The most legendary gunfighters of the Wild West continue to travel to this day in both person and legend, both the history of a person, and the legend of a legend. The difference is important, as gun skill is not always described by the legends as much as by reputation, print culture, and the nervous system of frontier towns.

Even Wyatt Earp, who was often portrayed as a lawman with no bending, had left behind him a reminder that the triumphing hand in violence was usually the withholding and not the flashing one. The man who did it slow was the one who won the gun play most. The West which created such a line was noisy with rumours, authoritarian with local policies and bloodthirsty after bigger-than-life figures.

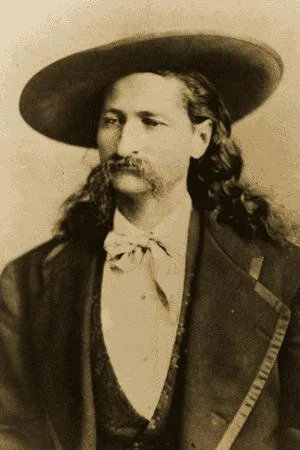

1. Wild Bill Hickok

James Butler Wild Bill Hickok, a scout and a lawman in his youth, rose to fame because of the duel that hardly resembled the film fighting action. In the year 1865 he challenged Davis Tutt in Springfield, Missouri and fired about 75 yards away carrying a Colt Navy on his forearm. The range, and the long patience it demanded, made the engagement one of those few quick-draw-type duels which historians keep going back to. The fame of Hickok rose when newspapers and dime novels transformed violence into entertainment, followed by another growth in 1891 when he joined the show by Buffalo Bill. The finale was at Deadwood in 1876, when he was shot in the back in poker, when the Dead Man’s Hand was a cleaner version to a sloppier living.

2. Belle Starr

Myra Maybelle Shirley Starr is not remembered so much in terms of isolated spectacular robberies but in terms of the network of individuals surrounding her outlaws, family connections and the postwar borderlands where association was currency. Her portrait, variously pictured in black velvet with plumed hat, actually worked: it rendered her instantly recognizable to an audience accustomed to decipher costume as character. The 1889 murder in front of her Oklahoma home never took shape into a definitive answer and that ambiguity became part of the propulsion of the narrative. Subsequent versions became so embellished that biographer Glenn Shirley remarked that she was swollen into a national archetype within a short period of time despite a lack of evidence. Even after more shootouts were confirmed to be false, the open ending is what kept her alive as Bandit Queen.

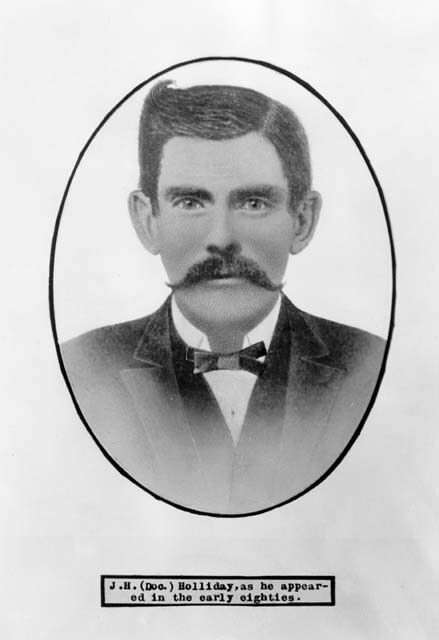

3. Doc Holliday

John Henry Doc Holliday went to West with two identities in hand; as a trained dentist and a professional gambler. Once tuberculosis had redefined his future, he passed through the frontier towns, where a pair of rifle-cold eyes and a pair of chilled heads might be violence enough.

His friendship with Wyatt Earp put him at the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral in 1881, an incident that was mythologized later, but which was said to have lasted roughly 30 seconds. The legend of Holliday lives as long as sickness never suspends the drama; it makes it stricter. In 1887, at the age of 36, he passed on leaving a portrait of twerk and sternness stamped into the same frame.

4. John Wesley Hardin

The story of Hardin, son of a Methodist minister, has long been tempting the author to make him a morality play. The record however indicates a young man molded by post war Texas who adopted the use of violence at a young age and declared his first kill at the age of 15. Hardin was proud that he had killed over 40 men, although many historians put the probable number at about 20. Having been captured in 1877 he served 17 years of a 25-year sentence, law-studied, and made an attempt to join society with a new professional mask. The mask failed: in 1895 he was shot in the back of the head in an El Paso saloon, a killing that echoed the theme of the frontier that reoccurred inexplicably danger which came outside the frame of the usual understanding.

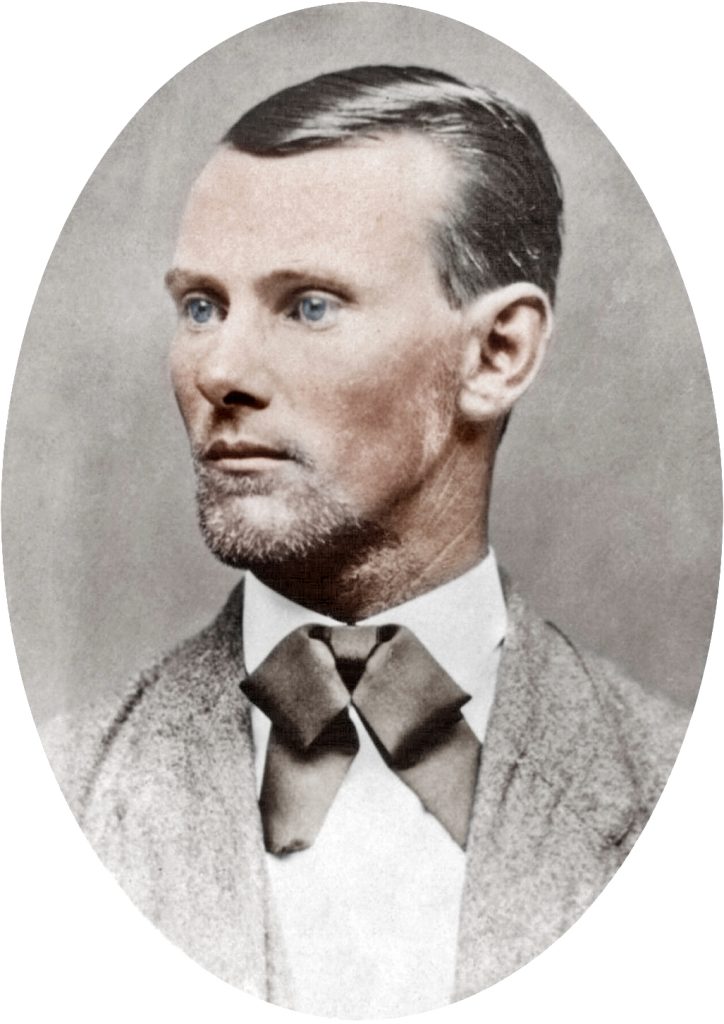

5. Jesse James

Jesse James would never have created a folk figure because his crimes were especially generous, but merely because the divided people allowed him to be a hero. An ex-Confederate guerrilla, he headed the James-Younger Gang in an attempt to rob banks and trains which the newspapers reported such that their attention bordered on admiration. He was able also to create his own myth. James in his letter published by the editor John Newman Edwards, compared himself with conquerors and emperors, when he wrote: We are not thieves, we are bold robbers. The line explains how it happened: not notoriety was a by-product but an instrument. James was murdered by a man called Robert Ford who was in his circle which made betrayal the last act in a story he had assisted in creating.

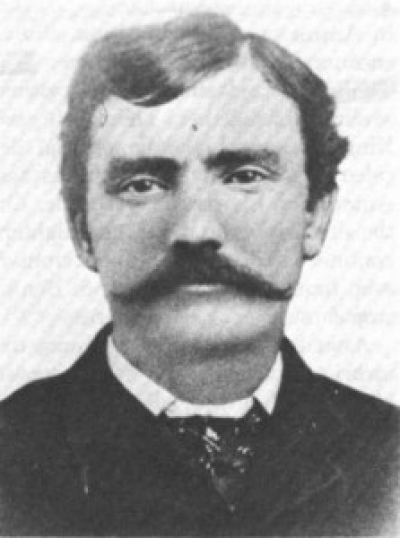

6. King Fisher

The reputation of John King Fisher was more based on charm than gunplay. He stole cows, he practiced a rather gallant exterior, and he was even a part-time lawman a system that was well adapted to the realities of a world in which the distinction between power and expediency might be twisted to suit the demands of local conditions. The popularity of frontier violence indicates a lesser-known fact by Fisher: It was not always lynch law, but rather social lynch law. He was ambushed to death in 1884 in San Antonio, a circumstance that did not consist of that kind of a fair fight that later entertainment offered.

7. Billy the Kid

Henry McCarty, or William H. Bonney, was made a popular youth, and youth was too enticing to narrators. Being the orphaned young and lured into robbing, he joined the Lincoln County war, a conflict that demonstrated the way local power might cluster around cattle, trade, and authorities, as well as around ideology. The number of killings he had was a promotional tool. He had 21 deaths; some historians have contended that the number must be much less. He was killed by Sheriff Pat Garrett in 1881 after he had been arrested and made a dramatic escape out of custody killing two deputies a denouement which, to many viewers, was more like a book thrown open than a book closed, an invitation to the business of souvenirs, reenactment, and debate.

8. Tom Horn

Tom Horn represents a different category of frontier gunman: the hired tracker whose violence served economic power. In the late cattle wars, he worked for wealthy interests to hunt suspected rustlers, operating with the credibility of experience and the moral murk of contract killing. Horn was convicted and hanged in 1903 for the murder of 14-year-old Willie Nickell. The case remains debated in popular memory, but the larger significance is clearer: by the turn of the century, gun skill often attached itself to labor disputes and private enforcement, not simply personal feuds. Horn’s story shows the West sliding toward modern structures of power corporate, legal, and brutal.

These figures endure because each life offered more than gunfire: a costume, a phrase, an unresolved death, a betrayal, a public role that shifted between outlaw and lawman. The “Wild West” that survives in memory is built from those portable elements. Strip away the staged noon duels and the mythic precision, and the remaining stories still hold less as celebration, more as a record of how violence, media, and reputation braided together on an American frontier that was never as simple as the posters promised.”