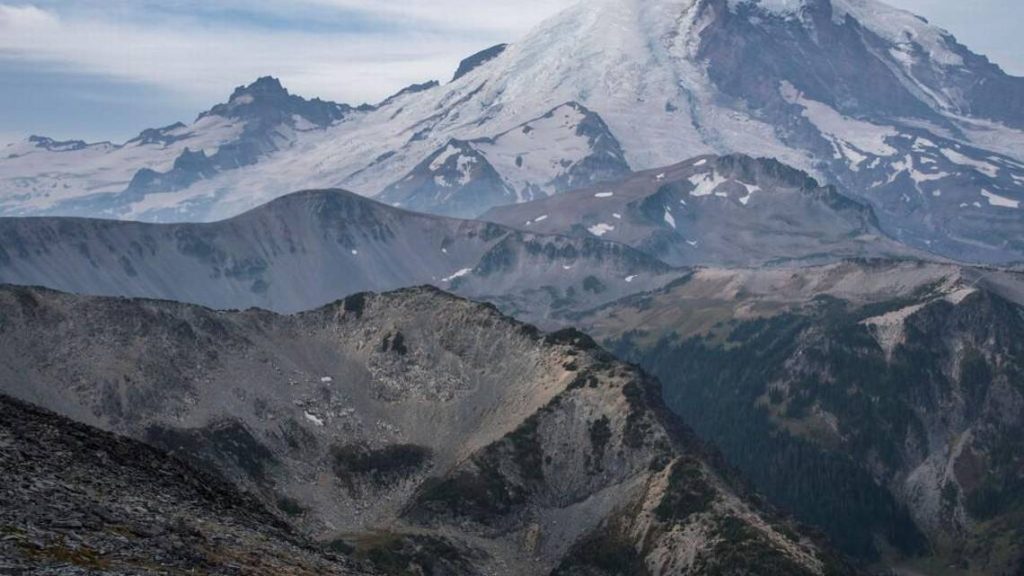

If your morning coffee was the only thing shaking in Washington this week, think again. Mount Rainier just experienced its biggest earthquake swarm since 2009, and though the ground is indeed shaking, there’s no cause for concern, experts say. But when one of America’s best-known volcanoes begins to make a racket, it’s natural that residents, emergency planners, and geology enthusiasts will sit up and ask themselves: what’s happening beneath those glaciers?

Mount Rainier’s earthquakes in recent times have attracted attention throughout the Pacific Northwest, where under the peak, hundreds of small quakes have spread out. While experts are keenly observing as much, the true tale is about attempting to know what these swarms are indicating, how towns prepare for them, and why this volcano gets so much respect. The following is a closer look at the new swarm, the dangers, and the careful practices that protect humans.

1. User research: The 2025 Earthquake Swarm: What Really Occurred?

On the early morning of July 8, 2025, earthquake networks recorded a series of small earthquakes near the summit of Mount Rainier, with the largest being a magnitude of 1.7. The quakes varied from 1.2 to 3.7 miles below the surface and were so subtle that no resident in the region detected any of them, the USGS Cascades Volcano Observatory reports. The rhythm reached a few per minute but then relaxed to a less frantic beat. Hundreds of quakes within a few days is not normal, but not abnormal enough; the last big swarm was in 2009.

2. Is an Eruption Imminent? Here’s What the Science Says

Despite all the hubbub, scientists say it in a nutshell: there is no indication of an imminent eruption. The Pacific Northwest Seismic Network and USGS reinforced that the volcano is still in Green (Normal) alert level. There has been no deformation of the surface, no detected gas emissions by seismics, and no infrasound data suggesting flowing magma. The majority of these swarms are caused by hydrothermal activity, hot water and gas moving under the surface, rather than the rise of new magma. As the USGS described it, “Mount Rainier usually experiences about nine earthquakes in a month,” and swarms “every now and then once or twice a year, though this one is larger than normal.”

3. Why Do Earthquake Swarms Occur at Mount Rainier?

Mount Rainier is prone to seismic activity due to its geology. The mountain mass, glacial cover, and hydrothermal system that is active produce ideal conditions for small earthquakes. USGS describes how the majority of these quakes result from fluids moving under the mountain and bumping into faults, and not by rising magma. The last eruption at Mount Rainier occurred approximately 1,000 years ago. In spite of this, the mountain remains a “Very High Threat” volcano because of its stature, dangers, and proximity to major metropolitan areas.

4. The True Menace: Lahars, Not Lava

Lava is not the worry for Mount Rainier either. Rather, geologists lose sleep worrying about lahars, high-velocity mud-and-water-rock slurries that flow down valleys at pulse-pounding rates. As volcanologist Jess Phoenix explained to CNN, “Mount Rainier keeps me up at night because it threatens the neighboring communities so badly.” Twice as much glacial ice as Colombia’s Nevado del Ruiz (location of a 1985 lahar disaster that killed more than 23,000), Rainier’s capacity for destructive mudflows is enormous. They can travel to populated areas in 30 minutes.

5. How Communities Prepare: Land Use and Zoning

Hazard reduction begins with intelligent land use. In Pierce County, Washington, urban growth boundaries and zoning requirements restrict high-density development and key infrastructure in lahar hazard areas. Keeping something from being constructed somewhere is one of the most effective methods to protect people, experts say. But sometimes it is not easy, cultural identity, economic necessity, and the temptation of sweeping views all compel the developer to build in areas of hazard. That is where constant public education and notification about the risk come into play.

6. Engineering Solutions: Dikes, Dams, and Diversion Channels

Where there are already people and property located in the area of hazard, engineered protection systems are the solution. Sedimentation dams, dikes of exclusion, and armored channels can contain or deflect lahars, giving time to evacuate and minimize damage. The best example is the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ activity at Mount St. Helens since 1980, though these do require periodic maintenance and can foster a false sense of security if not managed properly. As the specialists warn, “risk is eliminated or reduced only for events smaller than the ‘design event.”

7. Lahar Warning Systems: High-Tech and Low-Tech Strategies

The lahar warning system at Mount Rainier serves as a model for volcano-risk zones. It was equipped in 1995 with expert seismic sensors, radio telemetry, and warning sirens to signal threatened communities downstream. People at risk sites have charted evacuation pathways and are part of periodic drill exercises. The system is able to provide individuals with between 12 minutes and 2 hours’ notice to evacuate, depending on their location. Human observers are still in some places, waiting to hear the distinctive growl of an incoming lahar from one ranger as “like a freight train rolling down the canyon.”

8. Clear Communication and Drills

Warning systems are effective only if individuals know what to do in case the sirens sound. Firm, clear communication and routine evacuation drills make a “culture of safety.” The 1985 Nevado del Ruiz disaster revealed the horrific results when warnings are not received or heeded. In Washington state, communities and schools drill evacuation so everyone knows the quickest way to safety and what the warning indicators are.

9. Strengthening Resilience: Recovery and Long-Term Planning

Even with the best planning, sometimes disasters occur. Prevention is impossible without recovery planning. After a lahar, citizens require strong systems of rescue, shelter, and reconstruction. Preplanning alternate routes for transportation, standby sites, and citizen involvement in recovery planning are suggested by experts. The objective: not just to survive, but to recover more resiliently, with safer use of land and improved hazard perception for the future.

Mount Rainier’s earthquake swarm last year is a reminder to live close to a volcano: remain vigilant, but not fearful. With advanced monitoring, intelligent land use, strong warning systems, and a preparedness culture, Pacific Northwest communities are demonstrating how to transform earthquake anxiety into chances for resilience and safety. The mountain might shake, but because of science and planning, the region is prepared for whatever lies ahead.