The announced shutdown of a Tyson Foods beef processing plant in Lexington, Nebraska, and scaling back operations in Amarillo, Texas sent shockwaves across cattle country. The reported job losses, as many as 3,200 jobs in Nebraska and 1,700 in Texas, underlined a worsening supply crisis that has been several years in the making. The U.S. cattle herd is at its lowest in nearly 75 years, a contraction driven by drought, inflation, and rising operational costs.

1. Historic Low in Cattle Supply

The Department of Agriculture predicts another 2 percent drop for 2026, further deepening a slide that began with years of punishing drought. “‘The biggest thing has been drought,”‘ said Eric Belasco with Montana State University, which stripped grasslands across the West and Plains and left ranchers without adequate feed or water. This scarcity has forced ranchers to sell breeding cows early, slowing rebuilding herds to a crawl.

2. Financial Losses Forcing Corporate Retrenchment

The company’s beef business lost $426 million in the 12 months through September 27, 2025, and could lose as much as $600 million in fiscal 2026. The Amarillo plant, which can take on roughly 6,000 head of cattle a day, will move to a single shift. The Lexington facility will be closed outright by January 2026. While the company said it would ramp up production at other plants to meet demand, the move underlines a wider industry reality: tight supplies and high input costs are gutting profitability.

3. Economic Ripple Effects in Rural Areas

The city of Lexington, Nebraska, with an estimated 11,500 residents, now faces the loss of its largest employer. Nebraska Senator Pete Ricketts said the closure was “especially heartbreaking around the holidays.” The senator also added: “A devastating impact on a truly wonderful community.” The layoffs put at risk one of the major industrial employers in Amarillo, adding to economic pressure in the state where farming generates more than $13 billion annually.

4. Inflation and Consumer Price Pressures:

Retail beef prices have surged from $8.51-the average per pound in August 2024-to $9.85 a year later. On restaurant menus, those prices are not that far behind. Skeeter Miller operates County Line barbecue restaurants. He says he now pays nearly double what he paid for hamburger meat just a few months ago. That forces tough decisions about portion sizes and what goes on the menu.

5. Supply Chain Disruptions and Policy Responses:

The USDA’s Grazing Action Plan includes opening up more federally managed land to grazing, easing permitting, and expanding disaster relief programs. Still, since 93% of Texas land is privately owned, ranchers like Bryan Luensmann remain skeptical as to how that plan would work within state borders. A recent Trump proposal to import more beef from Argentina has also met skepticism from Texas ranchers who say that will make only an extremely limited impact on prime cuts and might also further unsettle markets.

6. Long-Term Herd Rebuilding Challenges:

“There’s really nothing anybody can do to change this very quickly,” Derrell Peel of Oklahoma State University said. It takes roughly two years to bring cattle to market and several to rebuild herds, so high market prices for young females typically create an incentive to sell them for meat rather than retaining them for breeding-slowing recoveries further.

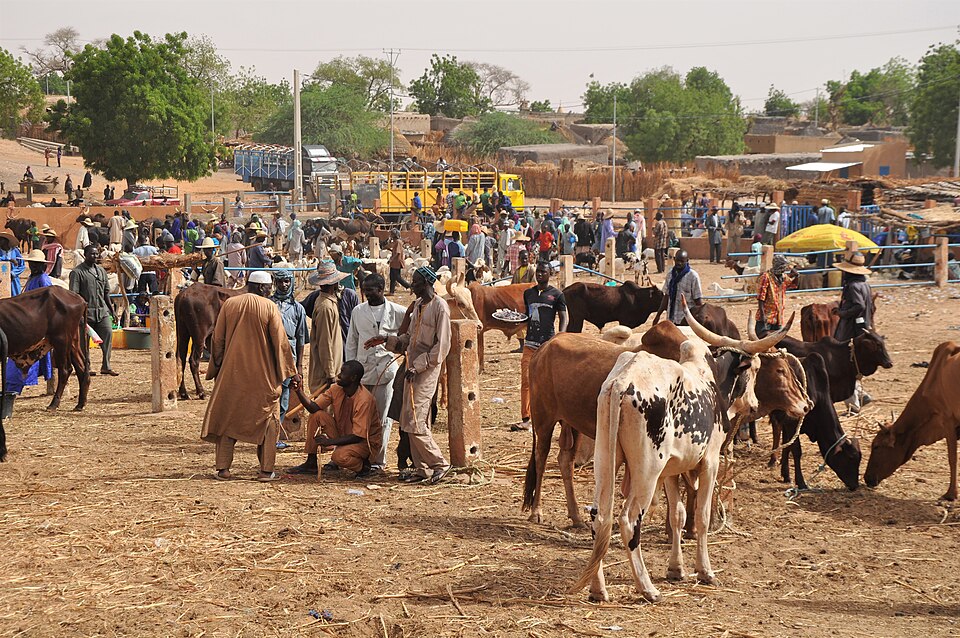

7. Community Adaptation and Resilience:

Ranchers in Raywood, Texas, still gather weekly at the local livestock market-even when the prospects for their industry were at their direst. Owner Kory Brett has organized special replacement sales to help ranchers rebuild herds after drought-forced sell-offs. “They need, you know, 40, 50, 60, maybe 100 [cattle] because of the drought,” Brett said, underscoring efforts such as his to keep rural economies afloat.

8. Coping with Economic Stress through Layoffs:

Experts say the best way to push through uncertainty is to focus on what one can do. In the case of workers, knowing relocation benefits and job openings at other Tyson plants lends some stability. There are state and federal programs to help these communities cushion the blows from lost jobs and to diversify their economies. Social connections-like the fact that Raywood Livestock Market meets for coffee and breakfast nearly every morning-sustain morale.

All of these factors come together-the tightening cattle supply, corporate restructuring, and rising consumer prices-in one overarching long-term problem now facing America’s beef industry. Recovery will take some time, will be assisted by initiatives at the federal level, and by resilience efforts coming from the localities themselves. Strategic investment and sustained community support are needed.