The O.K. Corral gunfight has always existed in a narrow, cinematic form, two body lines, an opening shot, a rapid body-count, and a moral sprayed onto the dust of the streets. The record of the trial which has been preserved, the record constructed out of sworn testimonies, out of cross-examination, shows us something less neat than that, something more open and reproving.

During the longest preliminary hearing in Arizona history, 30 witnesses were called by Judge Wells Spicer. The resultant testament is of the ease with which a multifaceted dispute can be reduced to one simple story that everybody knows, and which the courtroom has maintained where popular retellings have erased.

1. The trial was a preliminary hearing and as a preliminary one it worked

The post-gunfight court proceedings did not constitute a swift procedural formality. This legal role of the hearing was to determine whether there was a sufficient cause to hold the defendants to trial, but the courtroom functioned like the verdict was in jeopardy. This fact is reinforced in the record as a civic fact that frequently fails to come up in the mythology of the West: the people of Tombstone did not merely swap tales of murder; they applied to law, witness and warring accounts, the idea of what should be understood as truth.

2. There are two cursed stories of the same minutes as enforcement or murder

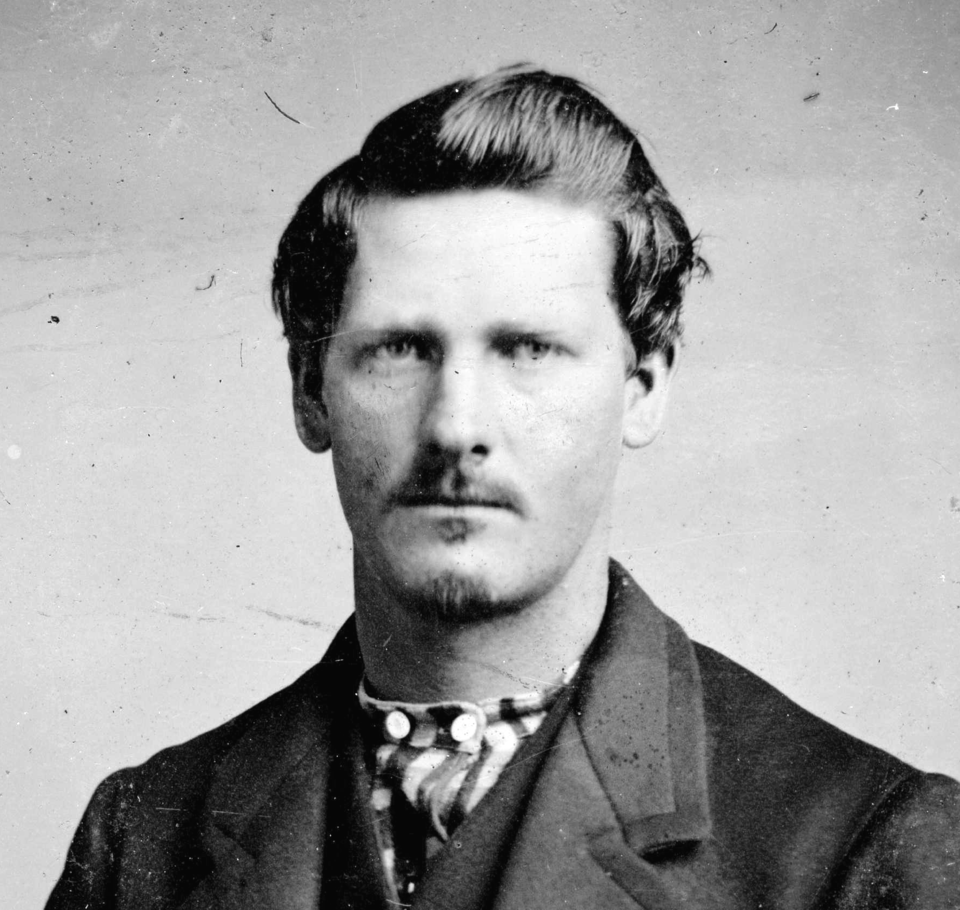

The text-based reconstruction of the dialogue reflects the framing contradiction at the very beginning. In another movie, Earps and Doc Holliday were lawmen who had no option. In the other Ike Clanton declares it murder, pure and simple, though there was no gun battle at the O.K. Corral. They were not just words, but they influenced the process of interpreting witnesses, the accusation of motives, and transforming every gesture of hands, coats, and weapons into something evident and not scene-setting.

3. The document captures an ugly antecedent of intimidation, score settlement, and career advancement

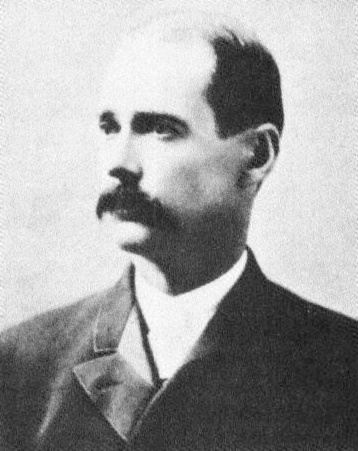

Even the statement made by Wyatt Earp under oath is less of a showdown script and rather a compilation of earlier confrontations, threats, and justifications of himself. He attributes the ultimate conflict to previous activities, supposed stealing, and political ambition, in which, he says, he had a desire to become Sheriff of this County at the approaching election, and how the taking of suspects would assist him in that object. He also tells stories of threats of death against him and his brothers and that of Holliday context that makes the spontaneous street fight a hard concept to grasp. Despite this, this testimony demonstrates as well the extent to which such a background was composed of statements, informants, and reputation knowledge as opposed to the well-documented evidence.

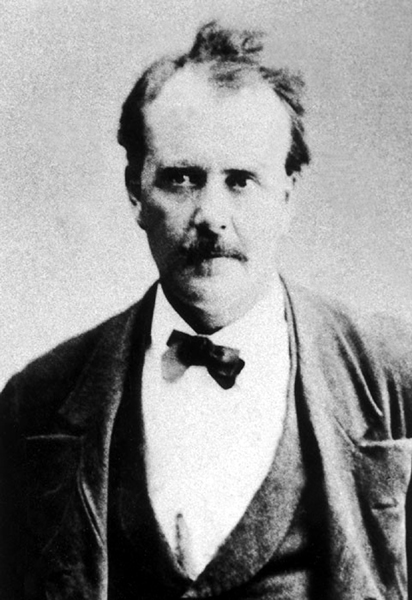

4. One warning turns out to be a hinge: I have disarmed them

Wyatt Earp wrote: Sheriff John Behan came in, and, as he approached, talked to the group, including the claim, I have disarmed them. That promise was so good a one in the telling of Wyatt, that he laid aside his pistol: I laid aside my pistol, which I had in my hand, under my coat, and put it in my overcoat pocket. The fact that Behan himself had ever disarmed anybody became no more than a side-note. It is in the middle of will and preparation, and in the book it increases the tension of what the Earps were entering into.

5. The myth of first shot is substituted by a vantage and smoke problem in the testimony at trial

Numerous re-telling approaches the initial shot as a mystery that has been resolved to either expose heroism or villainy. The initial moments in the testimony of William Allen are described using positioning: he trails the Earps and witnesses hands being raised and demands being made. He writes about the opening of an insult by the Earps and the command Virgil gives- then remembers the moment the shooting breaks out. Allen gave a testimony that it was Doc Holliday who fired first. Their backs were to me. I was behind them. The smoke came from him.” He goes ahead to say that the second shot was like a shotgun. As his description shows, the truth of things in Tombstone hinged on angle, distance, and what a man was able to see in the smoke in a small portion of the building of Fly.

6. I ain’t got no arms is featured in the record as an alleged surrender, and not as beat in the movie

In his testimony, Allen provides an element that the contemporary viewers can refer to as drama, yet the court considered it as an objective fact. He remembered Tom McLaury throwing back his coat, and saying, I haven’t a gun! and Billy Clanton telling, I do not want to fight! with hands held out. There were bullets, in an account given by Allen, as soon as those words, by the Earp party. This statement of Wyatt Earp contradicts in several key aspects, as the other side is reaching their weapons and claiming that he did not know that Tom McLaury was unarmed. The contradiction is not resolved in the transcript; it is maintained with all its rapidity, exhibiting how easily, on the part of one witness, gestures will be interpreted as surrender, and on the part of another, as a prelude to gun drawing.

7. The fact that the distance between the shoulder and the real shooting is in the record

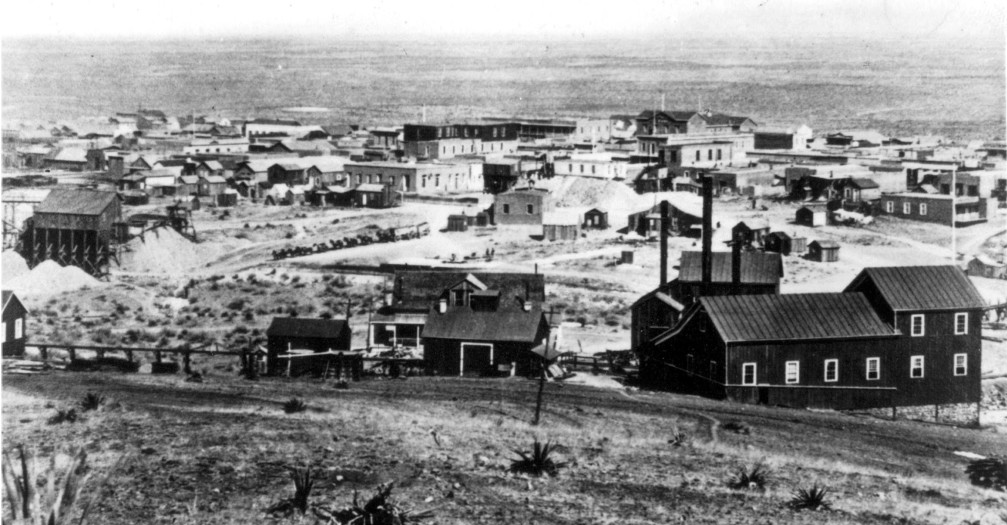

The legal case is repeatedly set in the empty lot outside the photograph gallery run by Fly and the surrounding houses as opposed to the location of the fight itself in the corral. The fact that it is a geographic particularity is important, as the common name is deceiving, promoting a simplified mental picture of one arena. Spatial information, such as corners of the street, doorways, a horse, the empty area between the gallery of photos of Fly and the building, etc. in testimony determine who saw what, how people were able to move as swiftly as they did and why people standing by, such as Allen, hurried behind buildings. Myth will be happy with a stage; the record will have it with a stampeded, roving scene.

8. The documents show Tombstone’s famous gunfight as a legal story about uncertainty

The enduring surprise in the trial material is not only disagreement, but how formally that disagreement was handled. Conflicting witness accounts, contested motives, and incompatible claims about weapons and first shots were gathered into a single institutional process, with questions, objections, and sworn statements. The result quietly rewrites the public memory: the most important “showdown” is not only in the street, but in how the town attempted to weigh credibility. Tombstone’s story, as preserved in the record, becomes less about a definitive answer and more about how communities argue their way toward one.

The trial record does not dismantle the legend by replacing it with a new certainty. It does something more historically useful: it preserves the friction. In sworn testimony, Tombstone’s most famous scene becomes a study in perspective, motivation, and the limits of eyewitness truth details that popular mythology smooths away, but the courtroom kept on the page.