“History matters,” Richard Elliott Friedman asserted in an introduction that struck right at the heart of a long-standing controversy in the realm of religion. Did the Exodus even occur? For thousands of years, the legend of a deliverance from Egypt has been told not simply as history, but as religious history but not everyone has been convinced that if it didn’t leave bodies, it shouldn’t be considered more than a legend. Lately, though, in a way that, through the mosaic of archaeology, and scripture, and cultural imprints, the conversation is beginning to turn.

Now, the record, of course, is complicated, layered, and involves everything from the Egyptian texts of foreign-led revolts to the oldest songs of the Bible, which speak of a smaller migrant group. Instead, a simplistic verification or refutation is replaced by a more complete understanding of those circumstances which may have influenced Israelite identity and the development of monotheism. Below are ten of the most intriguing evidence.

1. The Story of Osarseph and Its Relationship to Moses’ Exodus

“And thus says an ancient historian named Manetho that an uprising did take place under Pharaoh Amenophis, led by the priest with the leprosy, Osarseph. He joined forces with the Hyksos of Canaan, desecrated the temples, denied the religion of the Egyptians, and changed his name to Moses.” Note the observation by Thomas Römer that the concerns expressed by Pharaoh Amenophis in Exodus 1:10, that an internal faction would collaborate with foreign infiltrators, are the same as those in the parallel text. While the chronology given by Manetho was defective, the motif of the foreign rebellion runs deep as part of the cultural memory.

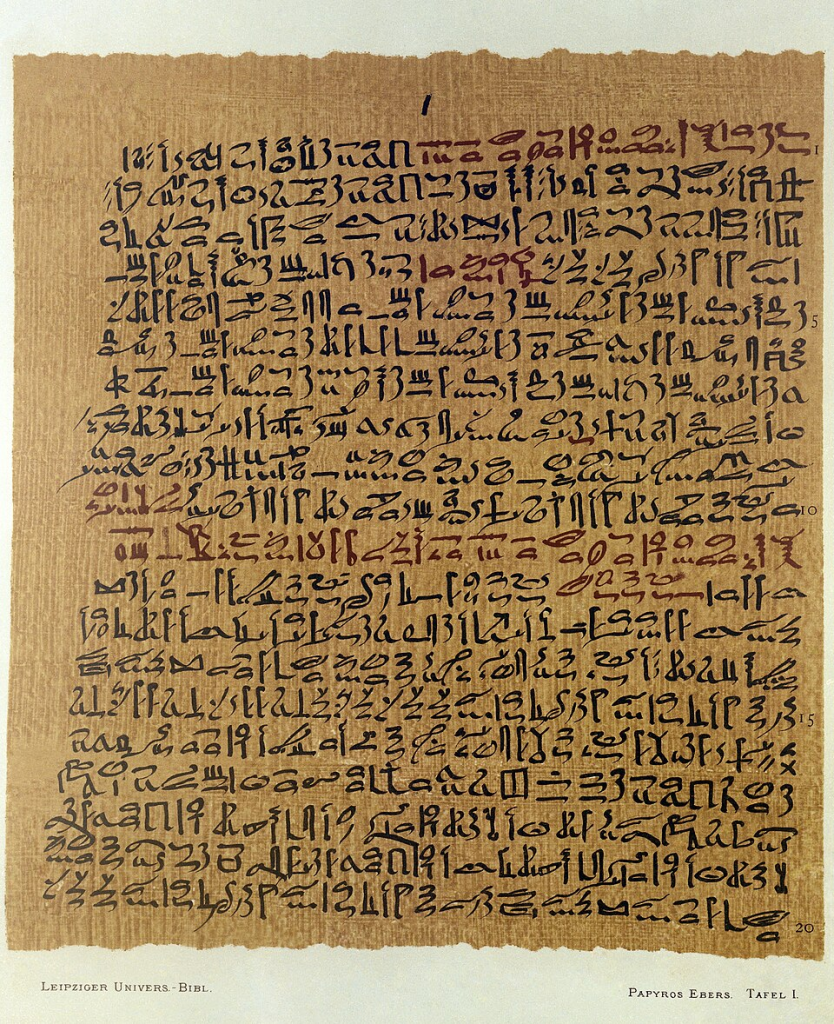

2. The Great Harris Papyrus and the Appearance of ‘Haru’

Dating back to the reign of Rameses III, The Great Harris Papyrus has documented a Levantine king, identified as “Haru,” taking over the kingdom in the wake of Queen Tausert’s death, dated about 1188 BCE. Accordingly, Haru levied taxes upon his people, abandoned the Egyptian deities, and called upon outside aid; subsequently, Haru was later vanquished by Pharaoh Setnakhte. The analogies to the Exodus account foreign aid, disregard for local deities, and final expulsion are duly striking, offering, at the least, a possible historical setting within which a historical, and hence consistent, Moses can fit.

3. ‘Flight like Swallows’ from Elephantine Stele

There is an inscription in the year two of Setnakhte in Elephantine that treats the flight of the enemies in poetic form “as the swallows depart in front of the hawk” in exchange for the payment of the Levantine mercenaries in the form of gold and silver that the enemies left behind. This motif is comparable to the passage in Exodus 12:35-36 that treats the gift of the precious materials by the Egyptians to the departing Israelites.

4. Levites as an Exodus Core

Según Richard Elliott Friedman, alginous autores señalanque en el Éxodo participaban no todo Israellites sino solo un grupo numérico entre ellos: los Levitas. Construy the tabernacle of manera semejante al carpa of guerra del Faraón Ramses II. Todo aquellos signos culturales evidenci en entonces su genuino origen egipcio.

5. Songs Preserving Separate Histories

The Song of Miriam, written in Egypt, is a jubilation of the deliverance which occurred without the involvement of the entire Israelite population, while the Song of Deborah, written in Canaan, does not include the tribe of Levi. This omission lends a measure of credence to a theory regarding the presence of Levites in Egypt contemporaneously with the lifetime of Deborah, as well as the phased inclusion of the Exodus in the national Israelite tradition.

6. Egyptian Traces in Worship

The cultural traces that appear exclusively in the Levitical texts are the importance of circumcision, the equal rights of aliens, and Tabernacle patterns found in Egypt; there is no trace of these in the non-Levitical texts. The fact that cultural traces are left exclusively in the Levitical texts implies that only the levites had lived in Egypt.

7. El and Yahweh Unification

This is when Levites settled with Israelite tribes, their worship of Yahweh synchronizing with worship of El by Israelite tribes to equal one to the other. This theological integration is achieved through texts such as Exodus 3:15-6:3, marking a significant step toward monotheism in Israelite religion. Indeed, without the arrival of the Levites, it is not impossible that a longer route to monotheism in Israelite religion would have been taken.

8. Knohl’s Military Exodus Hypothesis

Israel Knohl dates the Exodus in the year 1186 BCE and sees “on foot” and “mixed multitude” as characteristic of military forces. The Israelite leader equates Moses with the leader of the “Haru” in Egyptian sources and suggests that the Israelite leader himself did not see this as the action of slaves but of foreign soldiers who had just been defeated in the Egyptian leadership struggle.

9. Tabernacle Architecture and Egyptian Parallels

The Egyptian Egyptologist, Kenneth A. Kitchen, has cataloged how the gold-covered framework of the Tabernacle matched the parallels among earlier Egyptian temple tents, like that of Rameses II in battle. Therefore, such parallels place the Tabernacle in a 13th-century setting congruent with a Levite-led Exodus and Egyptian cultural presence.

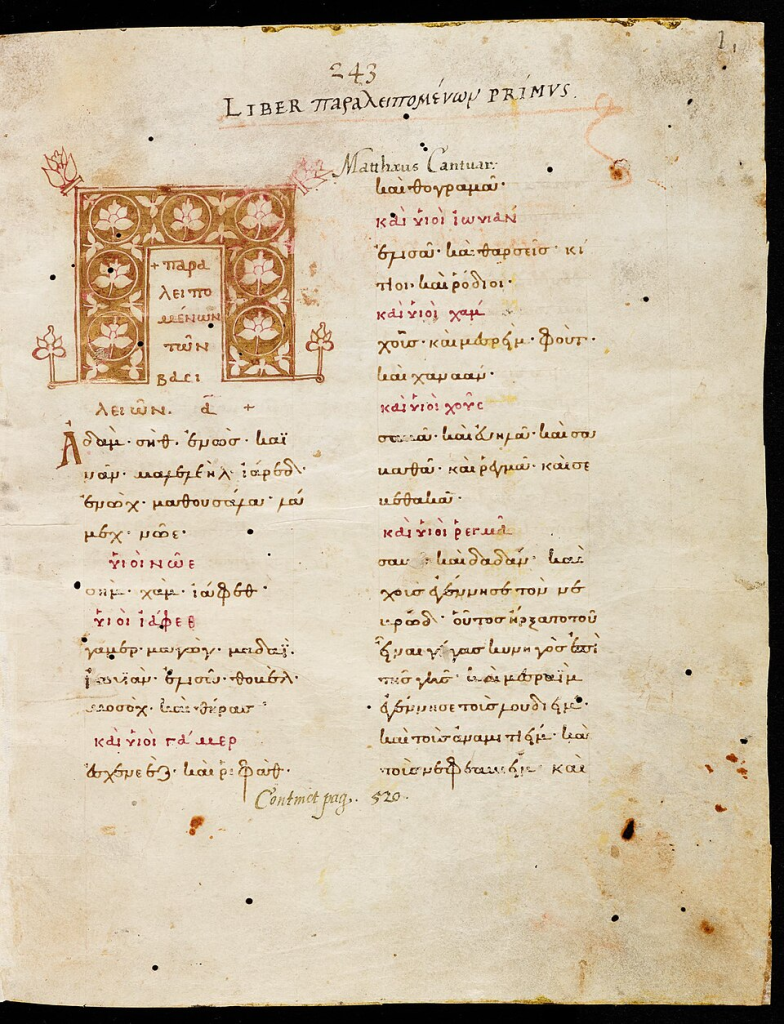

10. Didactic Monotheism of the Chronicles

The post-exilic Book of Chronicles supports the exclusive worship of YHWH by retroactively reframing the historical record to avoid syncretism. It is in this expansion of the narrative on the smashing of idols and in its omission of the stories in which the more popular kings worshipped other gods that the chronicler establishes the push for monotheism as lived practice. The Exodus as a tradition informs the subsequent format of an Exodus-shaped identity in this way and in this manner: Through such a literate fashioning of tradition, the historical impact of the Exodus tradition remains in place and in effect.

No single item, nor single text, will ever prove the existence of the Exodus, yet this set of data provides a tapestry in which historical and traditional threads weave and blend to show the tale, not of an Exodus of millions, but of a culturally different population whose Egyptian Exodus continued to shape and impact greatly upon religion, politics, and identity.