Can a millennia-old story bear the prints of actual events? The book of the Exodus, which is central to Jewish beliefs and is integrated into Christian and Islamic mythology, has been debated by both sides of the debate between those who believe that it is the historical record of the beginning of Jewish people and those who believe it is myth. However, an increasing amount of archeological discoveries, ancient writings and textual studies are changing the discussion.

The texts of the Egyptians, the bible and cultural remains have been discovered recently and have been found to converge surprisingly. These hints are not the assertions to demonstrate all the details of the biblical narrative, however, they present an interesting mosaic – one where political turmoil, migration, and religious change are united. These discoveries can provide those with interest and expertise in religious history with a deeper and more detailed insight into the process of the interplay of memory and history.

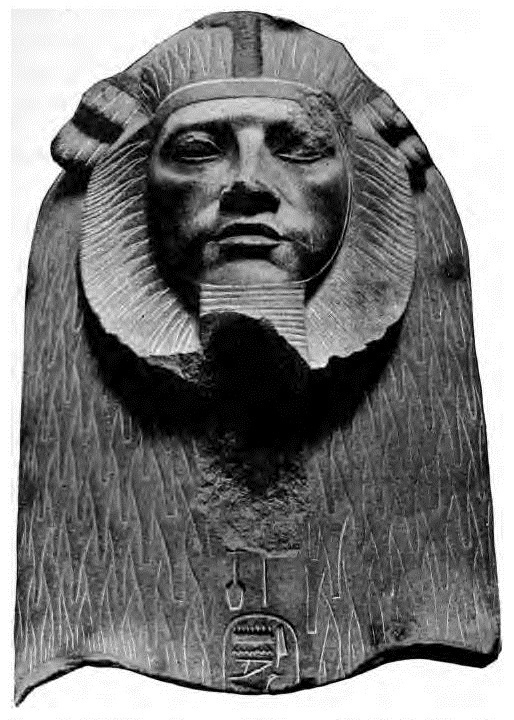

1. Osarseph and the Exodus Parallel of Manetho

Egyptian historian, Manetho, who was fortunately preserved by Josephus, tells of a revolt of a priest called Osarseph against Amenophis, the Pharaoh. This society, which is said to be that of lepers, joined forces with the Canaanites who were called the Hyksos and they destroyed temples and they did not believe in Egyptian religion. Moses was later named Osarseph. The storyline, of an internal minority merging outside forces, conflicting with Pharaoh, and being sent away, almost replicates the book of Exodus 1:10. It has been pointed out that this narrative shares much in common with the biblical text in terms of its political fears and it is hypothesized that it might share a commonly understood cultural memory.

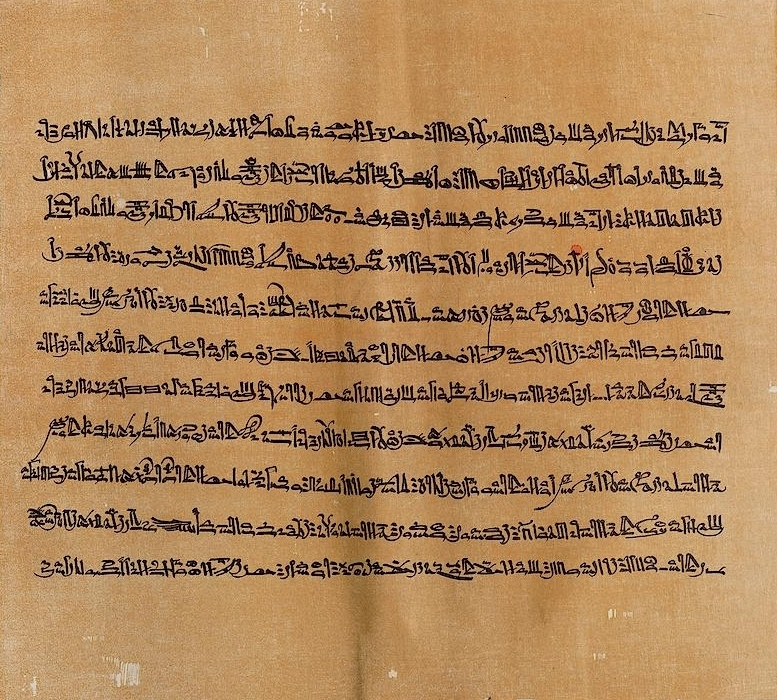

2. Great Harris Papyrus and the Usurper Haru

The Great Harris Papyrus describes Egypt following the demise of Queen Tausert in 1188 BCE when a Canaanite or Syrian ruler was named as Haru. He broke the Egyptian gods, levied taxes on the land and invited foreign allies. It was later brought back to order by Pharaoh Setnakhte who sent the followers of Haru away. The themes in this episode foreign-led rebel, religious rejection and expulsion are echoed in the Exodus story and place it within a reasonable historical context at the close of the 19th Dynasty.

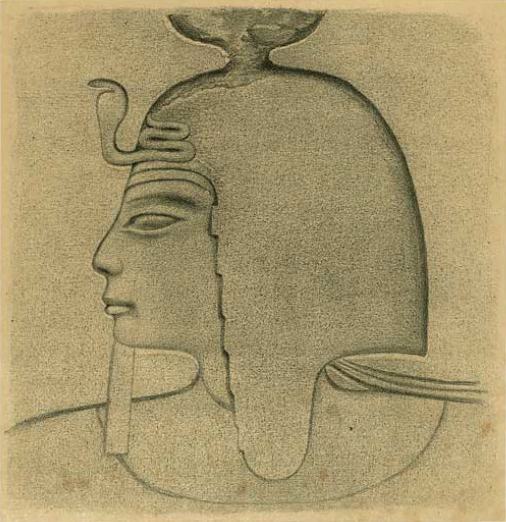

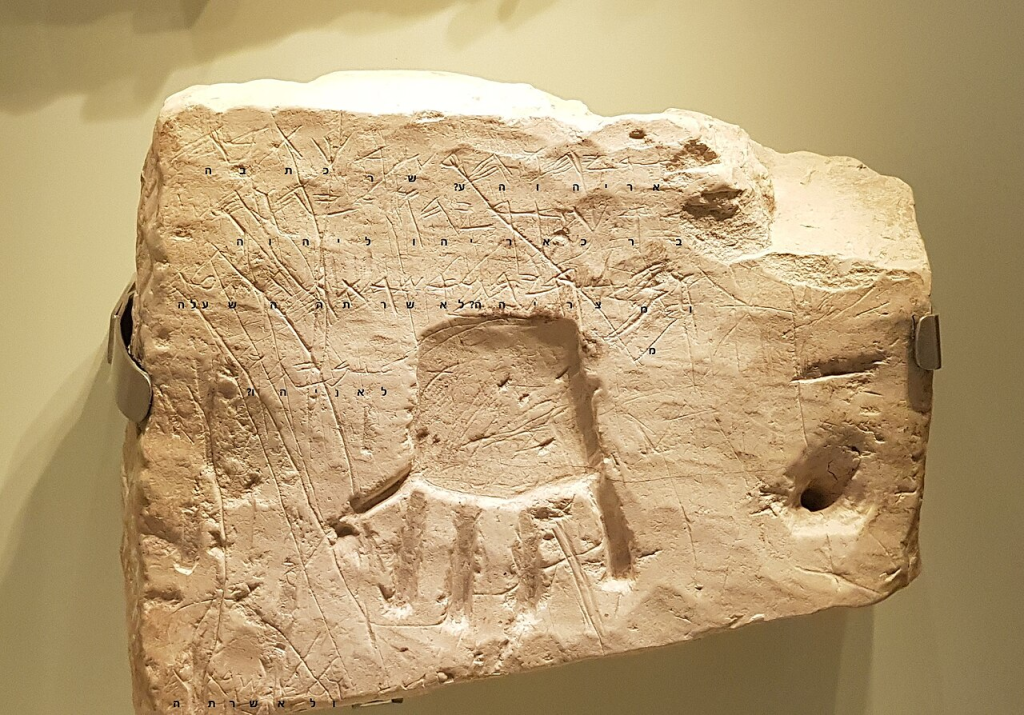

3. Flight Like Swallows of Elephantine Monument

The second-year stele of Setnakhte on Elephantine Island metaphorically talks of fugitives escaping, the swallows fly away, not to pay the mercenaries with silver and gold. This describes imagery of Exodus 12: 35-36, in which Egyptians provide precious metals to Israelites as they leave. The similarity in the motif of abrupt and fear-led escape also reinforces the connection between the Egyptian sources and the biblical account.

4. Levites as the Exodus Core

According to Biblical scholar Richard Elliott Friedman, it can be proposed that the Exodus did not involve a huge number of Israelites but all Levites. Levites had Egyptian names such as Moses and Phinehas and adopted Egyptian traditions such as circumcision and made the Tabernacle like the battle tent of Pharaoh Rameses 2. Such cultural indicators indicate a true Egyptian background and the Exodus tradition was transferred to the Israelite world by the Levites.

5. Songs of Miriam and Deborah

The Song of Miriam, which is set in Egypt, has a song of deliverance without even mentioning Israel as a nation, whereas the tribe of Levi is not mentioned at all in the Song of Deborah, which was composed in Canaan. This fact lends credence to the theory that Levites remained in Egypt when Deborah was there. Being the two oldest biblical texts, the difference in their contexts provides infrequent insights into the disbeliever fusion of the story of the Exodus into the national identity of Israel.

6. Traces of Egyptian culture in Israeli Worship

Egyptian influence is observed in the writings of Levites, which stressed on circumcision, reception of foreigners, and the design of the Tabernacle. These aspects are absent among non-Levite sources. Such customs selectively attest to the fact that it was only Levites that had resided in Egypt and that traditions were imported into the religious life of Israel- a very small, but significant cultural artifact.

7. Unification of El and Yahweh

Israelite tribes were assimilated by Levites and brought Yahweh worship to people who were devotees of El, the high god of Canaan. The two are synonymous in Levite sources in Exodus 3:15 and 6:2153, which was a theological merger that led to the emergence of monotheism. Had this merger not been made, the course toward one deity of the Israelite religion might have taken a long time–or never been taken.

8. Place Names and Archaeological Corroboration at Ramesside

Egyptian literature of the Ramesside Period lists names of Pi-Ramesse, Pi-Atum, and (Pa-)Tjuf the equivalent of biblical Pithom, Ramses, and Yam Suph. These place names are not found to be named jointly until the 13 th -11 th centuries BCE, which coincides with the period many scholars put the Exodus in the timeline. This onomastic accuracy indicates that the biblical narrative carries with it original geographic recollection of the time.

9. The Four-Room House in Thebes

In western Thebes, archaeologists discovered the house of a worker in the 12th century BCE that follows the design of a four-room house of Israelites in Canaan. The wattle and daub material used in its construction instead of stone suggests its availability in Egypt as early as the Ramesside Period and points at the fact that perhaps Egyptian workforce and proto-Israelite populations (possibly those related to the Exodus) were connected.

Although no artifact can be conclusively used to prove the existence of the Exodus, the combination of Egyptian and biblical sources, as well as cultural evidence, makes the historical background possible. These hints disclose a story which has been influenced by political revolution, immigration, and theological revolution. To the faithful, they add to the spiritual legacy of the Exodus; to historians, they present a precious consistency of the Bible and the archaeological record. Whichever way, the past voices both an ancient and longstanding voice.