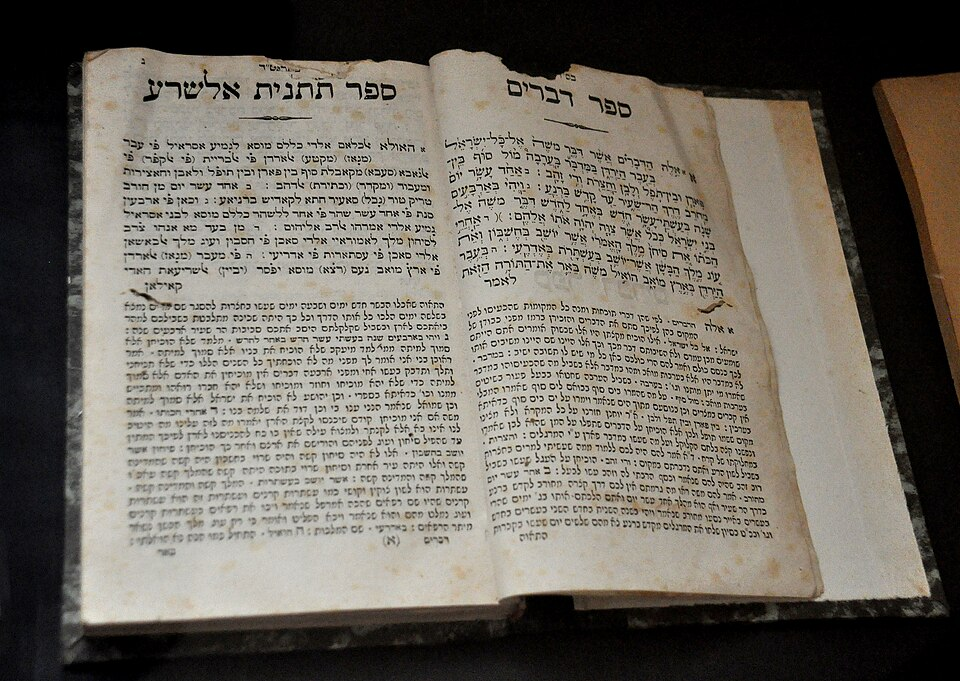

4. The ancient Hebrew poetry has some of the first Yahweh-alone language

According to some scholars, the signs of monotheism in Israel, the poetic tradition of which are quite early, seem rather unexpected. Philip D. Stern attributes rhetorical questions already in the early poetry as evidence that authors were already overstepping preference to exclusivity. In the Song of the Sea of exodus 15, the question is Who is like yourself among the gods, O YHWH? a question, Stern translates, not as an acknowledgment of competitors, but as a declaration of non-competitors.

He also points to such a poetic gesture in 2 Samuel 22: Who is a God like YHWH? Who is a Rock besides our God? and a more open one in Deuteronomy 32: There is no God besides Me. Stern does not argue that all people were monotheistic at a young age, but that a monotheistic concept-world existed in some of the earliest strata of Israelite literature (early Israelite poetry).

5. According to archaeology, worship of Yahweh was parallel to other divine beings in normal lives

Archaeological discoveries are often employed to characterize a more elaborate household religion, as well as in conjunction with the claims of the elite theology. In the academic literature (summarized by Mark S. Smith), the study of the gods in ancient Israel has been inclined toward iconography and inscriptions to chart what people seem to have done in the field, and sometimes this is in conflict with subsequent biblical ideals. Herein lies the point at which arguments about characters like Asherah take the limelight: was a goddess venerated, did a cultic icon develop, and are the earlier procedures repackaged by later writers. Smith also cautions that the reconstruction of early religion may frequently involve pulling literary remnants out of works that have been a long subject to editing, and presents the problem that historians may have sufficient resources to general patterns but rarely have sufficient resources to precision.

6. The later crisis and reforms are commonly connected with the decisive abandonment of monotheism

Scholars usually isolate the existence of an idea and its dominance even in the context of early texts that include strong exclusivist language. This is the difference that was emphasized by Stern: monotheism could be present in a poem without the norm of a community. More general historical accounts often relate the solidification of commitments to exclusive Yahweh, to the subsequent political and cultural cataclysms, such as the fall of kingdoms and the institutionalization to centralize worship. Under such a perception, monotheism has ceased to be just a dogma, it is an identity project which is perpetuated by the editing of the scribes, politics in temples, the protracted struggle of delimiting the borders of the community.

Combined, these threads form an image of the ascension of Yahweh that was too rough to be smooth, traditions running southward and traditions pointing southward, poetic assertions of unparalleled preeminence, and a gradual contraction of religious possibilities over the centuries.

The untold origins, as the term is used in the scholarship, is not so much a secret, as it is a recollection of the procedure: the narrative is based on tiny hints, which have to be read very attentively, stone fragments, marks of rituals, and the jagged edges of the old melodies.