Life on the Roman frontier was not as clean and orderly as people generally thought. A microscopic record of struggle has just been discovered by the recent archaeological investigation at Vindolanda, a fort located just south of Hadrian’s Wall, in the eggs of roundworm, whipworm, and in traces of Giardia duodenalis deposited in the sediment of ancient latrine drains. Besides being the first record of Giardia in Roman Britain, the finding reported in Parasitology, illuminates the continuous health problems of the soldiers and families living in the empire’s remote areas.

1. A Fort on the Edge of Empire

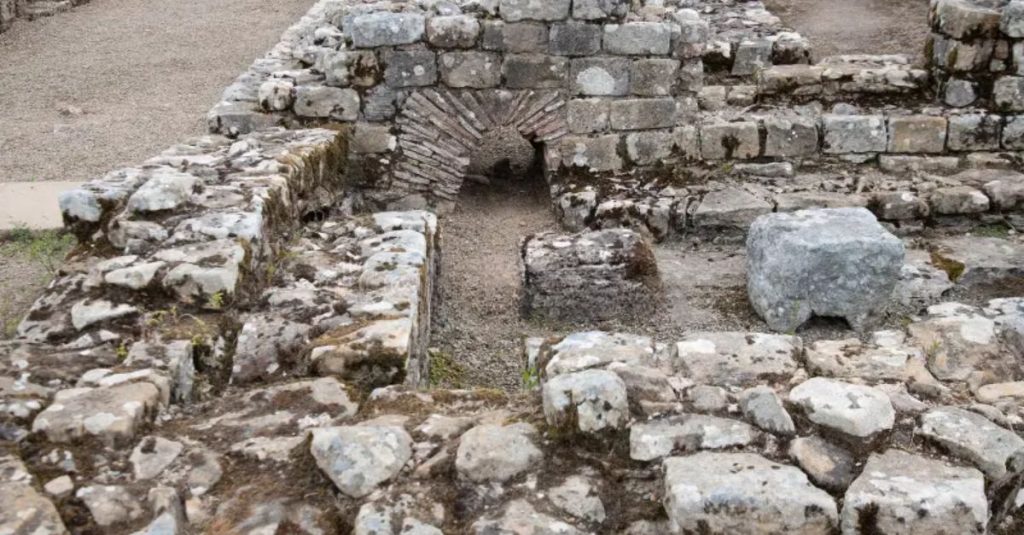

Vindolanda, a site of Roman occupation from the 1st to the 4th century CE, served as a vital line of defense against tribal invasions of the north in Britannia. The fort, which suffered no damage through time due to its preservation in anaerobic mud layers, has provided thousands of the ancient world’s remains – from ink-written wooden tablets to leather shoes and now biological traces of diseases. Being near Hadrian’s Wall, which was built in 122 CE, Vindolanda was the place where infantry, cavalry, and archers from different parts of the empire lived together forming a diverse but closely-knit community.

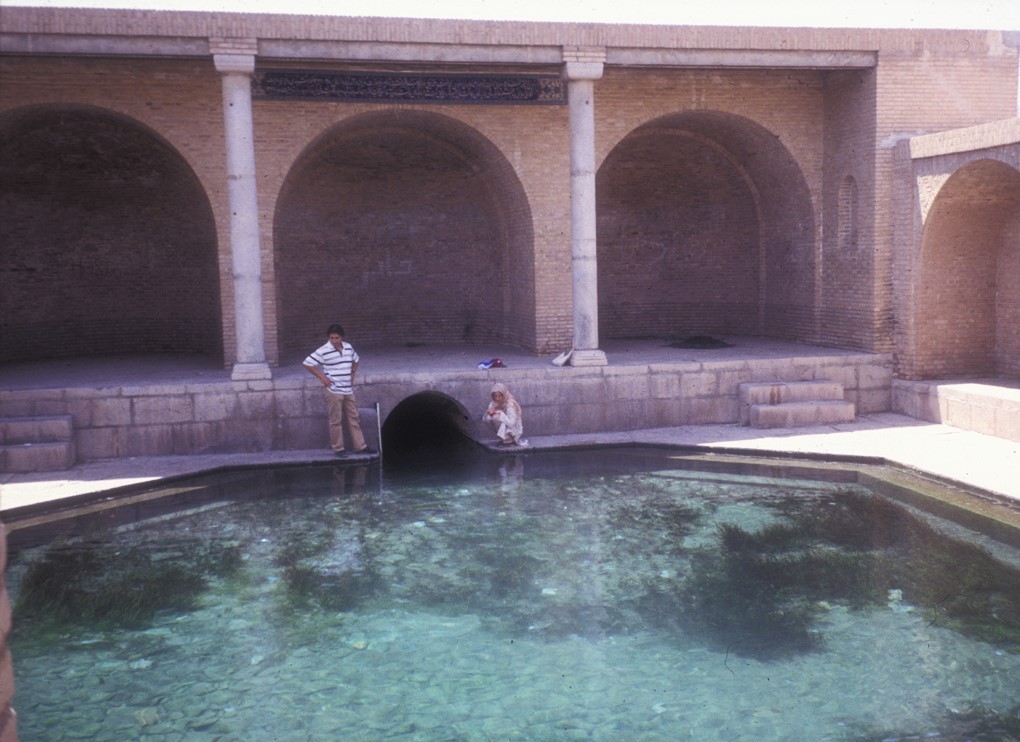

2. The Latrine Drain as a Time Capsule

The London and Oxford researchers took 58 sediment samples from a nine-meter sewer drain that was connected to a communal latrine in the fort’s bath complex. Besides soil, several objects like Roman beads, pottery, and animal bones were also found. On the microscopic level, roundworm eggs of up to 30 cm in length and whipworm eggs of about 5 cm in length were found. Both worms are spread through fecal contamination of food, water, or hands. In a sample where both types of worms were found, further testing by ELISA resulted in the identification of Giardia duodenalis a microscopic protozoan parasite that causes giardiasis.

3. First Evidence of Giardia in Roman Britain

Whipworm and roundworm have been detected at some Roman archaeological sites in Britain, while the presence of Giardia is new here. The senior author Dr. Piers Mitchell stated, “It is not clear whether this parasite was in the U.K. before the Roman period.” In the case of Giardia, the symptoms may include acute diarrhea and dehydration. Still, if chronic, the patient may suffer from irritable bowel, arthritis, allergies, and muscle pain. Besides, the prolonged infection can slow down children’s growth and reduce the cognitive development.

4. Health Risks for Soldiers and Families

Despite the official prohibition of marriage among Roman soldiers, the presence of preserved children’s shoes as one of the evidences has led to the assumption that families lived inside the fort. Dr. Mitchell urged, “Diarrhea can cause dehydration in all age groups, but it is children who are most likely to die from it.” Chronic parasitic infections may result in the weakening of soldiers making them less fit for the army and at the same time, the health of their dependents may be compromised. Dr. Marissa Ledger explained that “their doctors could hardly do anything to get rid of these parasites, so the symptoms often continued.”

5. Sanitation Systems and Their Limits

There were communal latrines at Vindolanda where stone seats, wooden toilet fixtures, and a water trough for handwashing were available, and the waste was flushed into a sewer system. However, as Dr. Patrik Flammer pointed out, “this still did not ensure complete safety for the soldiers as they could still infect each other.” Advanced sanitation facilities like aqueducts, public baths, and sewer networks, which existed throughout the Roman Empire, made life cleaner and less smelly but did not lower the number of parasitic infections. The most probable reasons for the continuation of the parasites might be warm communal bath waters that were changed infrequently, and the use of human feces as crop fertilizer.

6. Comparative Parasitology in Ancient Civilizations

The parasitic profile unveiled at Vindolanda resembles that of the Roman legionary camp sites of Carnuntum in Austria, Valkenburg in the Netherlands, and Bearsden in Scotland. The urban centers of London and York had a wider variety that included fish and meat tapeworms. The pre-Roman Bronze and Iron Age Europe had already been contaminated with whipworm and roundworm, nevertheless, Giardia had only been reported in places like Turkey and Italy. The process of spreading parasites was dependent on trade, troop movements, and the use of common infrastructure.

7. Broader Public Health Lessons from Rome

Among public health measures of Ancient Rome were constructions such as aqueducts and laws enacted to safeguard water sources which clearly demonstrated that the Romans understood that hygiene was of social importance. However, since they had no knowledge of microorganisms, these measures could not interrupt the transmission cycles of fecal-oral parasites. One such practice was fertilizing crops with unprocessed human waste, which, therefore, allowed the infection to be reintroduced. The fact that the parasites were able to survive even after sanitation measures were put in place is a warning for today’s public health that the provision of infrastructures without microbial awareness and preventive measures will still be insufficient.

8. Archaeology as a Window into Daily Life

The very small remains found in the drains at Vindolanda go well with the fort’s rich record of artifacts, thus they help to draw a more vivid picture of life on a frontier. They point out that apart from the troops’ military duties and the families’ normal routines, the inhabitants were faced with chronic diseases. Dr. Andrew Birley of the Vindolanda Charitable Trust, said, “the ongoing work on the site keeps unearthing evidence that is helping us to understand the terrible difficulties of those who were sent to this northwestern frontier of the Roman Empire nearly 2,000 years ago.”

From the grandness of Roman engineering to the smallest traces of disease, the latrine sediments of Vindolanda tell us that history is not only written in the form of stone walls and inscriptions but also in the unseen struggles that are preserved under our feet.