What if some of the greatest villains in history weren’t the black-and-white characters we’ve learned to hate? For centuries, best-selling stories that have been fueled by propaganda, politics, and even Shakespearean theatre have made some individuals irredeemable. But when you read the record, the reality is often considerably more complicated, and occasionally, appalling to sympathize with.

Revisionist historians, newly available documents, and new cultural insights are uncovering that some of these supposed traitors, tyrants, and plotters were actually motivated by loyalty, principle, or necessity. And although what they did was questionable (and in some instances, brutal), the reasons for it are more nuanced than is provided by the one-dimensional “villain” label.

These are nine figures whose reputations are in need of a revision because the difference between hero and villain is thinner than we imagine.

1. Judas Iscariot: The Faithful Betrayer?

Judas Iscariot’s name has become synonymous with betrayal, but the revelation of the Gospel of Judas in the 1970s made things more complicated. According to this ancient text, Judas was acting on a request from Jesus himself, triggering the chain of events that resulted in the crucifixion and resurrection. Without his so-called betrayal, perhaps Christian theology as we understand it would not have existed.

Some Christian sects in early times even glorified Judas for completing prophecy, and historians note that the decades-posterior gospels contain conflicting stories. As PEOPLE reminds us, his posthumous reputation as the ultimate turncoat perhaps owes more to subsequent scapegoating than to the actuality of his actions.

2. Brutus: Defender of the Roman Republic

Marcus Junius Brutus is forever remembered as the fellow who stabbed Julius Caesar, but in his own mind, he was rescuing Rome from dictatorship. Caesar’s concentration of power in his own hands looked terminally like an end to the Republic, and republican-minded Brutus joined the plot to prevent it.

Although the assassination failed, triggering civil war and opening the doors to imperialism, Brutus was motivated by a desire to protect democracy. According to historical reports, he acted out of a sense of responsibility, not self-interest.

3. Captain William Bligh: Misjudged as a Tyrant

Due to Mutiny on the Bounty, Captain William Bligh is generally depicted as a sadistic commander. Actually, history indicates that his strictness was typical for the period, and the mutiny was largely a result of his crew’s resistance to leaving the enjoyment of Tahiti behind rather than his command.

After being put adrift, Bligh sailed more than 3,600 miles to safety a feat of seamanship attesting to his skill and determination. The image of the tyrant comes mainly from the mutineers’ requirement to explain their uprising.

4. Richard III: Victim of Tudor Propaganda

Shakespeare’s hunchbacked bad guy was possibly more legend than reality. Although Richard III has been accused for centuries of killing his nephews the Princes in the Tower there is no concrete evidence. Some claim that Henry VII had as much motive.

In the course of his brief reign, Richard enacted reforms to advance justice and shield commoners. The Tudor dynasty, keen to legitimize its grip on power, had every motive to vilify him. The 2012 find of his skeleton even dispelled myths over his deformity, proposing his “evil” reputation was a masterclass in political mudslinging.

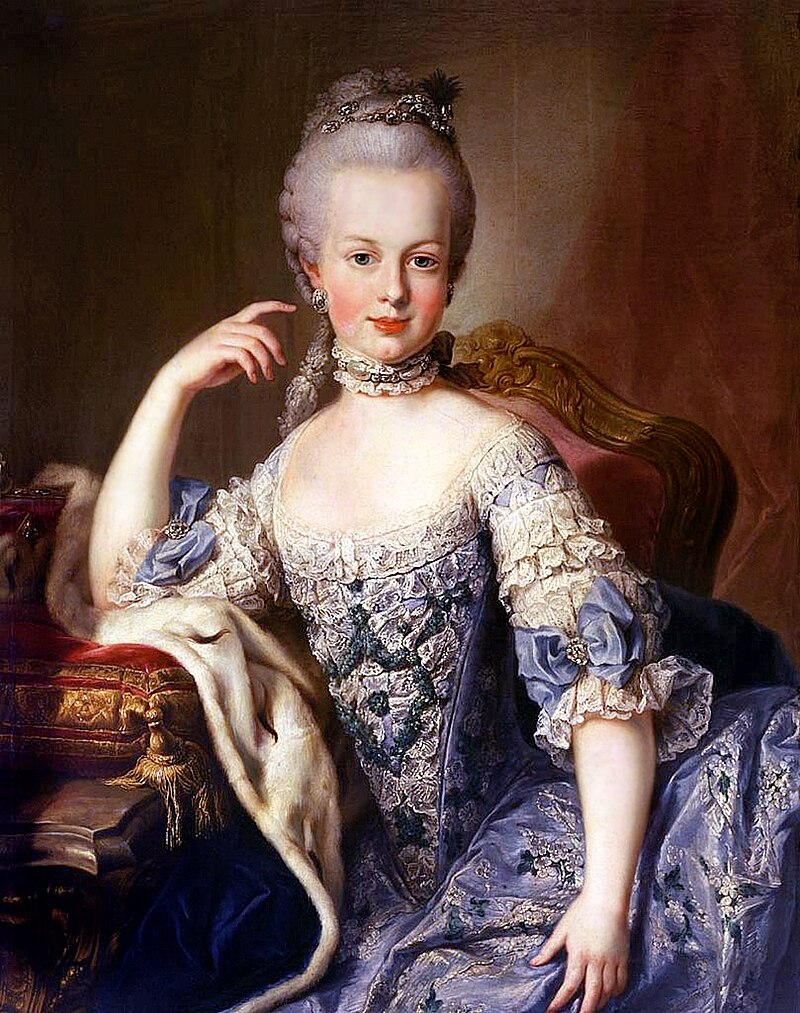

5. Marie Antoinette: The Misquoted Queen

“Let them eat cake” has become shorthand for royal callousness, but Marie Antoinette never said those words. The phrase is older than she is and was probably assigned to her as revolutionary propaganda.

She did live extravagantly, but she also donated to charitable causes and advocated reforms that would assist the poor. Her Austrian birth and symbolic position as queen made her a convenient target for France’s profound economic troubles.

6. Benedict Arnold: Patriot Turned Outcast

Prior to his surname becoming synonymous with treachery, Benedict Arnold was among the most accomplished generals of the American Revolution, contributing significantly to successes such as Saratoga. However, recurring slights at the hands of Congress, financial struggles, and feelings of betrayal compelled him toward the British.

His betrayal was reprehensible, but learning about the personal and political grievances which took him there makes his tale less one of simple evil and more a tale of disillusionment.

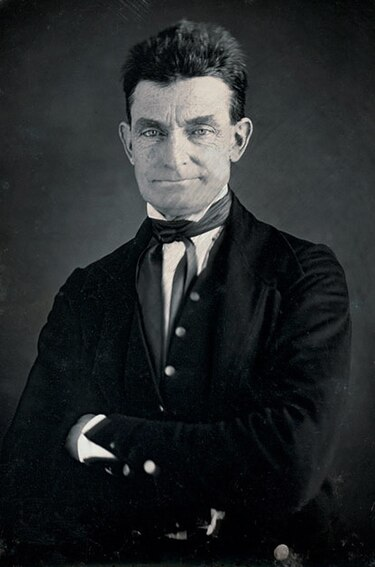

7. John Brown: The Fanatic Who Saw Clearly

During his lifetime, abolitionist John Brown was dismissed even by some of his own allies as an extremist. His 1859 Harpers Ferry raid was a failure, and he was hanged for treason. But ultimately, history has vindicated largely his conviction that slavery would only cease through violence.

As Frederick Douglass later mused, Brown’s actions were the match that lit the Civil War. His moral courage, however coupled with violent means, put him decidedly on the side of right in history.

8. Emperor Nero: More Builder Than Burner

The picture of Nero “fiddling while Rome burned” is all myth he wasn’t even in the city when the Great Fire began. Accounts of the time indicate that he organized relief and rebuilt the city with better infrastructure.

Whereas hostile ancient historians overstated his brutality, Nero was also an arts patron, lowered taxes, and spoke for oppressed groups such as slaves. His actual sin could have been alienating the Senate, which influenced his lasting reputation.

9. Mata Hari: The Convenient Scapegoat

Shooting by firing squad in 1917 for espionage, Mata Hari is still one of history’s best-known “femme fatales.” However, the case against her was weak, and scholars now think that she was a symbolic rather than a threat-environmental spy target.

As a foreign-born woman with a tawdry reputation, she was an obvious fall person for France’s war failures. Her trial was more spectacle than justice, and so her tale is one of warning about fear and politics trumping truth.

History adores its villains, but as these tales illustrate, the truth is far less black and white. Through a re-examination of the evidence and challenging the stories we’ve been told, we discover a more complex, human history one in which even the so-called worst among us might have been doing the best they could from conviction, compulsion, or circumstance. Ultimately, re-examining these individuals does not justify their actions, but it does serve as a reminder that history is recorded not only by the conquerors, but by the chroniclers.