It was rain to start, of a kind that local people had experienced countless times before. Within hours, familiar monsoon showers turned into torrents of water so powerful that one survivor in Aceh, Indonesia, said the current “could kill an elephant.” In Indonesia, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Malaysia, and Vietnam combined, over 1,300 lives have been lost in one of the most destructive flooding events in recent history. The stories now emerging from these submerged communities reveal not only the scale of the destruction but also the resilience and solidarity that will shape recovery.

1. The Night the Waters Rose

In Pidie Jaya district, Aminah Ali woke to a roar unlike anything she had ever heard. By first light, she was on her roof, surrounded by three metres of floodwater stretching to the horizon. “I saw many houses being swept away,” she recalled, her belongings reduced to a single shirt. Busra Ishak from Aceh clung to a coconut tree for 12 hours after his home disappeared in the surge. His sister was among the dead. In Hat Yai, southern Thailand, Natchanun Insuwano and his parents survived waist-deep waters with only one bottle of water over three days, awaiting help that came too late.

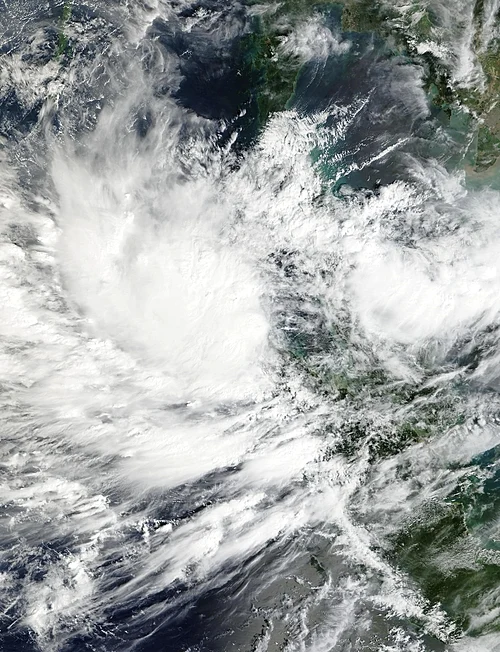

2. A Disaster Beyond Seasonal Flooding

They attribute the factors that triggered this calamity to the formation of Cyclone Senyar over the Malacca Strait and Cyclone Ditwah in Sri Lanka; these are meteorological formations seen very rarely. In Hat Yai, alone, 335 mm of rain fell in one day-the highest in 300 years-and overwhelmed the drainage systems, flooding the urban plains. Flooding has surpassed even the breadth of the impact caused by the 2004 tsunami, according to President Anura Kumara Dissanayake of Sri Lanka, who termed it “the most challenging natural disaster in our history.”

3. Failures in Warning and Preparedness

The Thai government’s failures in disaster warnings have been strongly condemned. People in Hat Yai were warned about water being up to their waist, and just a few hours later, it reached their chest level. Investigations found an antiquated early warning system linked with unreliable weather monitoring, coupled with coordination among the different 48 agencies that are involved. Flood forecasts were only 33% accurate a day in advance, while communications equipment often failed, leaving communities vulnerable.

4. Humanitarian Needs on an Immense Scale

Across Sumatra, 11 bridges and stretches of the national highway have been cut. In Aceh, survivors queue for hours at petrol stations as the prices of basics have shot up – chillies are now 300,000 rupiah per kilo. Aid groups are warning food shortages could become acute in days if supply routes are not restored. The Indonesian government has sent 34,000 tons of rice and 6.8 million liters of cooking oil, while charities such as Islamic Relief race to get tonnes of food delivered by navy vessel.

5. Trauma and Psychological Recovery

Danger did not pass with the waters for many. In Hat Yai, Chutikan Panpit was out inspecting flood levels when she was bitten by a Malayan pit viper and had to wait 32 hours for treatment. Survivors speak of panic triggered by the sound of rain, a common post-disaster symptom.

Psychologists underscore that safe spaces, routine restoration, and community support are required in countering trauma-especially among children who lost homes or family members.

6. Community-Based Resilience

Grassroots initiatives take root in the devastation. Volunteers prepare rice parcels for displaced families at the Dalugala Thakiya Mosque in Colombo, Sri Lanka. In Aceh, people share scavenged food and clean water among neighbors. The IFRC went on to cite nature-based solutions like the planting of mangroves and trees as reducing flood risks over the longer term, plus better social protection systems which would instantly offer cash, food, and medicine immediately after disasters.

7. Political and Policy Implications

The flood crisis has turned into a leadership test. In Thailand, Prime Minister Anutin Charnvirakul is under increasing criticism only some months into the job. Hat Yai’s district and police chiefs have been sacked, and the mayor has apologised for underestimating the danger. According to policy analysts, decentralization of disaster management, a more empowered governor, and land use regulations in areas prone to flooding are ways repeats of such failures can be avoided.

8. The Road to Rebuilding

Recovery will be slow. Across Southeast Asia, more than 4 million people were affected and over 1.2 million displaced. In Indonesia’s Palembayan, residents wade through mud and wreckage, salvaging motorcycles and documents. In Malaysia’s Perlis state, families shelter in tents, waiting for water and electricity to return.

At the same time, aid agencies warn that unless there is sustained international support, communities will face long struggles to rebuild livelihoods, restore infrastructure, and heal from the psychological wounds left by Asia’s deadliest floods in decades.