“What is the obligation of a visitor to a place that has already lost what made it famous? “In the United States, some monuments vanished in minutes or were torn down over the years, through fire, water, and the elements or through human choice that ultimately proved irrevocable. But what is left is not only the absence but also a series of lessons that trail, unobtrusively, behind the modern visitor: how cities are rebuilt, how safety regulations shift, and how “seeing the site” can slide into something more like memorializing than sightseeing. These sites were once magnets for crowds of people. The afterlife of these sites, in the form of ruins, remnants, or nothing at all, continues to shape the flow of people through the American landscape.

1. The demolition of Old Penn Station and the emergence of the need for preservation

The original Pennsylvania Station in New York was remembered for its grand public spaces, but its destruction left it with its greatest legacy. When the destruction of the station began in 1963, outrage helped spark the modern movement for historic preservation in the United States. The history of the station continues to serve as a reference point for the struggle between cities and development when “disaster” is neglect.

2. Crystal Palace, the early warning about spectacle built to burn

In 1853, an iron and glass dome appeared in New York as a tribute to ingenuity and industrya first American response to the exhibitions of the world. But when fire destroyed the dome in 1858, the rapidity of the destruction proved that the life span of novelty architecture can be shorter than expected. Even in the absence of a body count to commemorate the day, the incident has etched a lasting warning: crowd-attracting architecture is no guarantee of survival.

3. Six Flags New Orleans, where ruins became part of the itinerary

The abandoned amusement park, left over from Hurricane Katrina, was a roadside attraction for years, its roller coaster standing out for drivers, its emptiness serving as the function of a memorial. This is now being altered as the tearing down of 62 structures begins a new era for the park. The long abandonment of the park illustrates how disaster tourism can emerge without the need for an entrance fee, as the recovery of a community becomes a sight.

4. Gulf Coast boardwalks, and the economics of rebuilding “simple” places

Wooden promenades and piers formerly connected food vendors, amusement rides, and other summer activities along the Gulf Coast. While many parts of the promenades were rebuilt after Katrina, the historical boardwalk culture, developed over many decades, was not something that could be so easily replaced as the wood. The larger context is that resilience is now more a function of planning before impact, as FEMA estimates that spending on hazard mitigation yields a return of $6 for every dollar spent, a reminder that “lost attractions” are often downstream of policy decisions.

5. MGM Grand Hotel fire, and the reason smoke, not fire, redefined hotel safety

The 1980 Las Vegas hotel fire is remembered for its scope, but the most significant aspect of this incident was its architectural influence: the fire essentially stayed on the casino floor while the smoke rose, making time equal to peril. The incident was attributed to the absence of systemsno sprinklers and poor detectionand the use of combustible materials in interior finishes, which contributed to the rapid development of the fire and smoke.

6. Winecoff Hotel, and the lethal design of a single open stair

In Atlanta, a “fireproof” building showed how marketing fails when faced with physics. The route of the fire, up one unprotected stairway, made the primary escape route into a chimney. The end result was not only a different building but a different set of rules: improvements to life safety standards included enclosed stairs, self-closing doors, sprinklers, and restrictions on deceptive “fireproof” labeling. The location is still in use today under a new name.

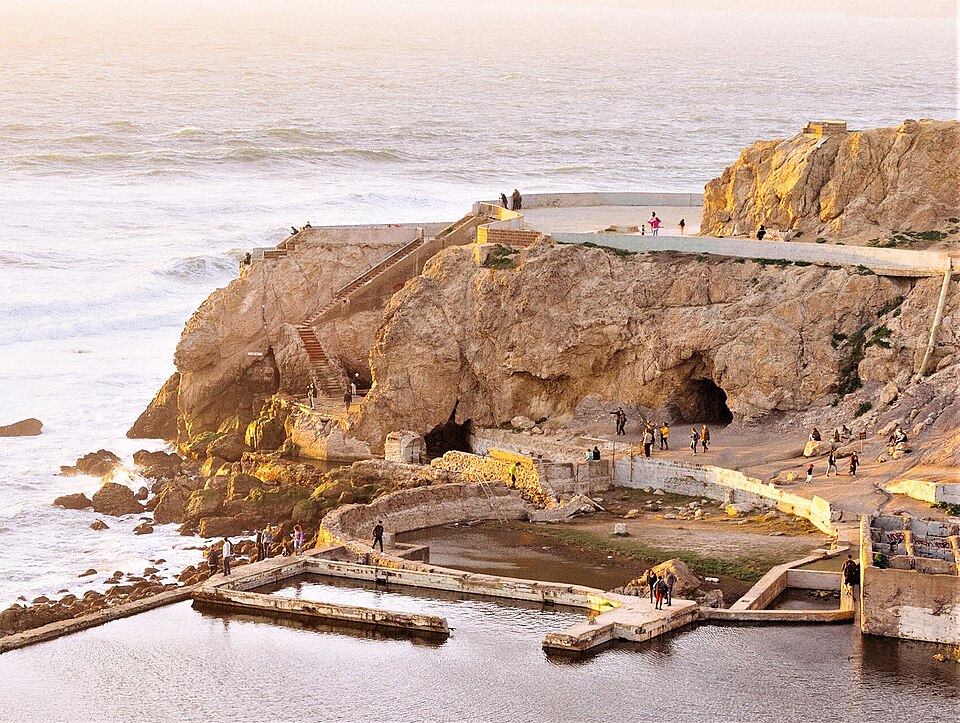

7. Sutro Baths, where recreational infrastructure turned into coastal ruins

The Sutro Baths in San Francisco were home to an unlikely amalgam of pools, slides, museum displays, and ocean vistas a constructed dream world at the edge of the continent. After a period of financial woes and a shutdown, fire claimed what was left in 1966, and the current experience for visitors is one of ruins. The attraction is one of geology and nostalgia, a testament to the fact that American monuments of leisure can be as ephemeral as the weather they were designed to withstand.

8. Luna Park’s “Electric Eden,” and the limits of early mass entertainment

In Coney Island, the original Luna Park harnessed light itself as an attraction, amazing visitors with massive electric displays and thick concentrations of wooden amusement rides. Fire in 1944 destroyed the characteristic environment of the park, illustrating how easily a city’s playgrounds can vanish when material, scale, and risk of ignition come together. Subsequent revivals might reclaim the name but not the specific cultural instan tan early 20th-century faith that novelty would always reboot.

9. The Chicago World’s Fair’s White City, built to look permanent

The 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition presented a shining vision of the city, but much of it was built with temporary materials plaster and wood modeled to resemble marble solidity. The fire of 1894 ravaged most of the fairgrounds, leaving one major structure intact. This is the quintessential American paradox: a temporary world can create a lasting influence, even if the structures were only intended to be temporary.

10. Old Man of the Mountain, and how a natural icon becomes a civic memory

The granite face of New Hampshire, an accidental “face” created by geology, gave way under the pressure of freeze/thaw cycles that had acted upon it for so many years. Its disappearance proved that loss is not merely an urban phenomenon and that it is not always preventable; sometimes the monument itself is merely a temporary configuration of stone that a community comes to regard as permanent.

The legacy of these lost sites is to train the expectations of the public. Visitors seek out plaques, remnants, overlooks, and interpretive context not only for the purpose of entertainment but also to learn what a site has endured and what it has learned. In this respect, the lost attractions of America are still active participants in modern life. Their loss continues to influence building regulations, coastal development, and the tacit ethics of visiting what is lost.