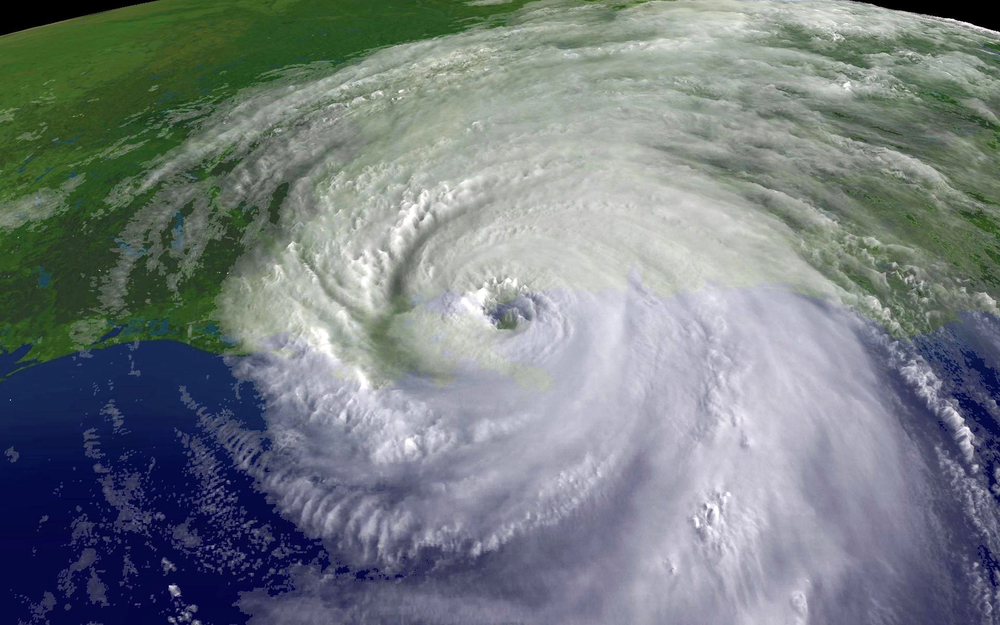

Twenty years after Hurricane Katrina, the sores remain seared water stains on red brick facades, left-behind families perched atop roofs, and a city laid waste not just by water and wind, but by fault lines in the very institutions meant to protect it. More difficult to address is how many of those fault lines persist even as climate change is playing an increasingly high-stakes game with every American coastal metropolis.

1. Warnings Missed and Plans Left Afoot

Katrina’s devastation wasn’t a surprise it was foreseen. Twelve months previously, FEMA’s “Hurricane Pam” drill ominously imagined catastrophic flooding, stranded citizens, and clogged hospitals. “The whole idea was Hurricane Pam was to teach,” explained Ivor Van Heerden at the time with LSU’s Hurricane Center. But, as Senator Joe Lieberman more recently put it, “preparations for Katrina were appalling.” When the hurricane came, evacuation protocols broke down, communications collapsed, and federal agencies grappled with unintelligible command structures.

2. Engineering Failures That Became Fatal

Long before August 2005, scientists warned that the levees of New Orleans were too low and in some spots built on weak soil. Katrina’s storm surge didn’t just overwhelm defenses it shattered them in over 50 locations. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers later acknowledged “faulty and antiquated engineering techniques.” Add to that decades of wetland loss 34 square miles a year the city’s natural storm buffers were already gone. As coastal geologist Gregory W. Stone put it, “Wetlands and barrier islands are the first line of defense. That means places like New Orleans would be more susceptible to flooding.”

3. An Emergency Response System Unprepared for Catastrophe

Katrina demonstrated how an system planned for “typical” disasters failed when faced with disastrous situations. Federal, state, and municipal duties got mixed up, mission objectives bogged down in red tape, and equipment like buses and medical units never arrived when needed. “Time equals lives saved,” Coast Guard Admiral Thad Allen warned, but bureaucratic delays wasted precious hours. Though the National Guard and the Coast Guard moved swiftly to respond, FEMA leadership full of political appointees lacking disaster experience found it difficult to adapt.

4. Social Inequities Shaping Who Returned

The storm’s aftermath was as disproportionate as its blow. Research shows that neighborhood recovery varied wildly by income, race, and tenure. Insured homeowners recovered quickly; renters, especially in low-income and minority neighborhoods, never returned. By mid-2006, the population of New Orleans was older, whiter, and less poor than before the storm giving witness to what sociologists call the “Matthew effect,” in which pre-storm disparities are magnified in recovery.

5. Unexpected Long-Term Impacts

Economist Tatyana Deryugina found that some displaced citizens quickly earned more than similar counterparts who stayed because they moved to more stable economies. Others, particularly from the hardest-hit zip codes, enjoyed no such benefit. Health outcomes for aging and disabled survivors also improved, not because of better care in New Orleans, but because relocation placed them in better conditions. All these results muddy the concept of “recovery” as simply returning home.

6. Climate Change Raising the Bar for Preparedness

The Katrina lessons are colliding with a new reality: warmer oceans and sea-level rise are intensifying storms. Studies have shown that wetlands have the potential to lower storm surge loss by up to 15%, yet coastal development continues to pave them over with asphalt. Along Galveston Bay, ten years of development and wetland loss increased possible storm surge loss by 34.6%. As Deryugina warns, “Once a disaster happens, our response is very good, but we must be doing more before disasters hit.”

7. The Role of Private and Community Response

Amidst state failure, the private sector from Walmart’s voracious supply raids to the Salvation Army’s shelters acted rapidly and effectively. Grass roots traditions like New Orleans’ second line parades became displays of cultural resilience, honoring the dead while showing the city that it would persevere. “Our thing is celebrating their lives the idea that this community will come back one day,” said Lower Ninth Warder Robert Green.

8. What Resilience Really Takes

Resilience isn’t levees and trucks it’s connections between people, equitable recovery policies, and political will to invest before disaster. That is restoring wetlands along with reinforcing floodwalls, investing in low-income housing recovery as assertively as infrastructure, and making evacuation plans accessible to the non-vehicle-owning and cashless. It means embracing new tools, from AI-powered storm simulation to community-based practice drills, to drive a transforming climate.

Katrina cost the most money of any hurricane to have hit the country, but its true cost was measured in lives uprooted and faith betrayed. The question now isn’t going to be if another storm comes, but whether or not the nation has learned how to protect its citizens when it does.