One shred of writing does not often resolve an ancient question. It is the manner in which individual hints start to cog in the same direction that changes minds, gradually, and that is a place-name that was in existence during a particular period, a phrase that echoes with the experience that was recalled, a fortress that reveals why one path was not taken.

The Exodus occupies that uncomfortable geography where archaeology, writing and cultural memory meet. The Egyptian royal inscriptions were made to glorify kings, not to maintain embarrassments, and the Nile Delta, with its eastern part wet, built over, and heavily farmed, has not been generous with archives. Nevertheless, there are one or two sources and site facts that continue to resurrect the discussion since they strike the pressure points of a story origin, setting and the possibility of leaving the borders of Egypt.

1. Osarseph of Manetho, who is a priest and turns into Moses

Among the most peculiar parallels deserves the Egyptian tradition which was recalled in subsequent literature. In his preservation of Manetho, Josephus narrates a marginalized group that is labeled diseased outsiders, rebels and unites with foreigners who are affiliated to Canaan and are eventually pushed out. The author is a priest called Osarseph who, in the climax of the story, changes his name to Moses.

The description is not a point-by-point correspondence of the story in the Bible but the frame is hard to overlook: internal fear of a persecuted people group in correlation with the external enemies, religious war, and a forced migration. It is the type of mangled recollection which is able to endure centuries which is familiar in a sketch even when its borders are bevelled to stinging.

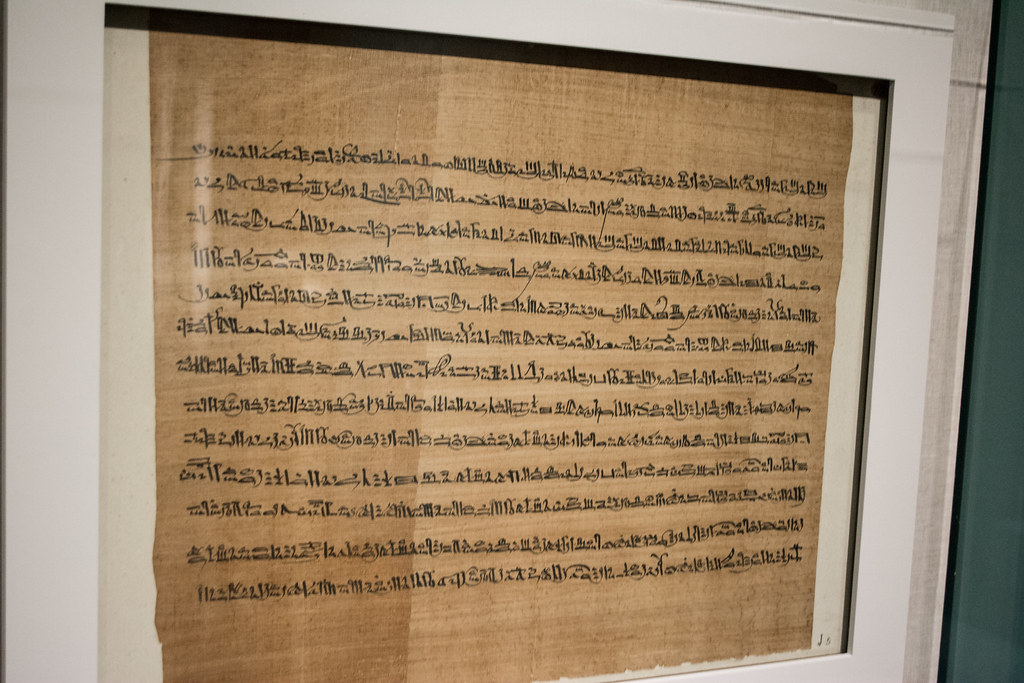

2. The Great Harris Papyrus and a foreign Haru in time of political discontinuity

The same is occasionally caught in its records, of Egypt itself–where a new pharaoh wishes to emphasize the chaos that came before regeneration. The Great Harris Papyrus is an account of turbulence following Queen Tausert, with a foreigner, the irsu, of the name Haru taking over power, disrupting cultic existence, and recruiting followers, before being overcome, and his followers eliminated.

To Bible readers, the hook is not one of actual identity but the form: a disturbance of Egyptian Delta world, intertwined with foreignness, and then an expulsion story. It provides the reminder that there were periods when Egypt experienced foreigners in the northeast Delta being considered as a threat to order.

3. An Elephantine monument, which talks of enemies running like swallows

The second-year monument of Setnakhte on Elephantine employs a most graphic image a foe goes away And doth the swallows fly Before the hawk, And leaves a treasure by. The importance of the poetry lies in the fact that departure as an exit with valuables is also seen in Exodus, but that these valuables were carried with them in the form of gold and silver on the moment of departure.

Literary echoes cannot establish that any of the events took place, but they demonstrate the possibility of Egyptian victory language and Israeli departure language circling around the same themes, panic, flight, wealth being shifted in a border moment.

4. The city of the biblical name Rameses was a royal Delta city

The Rameses of the Bible has been operating a long time as a dating trigger, shifting some reconstructions into the Ramesside. Digs at Tell el-Dab‘a, however, make any easy formula between the biblical name and one century difficult. The site has a long history, passing through Rowaty, Avaris, and Perunefer, to the late Ramesside capital.

Another physical setting that suits a Delta in court life and administration is an archaeological work that discovered a large palatial precinct in the area. The most important fact that the reader needs to understand is that the word Rameses in the text may be a common name of the location that previously existed under other names, but not a time-stamp.

5. How Egyptian records may be silent and yet not decisive

The main basis to skepticism is frequently a question, why should a civilization as literate as Egypt not mention Israel in Egypt or a mass exodus? One of the replies refers to the character of what endures. Archaeology has not provided a particularly rich documentary archive in the northeastern Delta–the region with which most to do with the biblical setting can be identified. It is not just the subject matter that scribes decided to write about, but what the mudbrick cities and the waterlogged ground and the subsequent building activity could sustain.

In that regard, the phrase of absence of evidence is no evidence of absence, is a phrase that descends to less of a mantra than a topography: there are places where triumphal stelae are preserved; there are places where paperwork is virtually swept away.

6. A landscape constructed of reeds and the Sea of Reeds

The Hebrew word meaning the crossing is not Red Sea, but yam suph (Sea of Reeds), a name which was later translated in a manner that led to the evocations of open salt water. Instead, Reeds gives an example of marshlands and lake networks and the eastern frontier of Egypt used to have a chain of fresh water lakes and canals that extended across the Isthmus of Suez.

Studies that put emphasis on this context portray the rationality of a border crossing: the west is as cultivated Delta, the east is desert. The way also describes why an open road made along the coast, reinforced and patrolled, would have been avoided, and forced the passage was made toward a barrier of reeds, which served as a natural frontier.

7. Place-names which cluster during the Ramesses

Names are some of the most powerful indicators that the date of the Exodus was later than they are indicated to be. A custom which recollects Pithos, Ramses, and the sea passage with marks which are identifiable with Egyptian toponyms can maintain an actual historical horizon. A school of thought focuses on the fact that these names are seen consecutively in Egyptian materials during the era of Ramesses, implying that the tradition of the Bible kept the genuine geographic memory during that time.

According to this perception, the story of the Exodus has a map based on experiential knowledge- although the event that transpired behind the memory is controversial.

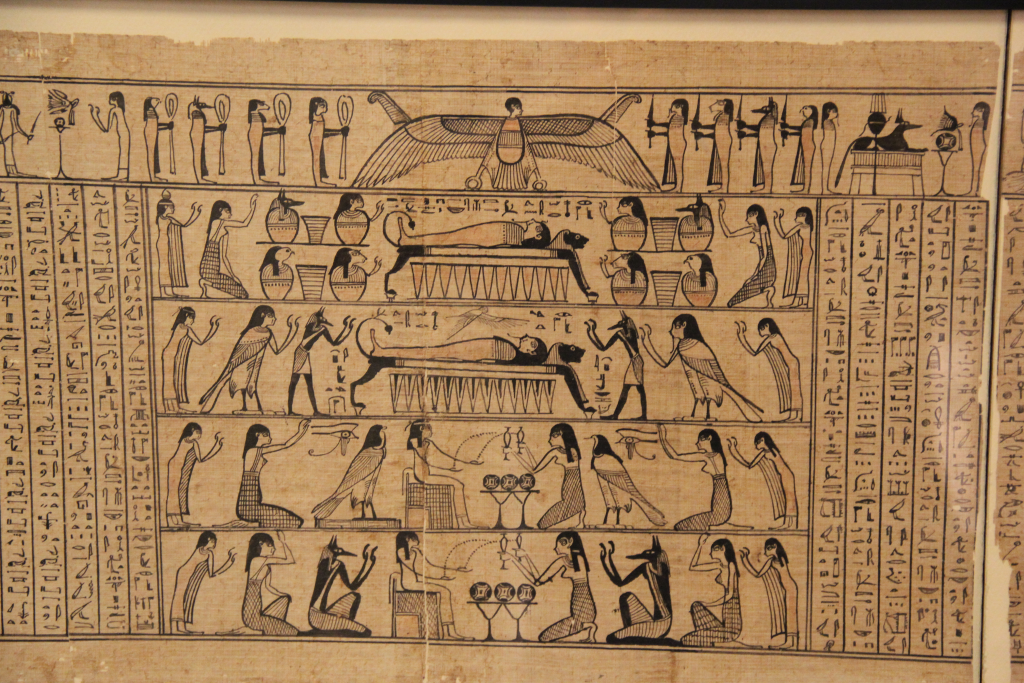

8. Egyptian writing, Isis: the Merneptah Stele, and a previous possibility.

Beyond the question of the Exodus, the broader context of history is important: at what point, in Egyptian history, does Israel even exist? The Merneptah Stele has frequently been pointed to as the first secure extrabiblical mention of Israel, locating a people named Israel in the Canaan by the end of the 13th century BCE.

Simultaneously, other researchers have contended that there may be a potential reading of a broken statue pedestal of circa 1400 B.C.E. as to Israel. The reading is controversial, yet its existence demonstrates how a single name-ring may revert the chronological shutter, and why the origins of Israel and the dating of a tradition of the Exodus have continued to go hand in hand.

9. The Levites as a smaller Exodus memory-bearer

Not all models require a vast migrating population. One influential proposal argues that the Exodus tradition may reflect the experience of a smaller group often linked with the Levites whose Egyptian cultural traces were later woven into a broader national story. The details used to support this include Egyptian-style personal names within Levite lineages and cultic features that appear more strongly in certain biblical strata than others.

This approach changes the question from “Where is the debris field of a nation on the move?” to “Which group carried a memory powerful enough to become Israel’s origin story?”

No single object “proves” the Exodus, and the sources do not speak with one voice about date or scale. What they do supply is a set of recurring anchors: a Delta world where Semitic populations lived and labored, a reedy frontier that functioned like a wall, and textual traditions Egyptian and Israelite that preserve the shape of conflict and departure.

That mosaic keeps the debate alive because it shifts attention away from one missing smoking gun and toward a more archaeological kind of realism: the past survives in fragments, and sometimes the fragments still point to a path out of Egypt.”