The 1890s were more than just a decade of political turmoil and America’s industrial supremacy they were an era of futurism. It was all built around the World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893 in Chicago, an unprecedented exhibition of machinery, buildings, and worldwide commerce. Beside it, the World’s Parliament of Religions invited humans to explore possibilities of new religions. These celebrations did not merely signify advancement; they planted a literary explosion in utopian and science fiction literature that informed how Americans imagined cities, gender, empire, and the very fate of humankind.

1. The Utopian Boom and Its Cultural Roots

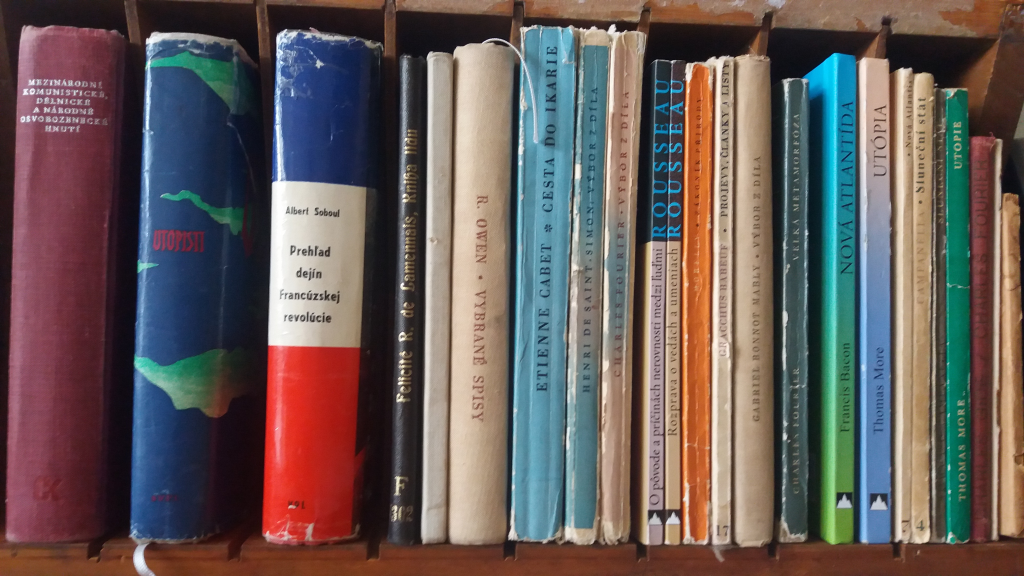

Between 1886 and 1896, over a hundred utopian novels were published in the United States, responding to the social unrest and reformist fervor of the decade. To Jean Pfaelzer, the novels were “an unparalleled literary expression of social anxiety and political hope,” deeply connected to labor movements, women’s suffrage, and urban reform movements. The popularity of the genre was because it could render political theory into tangible, comprehensible worlds visions that could stir, inspire, or alarm.

2. Bellamy’s Progressive Blueprint

Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward (1888) was the decade’s best-selling book, with only Uncle Tom’s Cabin vying for best-of-the-century ranking. Its thesis a man from 1887 waking up in 2000 and discovering that Boston is equal and harmonious provided a “definite scheme of industrial reorganization” and not a dream. Bellamy’s vision of municipal regulation of industry and planned city building directly shaped Progressive Era reforms, from city transit to urban parks. Bellamy clubs sprouted all over the country, providing an ideological umbrella for reform.

3. Dystopian Warnings: Donnelly’s Grim Vision

Whereas Boston had been a garden city in Bellamy’s imagination, Ignatius Donnelly’s Caesar’s Column (1890) was its dystopian counterpart. A populist nonconformist, Donnelly envisioned a 20th century in the grasp of an oligarchy of cold-blooded capitalists, leading to revolution and wholesale bloodshed. The “column” of bodies in Union Square was a grim allegory for what would be visited upon society if inequality were not mastered. With sales exceeding 250,000 copies, it proved dystopia could engage the public as wholeheartedly as utopia.

4. Feminist Worlds and Radical Gender Politics

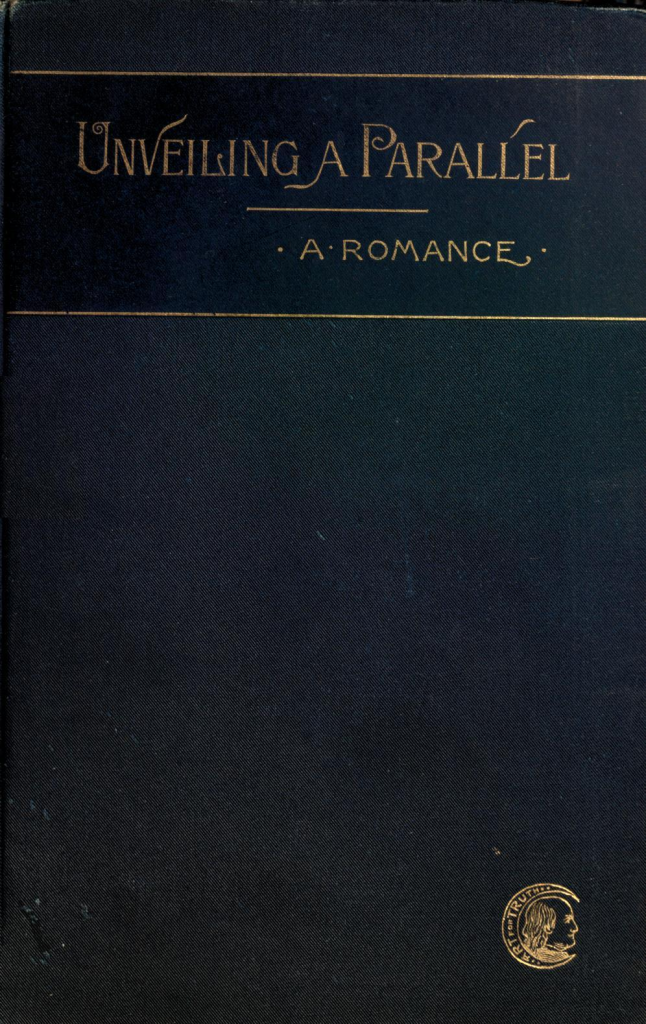

Utopian fiction was employed by women authors in order to invert gender conventions, typically representing contained feminine worlds. Mary E. Bradley Lane’s Mizora (1890) and Alice Ilgenfritz Jones and Ella Merchant’s Unveiling a Parallel (1893) set limits alternately drastically, as in the case of Unveiling‘s endingless consideration of sexual freedom. Arena Publishing, founded by Benjamin O. Flower, offered a channel for such feminist and reformist thinking, connecting it with wider currents of reformism and spiritualism. But, as later feminist theorists have pointed out, certain of these “utopias” were deformed by eugenic or racist exclusionary politics, and therefore represent as much an account of prejudice as of hope.

5. Science, Speculation, and the Martian Craze

The decade’s speculative fiction was fueled by real scientific debates. Astronomer Percival Lowell’s claims about Martian canals based on the earlier work of Giovanni Schiaparelli captivated the popular imagination. Lowell wrote of “canals” that were thousands of miles long, evidence, he believed, of a intelligent race struggling against planetary aridity. While later debunked, his vision created authors like H.G. Wells to Edgar Rice Burroughs and assisted in restoring Mars as a setting for examining human desires and terrors regarding technology, survival, and encounter with the Other.

6. Time Travel and Alternative Histories

American writers were not slow to test the possibilities of temporal jumps. Edward Everett Hale’s “Hands Off” (1881) prefigured the “butterfly effect” by demonstrating the consequences of rescuing one life in the past to doom the future to ruin. Mark Twain’s A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court (1889) employed time travel to satirize imperialism, telling the disastrous collision of high technology and medieval culture. Castello Holford’s Aristopia (1895) explored alternative history, projecting a socialist utopia out of a different colonial past.

7. Technology as Utopian Engine

Most utopias of the 1890s embraced technological transformation as the path to social reform. Byron Alden Brooks’s Earth Revisited (1893) included terraforming the Sahara and communicating with Martians. John Jacob Astor IV’s A Journey in Other Worlds (1894) envisioned an American empire extending into the solar system. They were a Baconian faith in mastery over nature, but also posed the question still asked today who is in charge of technology and for what ends.

8. Spirituality, Evolution, and the Future of Humankind

Futurism at the time was infused with evolutionary theory, Darwinian or distorted into eugenics. Most people assumed that humans might evolve into a better animal or founder catastrophically. Evolutionary thinking found its way into political and metropolitan ideals, religion, and such movements as New Thought, equating spiritual and physical health with human progress.

1890s’ utopian and dystopian fiction was not escapist fantasy. It was its time’s projection industrial discontent, imperialist yearning, feminist indignation, scientific awe applied to futures imagined. Reading them today, one finds both the high hopes and the profound fears of an age on the eve of the modern world.