A first-century Jewish teacher does not tend to bequeath a signature, a diary, or a portrait which has been authenticated. But Jesus of Nazareth is at the middle point of an evidence riddle that continues to draw both archaeologists and historians, partly because so many subsequent legends are determined to prove that his life had its roots in reality officials, reality towns, and reality outcomes.

Whether one object proves Jesus is seldom of use. It is the way the various types of traces, stone inscriptions, settlement remains, hostile graffiti, and the history of outsiders, can be integrated into a world where someone like Jesus can be fitted in, without having to appeal to devotion.

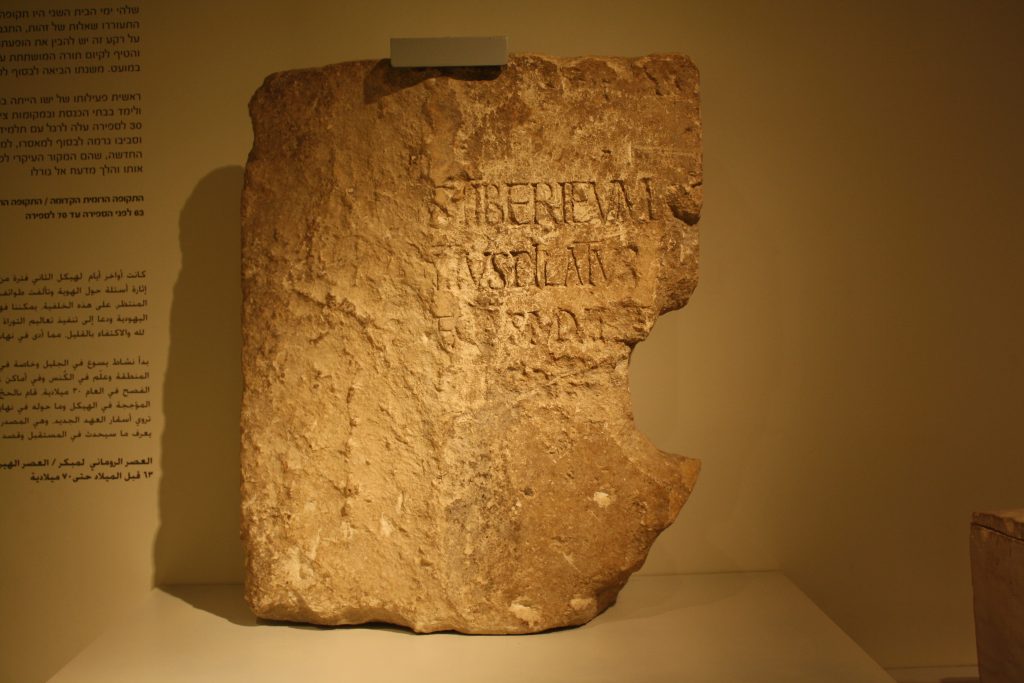

1. A stone inscription that pins Pontius Pilate to history

The name of Jesus is not the strongest name check in this story. It is the inscription on the Pilate Stone which is a fragment of a dedication by Caesarea Maritima that mentions the name and title of Pontius Pilate as the prefect of Judaea. This is important since the Gospel accounts place the execution of Jesus under the jurisdiction of Pilate and it is this stone that solidifies that character within the administrative realm of the Roman Judea. In itself, a trial scene cannot be checked by an inscription. What it is able to do is eliminate the concept that Pilate is part of scripture. It narrows down the historical perspective where a crucifixion during a Roman rule emerges as a common form of imperial violence, and not a fabricated setting.

2. A town with first-century footprints: Nazareth

Discussions of Jesus tend to become geographical: was there a Nazareth as had been described, or was it added to a religious map later? The remains of small houses, farm equipment, and other signs of everyday work found during excavations in the contemporary city indicate that Nazareth was inhabited during a time within the time frame of the assigned childhood and early life of Jesus. Such evidence does not refer to a particular resident. It does something more fundamental and more significant to historical practice: it confirms that the setting is credible and is not an anachronism of invention, and makes the gap between story and landscape even smaller.

3. A Roman historian who treated “Christus” as a punished person

The tone in most refers to minority movements by Roman writers can be very informative, as they are rarely sympathetic. In book 15 of Tacitus in his annals, the historian mentions that Christus was punished with the utmost cruelty by Tiberius, that at the hands of Pontius Pilate. This value is neither theological nor historical, but an administrative one: a Roman writer locates the name of the movement in an ostracized founder. Even the brutal punishments that were applied towards Christians in Rome were reported by Tacitus, and this serves as a social reality check as to how fast the tag of Christian became visible enough to be attacked. The text does not recreate the life of Jesus, but the origin narrative is put into the context of Roman memory and recordkeeping of the population.

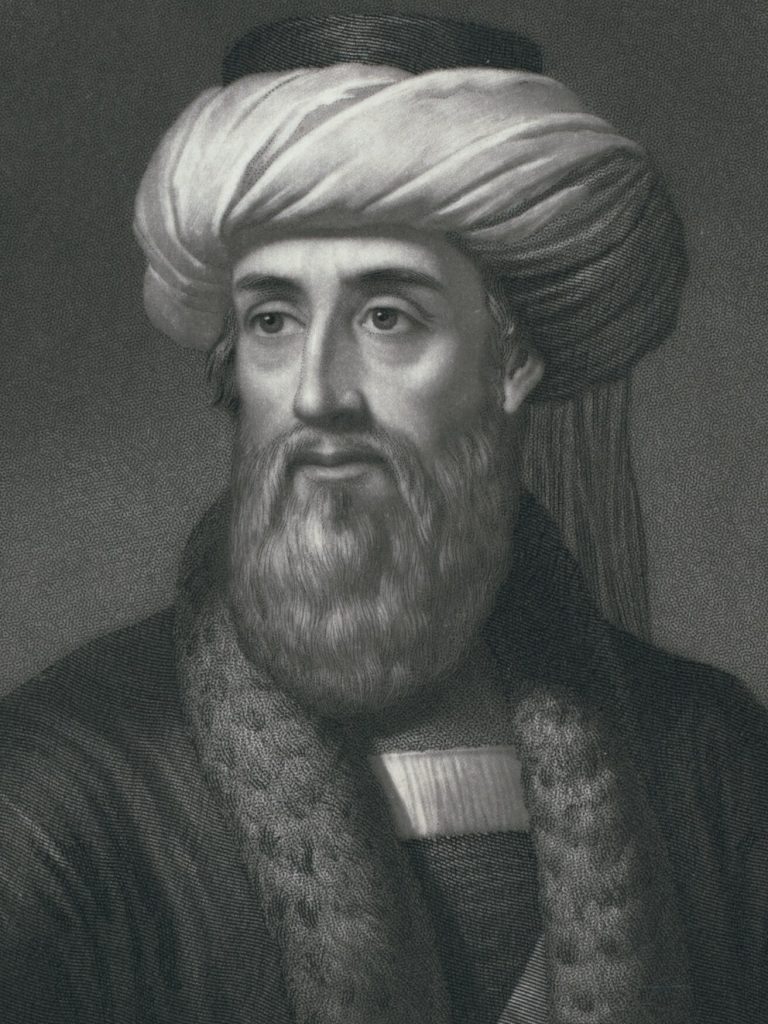

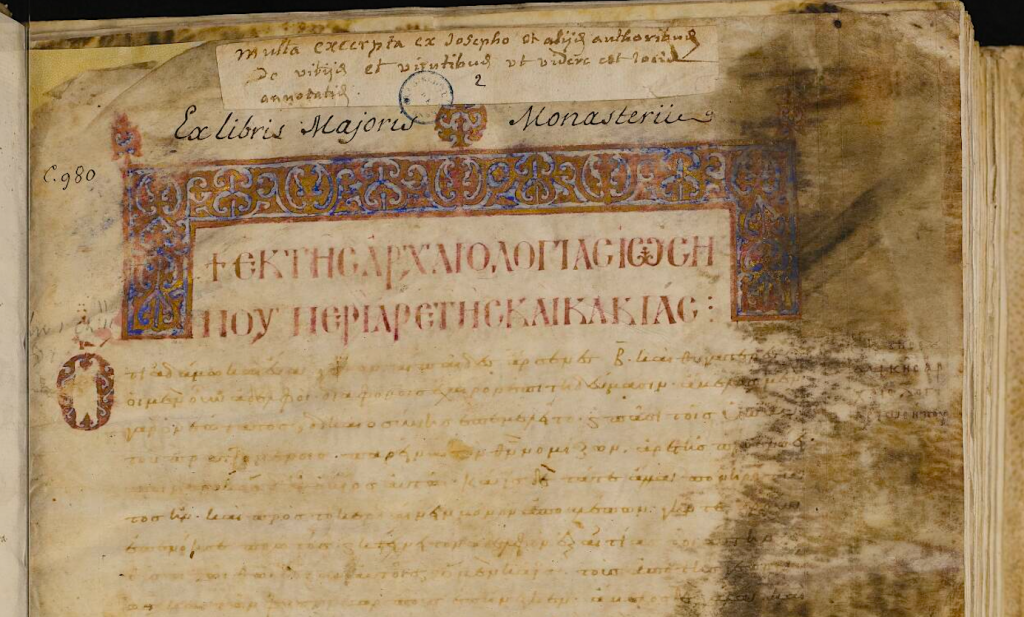

4. Josephus and the problem of a paragraph that refuses to go away

In the late first century, Flavius Josephus wrote and refers to Jesus in the Josephus book Jewish Antiquities, with a controversial paragraph called the Testimonium Flavianum. It is not how much part of the paragraph is true, but how much is an echo of Josephus, and how much is an enhancement of the text by copying. Recent criticism has pointed out that certain manuscript traditions do not read He was the Christ, but, as it makes more sense as the expression of a non-Christian Jewish historian, thought to be the Christ.

Even where wording is controversial, the recurring heart is historically helpful: Josephus finds Jesus in a familiar struggle between the elites and an orthodoxy-popular teacher, and he ties the tale to Pilate and to the community which still bore the name of Jesus.

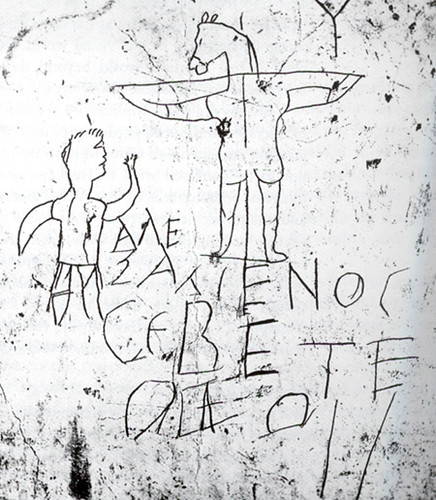

5. A mocking graffito that implies a target already existed

Not every trace of the early is the religious one. The Alexamenos Graffito (normally dated circa 200 CE) features an ugly, slanderous depiction of a crucified figure with the head of a donkey and a label stating worship. It does not record the life of Jesus, but it does show that non-Christians perceived it as a people who worshipped a crucified man- and that this should have deserved ridicule in a Roman setting.

Vile satire is no argument to biography. It is an indicator of cultural awareness: a movement, a scandalous center of it was there enough to laugh at.

6. The Shroud of Turin: a powerful object, an unsettled scientific story

The Shroud of Turin, a lengthy linen cloth with the faintly drawn image of a wounded man is no artifact that can be more fascinating. A broad scholarly aversion to dating the cloth as first-century evidence was influenced in part by the late 1980s use of radiocarbon dating of the cloth to the medieval period. The argument is however still alive since the formation of the image of the shroud can hardly be convincingly reproduced and some of the researchers claim that the radiocarbon analysis may have been distorted by contamination. The most recent campaign to re-sequester the dating is whether the presence of carbon monoxide pollution may cause the apparent age to differ by a significant margin under some circumstances. The draw of the shroud is obvious: it condenses violence, burial tradition and iconography into one surface. Traditionally, though, it is a disputed object instead of a ground pole.

All these hints do not work as a modern ID card. The combination of all these suggests why the question of whether he was real continues to fall on the same response, namely the surrounding cast, places and initial references to outsiders, are more in line with a real man who was executed and subsequently recalled, debated, sneered at and written about not just in Judea, but well beyond its boundaries. The tougher one has never been as to whether or not there was a man. It is the way the death of a man was turned into a tale more potent enough to leave the marks in stone, ink and human manners till the 2000 th anniversary.