The story of the Exodus has always occupied an awkward position The story of the Exodus has long inhabited an uncomfortable niche: radically described, passionately remembered, and stubbornly resistant to being located to a single trench.

What has developed over the past few years is not the emergence of a new, abrupt piece of evidence, but the expansion of a series of points of contact, Egyptian literature, border resource, name patterns, and older layers of the bible, to be discussed as having been constructed out of actual material and actual institutions. To the material record remains to be added the gaps, but now they lie next to sharper points of contact.

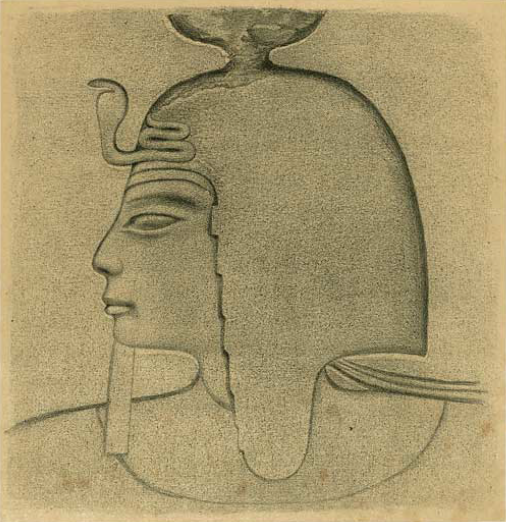

1. Manetho and his rebel-priest who was Moses

According to a text preserved by Josephus, an Egyptian historian, Manetho relates an uprising of a renegade priest called Osarseph who became known as Moses. A band of outcasts, confrontation with Pharaoh, a coalition with outsiders, and eventual exile, the plot repeats key themes of the central story of Exodus but with no similar parallelism. The worth of this is not that it is exactly on pitch; but simply that an Egyptian literary tradition had retained a remembered scheme of intestine crisis identified with foreigners and a ruler refurbished with the name of Moses. Nonetheless, critics who are skeptical of the usefulness of Manetho are aware that such accounts can be useful in preserving older cultural memories in a distorted way, particularly when writers are creating identity and recrimination.

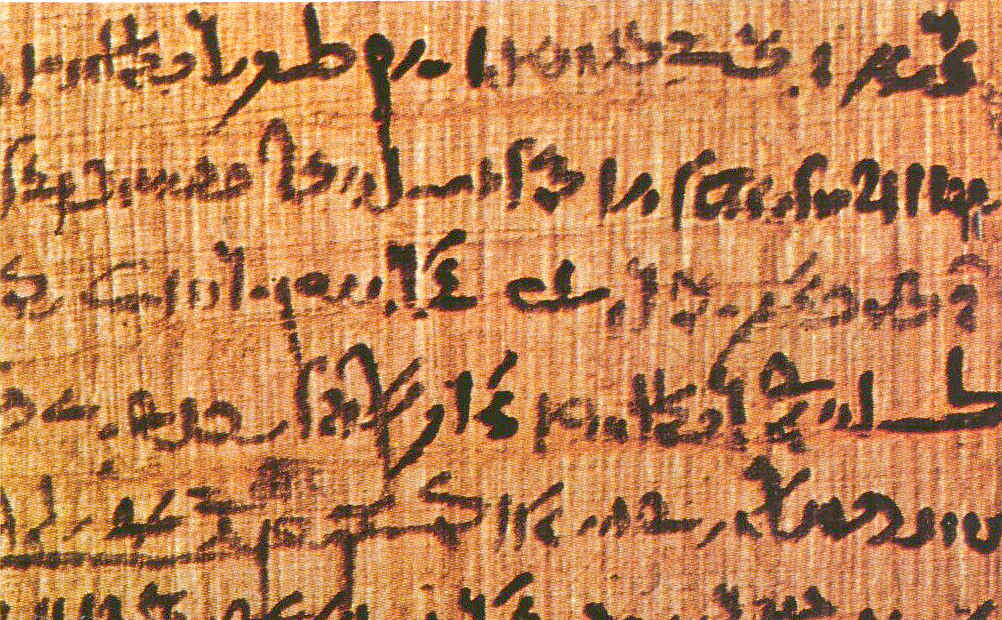

2. A papyrus about a foreign powerful man and a nation that is going through trouble

One of the most famous long historical papyri, the Great Harris Papyrus, describes a disorganized Egypt following the death of Queen Tausert and how a ruler of foreign origin an irsu joined with a name “Haru” took over and disrespected Egyptian religious order imposing levies. The episode is completed by the restoration story of Pharaoh Setnakhte which incorporates punishment and elimination of the architects of the disorder. The allusion to the theme of the book of Exodus is not literal: the fear of foreigners, social and political disintegration, and political-theological restructuring. It is important since even Exodus is a political-theological memory which is more shaped by meaning than by chronology.

3. One line, rhymed, tells of enemy flying away, like swallows, and leaving treasures

In one of the Elephantine monuments dated during the reign of Setnakhte, the enemies are reported to leave on the departure of the swallows before the hawk, and leave their valuables behind them. The expression is interesting as Exodus retains its own graphic scene of departure where people who depart with gold and silver. The parallel does not demand identical group, identical year, identical passage, but it emphasizes the similarity of the motif used in Egyptian royal texts and the biblical tradition to illustrate a society that was fracturing along its borders: panicked flight, abrupt reversal, change of fortune.

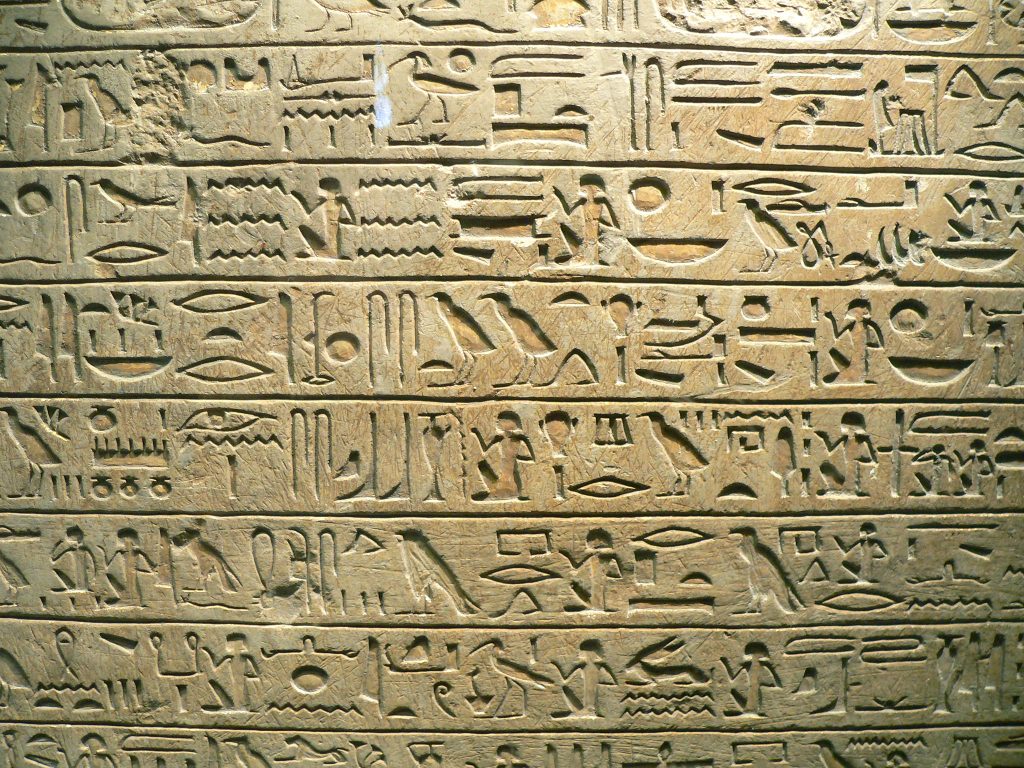

4. Egyptian fingerprints of names and ritual life and the concept of the Levite core

A reason that has increased staying power is that the memory of the Exodus might have been imported into the tradition of Israel by a smaller segment of the population and not a whole population flow. In this opinion, Levites bear telltale Egyptian affiliations: Egyptian fashioned names of persons, circumcision as a marked covenant procedure, and mobile sacred structure that is characterized in a manner that likens to the elite field structure in Egypt. This reworded the confrontation of Where are the traces of millions? To the question of where are the remains of an ethnically separate minority which since became central? It also serves to clarify the reasons certain passages of the Bible retain the strangely particular priestly interests, and others of them appear to be more local to Canaan.

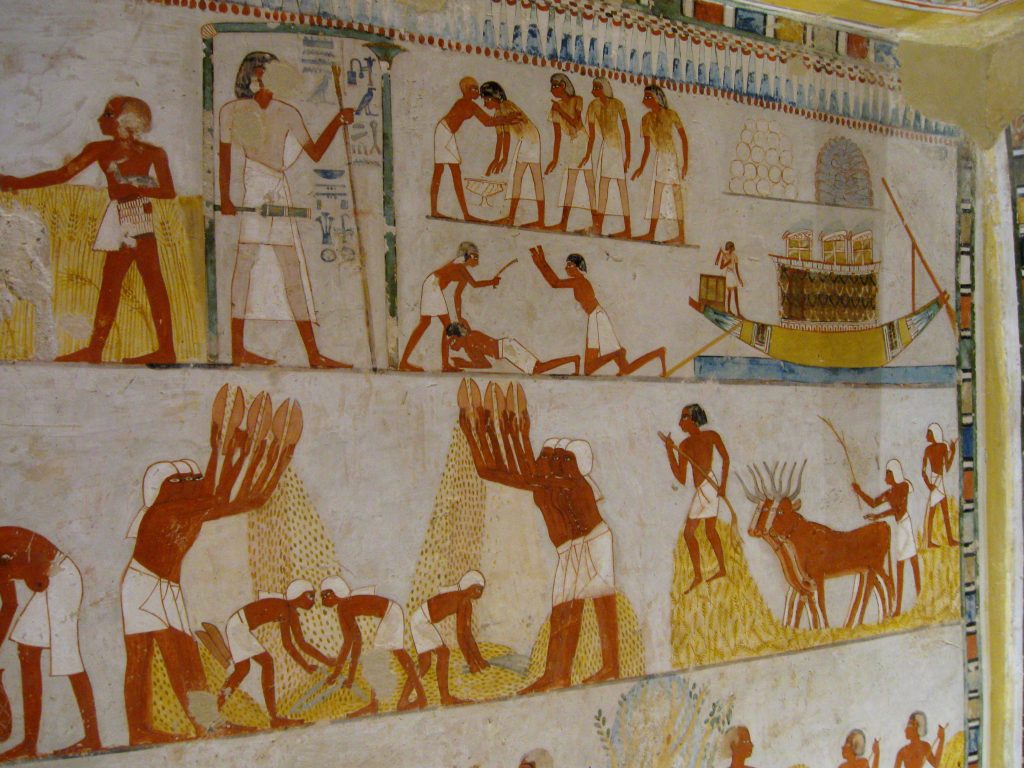

5. Brickmaking and the administrative information that is on par with being forced to labor

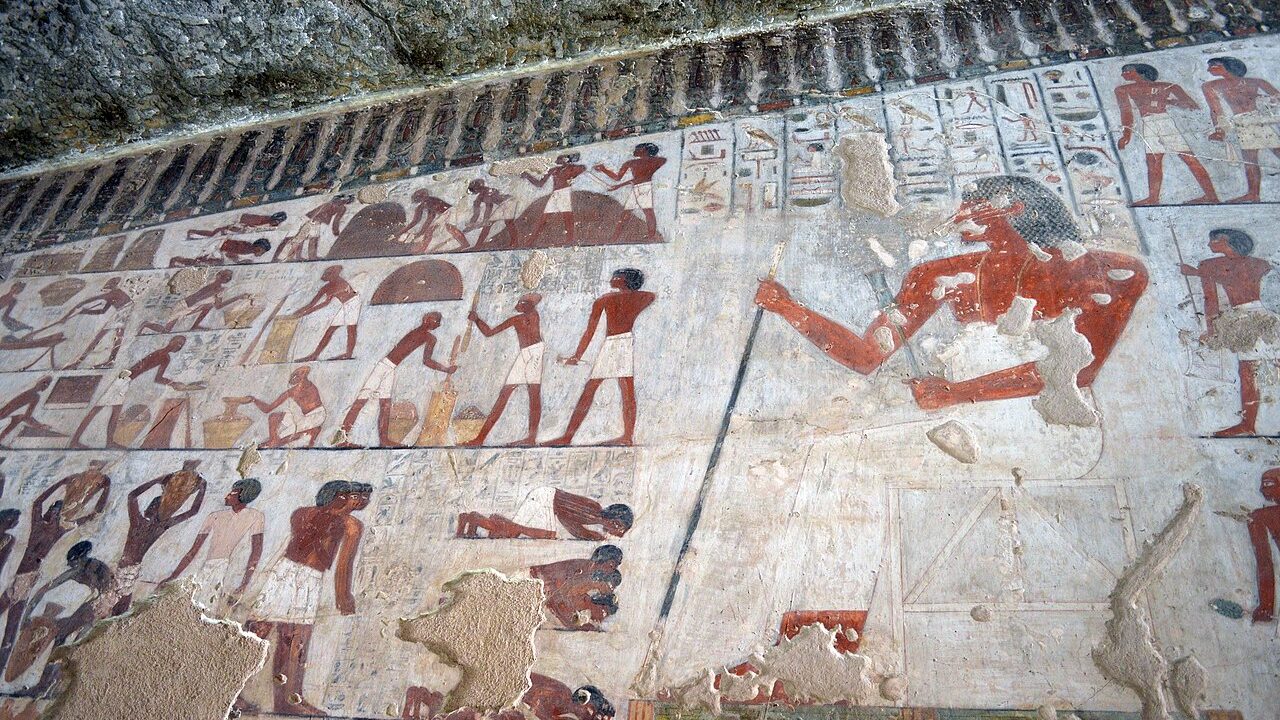

Egyptian literature and the artworks indicate that Semitic speaking peoples were present in Egypt in numerous capacities even as slaves. An iconic shot found in the tomb of the vizier Rekhmire depicts foreign prisoners at work producing the bricks, an imagery parallel to the labor image used in Exodus. The administrative tone of the task is maintained in written sources also: quotas, overseers, punishment, and the reliance on straw in the production of mud-bricks.

A commonly quoted example is an account of Ramesses II-era that talks of 40 taskmasters and a daily target of 2,000 bricks, which puts the process of brickmaking into the same order of organization at which Exodus portrays the system. This is not to call the workers with any form of confidence Israelites, but to demonstrate that the labor world Exodus purports was in the past in New Kingdom Egypt as a home.

6. A newly discovered border fortress which re-lights the logic of the detour in Exodus

Exodus gives the reason as to why a passing company should not follow the most direct open water course: the route was guarded and unsafe. A recent finding assists in making that piece of logistical scenery less literary and more border reality-like. A 3,500-year-old Egyptian fortress was discovered by archaeologists at Tell el-Kharouba in the north of Sinai; it occupies an area of approximately 8,000 square meters and has a length of wall that measures more than 100 meters and 11 towers. Whichever he decides to say about the magnitude of Exodus, fortified lines such as this explain why an unguarded body may bypass the militarized border of Egypt instead of crossing it directly.

7. Delta names, which duplicate Egyptian geography and not subsequent fancy

One of the most neglected pieces of evidence of Exodus is the frequency of its acting like a travel text prior to the time when it turns into a miracle story. Study of the eastern delta and the Isthmus of Suez has narrowed the geographical discourse, matching biblical names with Egyptian place names. One synthesis is that the pre-crossing itinerary may be based at the delta, towards the marshy lake district, and that Succoth may be identified with Tjeku in the Wadi Tumilat, and a subsequent turning point may be established by a grouping of subsequent border place names based on waterworks, forts and canals. The reward is pragmatic: when archeology labors in silty flood area, a logical landscape can still be created using the names that suit the correct area and the correct type of frontier.

None of these hints compel one to a particular conclusion, and none of them eliminates the literary shaping which made Exodus a founding story, as opposed to a mere diary. However, observed collectively they form a more solid image: Semitic-speaking groups in Egypt, labour organization reflecting the texture of the text, border security that justifies the route decisions, and Egyptian stories that resonate with the motifs of inner turmoil and exile. What comes out is not a mystery which was solved, but a story written down which seems more and more attached to the world it is narrating.