The Exodus story manages to live through the fact that it is located at the cross-road of memory, identity, and landscape. A common complaint that stops the modern discussion is this: no one inscription tells of an Israelite leaving Egypt.

But archaeology seldom addresses itself in assertions. It talks in aisles and warehouses, in vernacular names, in poems having an eternal memory. A read between Egyptian writings and biblical language (and reading border infrastructure) makes the argument less a question of proof and more a question of whether two or more, independent facts are pointing to a possible historical background.

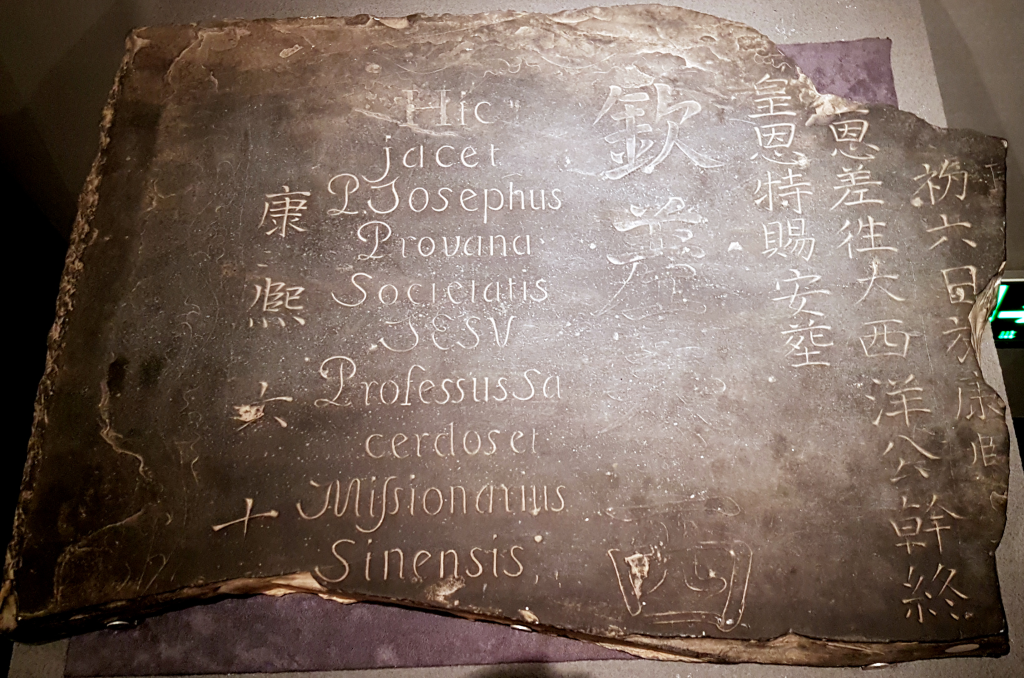

1. A revolt tale where a leader “took the name of Moses”

Among the most controversial parallels to Exodus is one by an Egyptian historian known as Manetho who wrote an account surviving in Josephus. A priest by the name of Osarseph in his story heads an internally marginalized community, allies with foreigners, and opposes the Egyptian religion, and ends up being expelled. That repetition of lines that attracts attention is the line that Osarseph took the name of Moses.

However polemical the aim of whatever story may have, it maintains an Egyptian form of memory of turmoil that is associated with strangers and exile a resonance that is more difficult to deny when read along with the theme itself of Exodus of a feared inner people in agreement with outer powers.

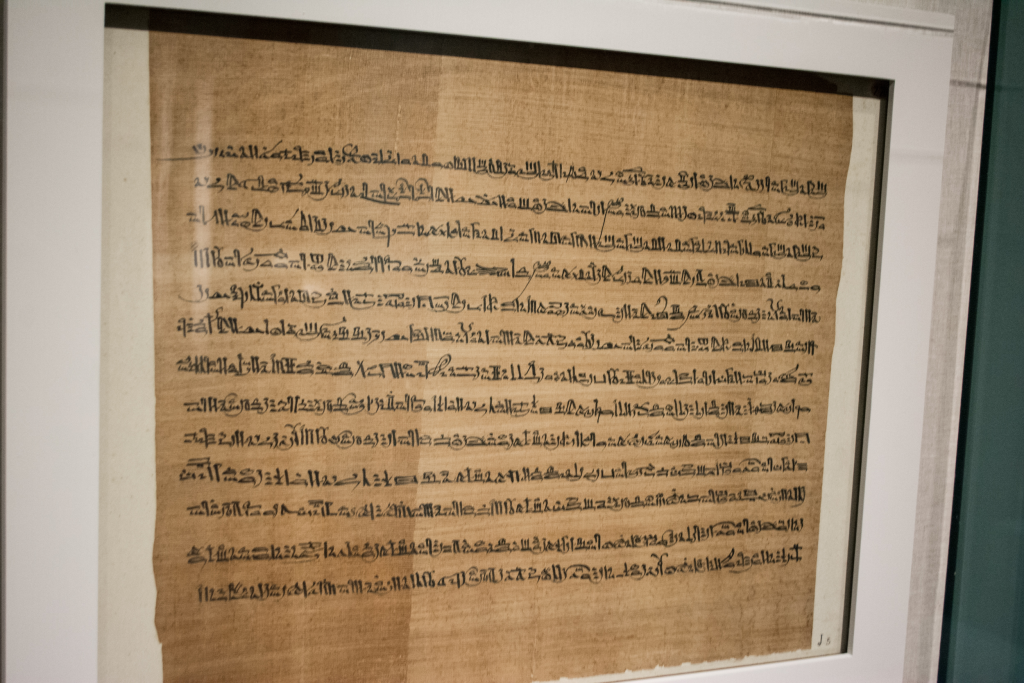

2. A papyrus describing a foreign “irsu” seizing power after a queen’s death

The Great Harris Papyrus, a large one of the great Egyptian documents, talks of chaos after the death of Queen Tausert and the emergence of a usurper leader of foreign descent. The passage illustrates someone who opposes the deities, mining resources, and invoking external assistance then cracks down and pushes out by Setnakhte.

Exodus is not directly confronted at the same point and thus is not exactly the same number of characters up against each other, but a familiar formula: internal unrest, foreign-linked leader, and a narrative of cleansing restoration. It provides a relatively historically rooted pattern of the Egyptian sources explaining disorder on the eastern border.

3. An Egyptian monument describing enemies fleeing “as the swallows depart before the hawk”

At Elephantine, a monument of the second year of Setnakhte, employs an image of the enemies, scattering rapidly as the swallows fly away before the hawk and says that valuables had been left behind, when the swallows fled. Exodus notoriously contains the departure with gold and silver, as a melodramatic exchange of fortune at the border of escape.

The resemblance is not a technical one. Nonetheless, once there is a unique motif, the one of fearful flight bound to valuables, present in royal Egyptian rhetoric and Biblical memory of liberation, it becomes one more tessella in a greater mosaic.

4. The “Sea of Reeds” problem that changes the map

In Hebrew the water traversed is yam suph it is better translated by Sea of Reeds than Red Sea. The importance of that translation change is that the reeds are an indicator of marshy lake land and not the open gulf waters.

Studies associated with the eastern delta of Egypt point to the fact that the ancient Isthmus of Suez had numerous lakes and canals, which were radically transformed by the present day engineering project. Where, the word reeds has a less poesied effect, and is rather geographical than poetic pushing the discourse toward the lakes of the delta, like the Ballah Lake, than the one modern shoreline.

5. Fortresses on the eastern road that explain why a direct route was avoided

Exodus asserts that the parting party failed to use the direct coastal road to Canaan. The topic of Egyptian archeology has shed more and more light on what that road involved: a fortified line of defense consisting of forts and military camps that were designed to regulate the movement along the border.

One of the recently uncovered fortresses in the northern Sinai depicts the size of this system, with thick walls, towers and internal infrastructure, with a garrison estimated at an average of 500 soldiers (the garrison was probably 400-700 soldiers on average). Regardless of the date one dates Exodus, this confining fact provides a permanent logistical understanding: the easy road east was the most disciplined as well.

6. Pi-Ramesses as a real city with a short, revealing lifespan

Raamses in the bible is commonly correlated to Pi-Ramesses who is the capital of the delta linked to Ramesses II. Archeology dates it to Qantir and its history is unusually particular, the city having prospered during a short period, then declined when a branch of the Nile had become dry and the major part of its stone was transported to Tanis.

The fact that its lifecycle is compressed, meanwhile, makes the site useful in terms of chronology and editorial updating, how one can discuss earlier events using a later place-name without creating an impression that the event in question happened at the time the name became well-known. Pi-Ramesses reads like less of a gotcha and more of a study of the way ancient writings dealt with geography with time.

7. The Levites as a smaller Exodus-shaped memory-bearer

Scale is one of the most far-reaching interpretive changes. Instead of creating a complete picture of a people on the move, part of the scholarship contends that a smaller group, commonly linked to the Levites, brought with them into the emerging Israeli tradition a lived Egyptian experience. The purported fingerprints contain Egyptian-style names, circumcision accent, and tabernacle information that would appear to be the Egyptian military and ritual types.

Combined with early biblical poems, the sequence will be suggestive the Song of Miriam glorifies deliverance without explicitly mentioning all of Israel, whereas the Song of Deborah does not mention Levi. Taken together, all these silences create space to a memory, which started with a subgroup and subsequently expanded to national identity.

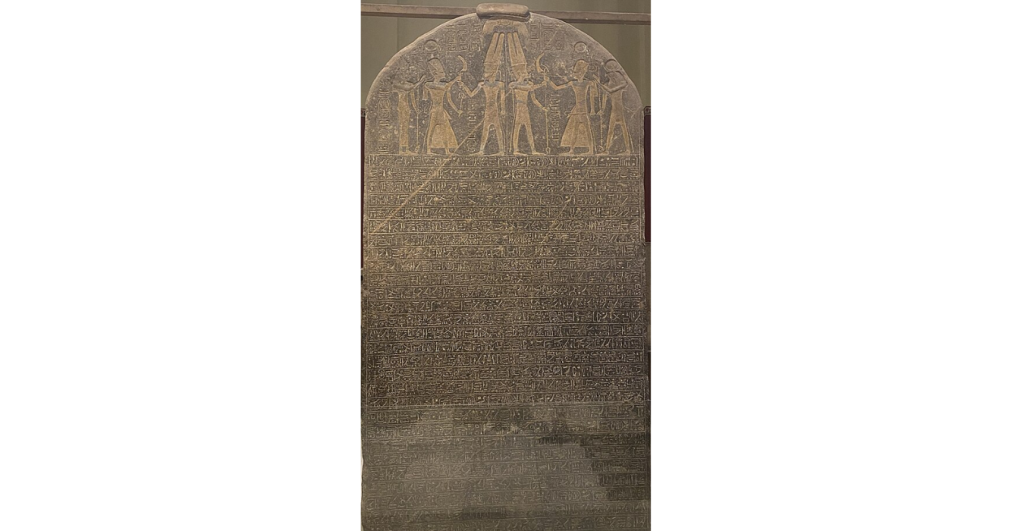

8. A contested hint that “Israel” may appear in Egypt earlier than expected

The most famous Egyptian inscription mentioning Israel is the Merneptah Stele of circa 1205 BCE. However, a possible earlier mention has been suggested by some scholars, which may be around 1400 BCE, on a broken statue pedestal with name-rings, although the interpretation is controversial (placed the reading nearly 200 years earlier).

Although the assumption that the Egyptian record is disjointed is a disputed one, it does bring up a significant fact to the layperson, namely that first mentions may move when neglected objects are revisited or re-considered.

No artifact puts the Exodus into one and simple historical snapshot. Even the more powerful instance is cumulative: Egyptian histories which keep the ways of expulsion and disturbance, border regions which are better negotiated by a crossing of reeds than by an open sea, internal indications of the Bible that suggest the existence of a people whose memory is carried by special people.

In that light, the Exodus question remains open in a productive way less a courtroom verdict, more a continuing attempt to map a story onto the stubborn, changing ground of the eastern Nile world.