Answers to story are not messages that go through history. They are more music: reiterated, rewritten, and even confused with the same song.

Readers are frequently struck by the fact that sections of the story of Jesus: miracles, healings, betrayal, death, and return, sound all too familiar in comparison with older myths of the Mediterranean. The New Testament writings were composed at about 50-100 CE, when Egypt, Greece and Rome had amassed literary wealth of sacred story. Parallels can be very vivid, but the study has also demonstrated that similar does not necessarily imply copied, and a common theme may conceal quite different meanings.

Such figures are often placed in opposition to Jesus and the comments made about what the parallels bring to light and where they fail.

1. Osiris

Osiris has been presented as an example of death and restorative power and his cult is deeply connected with the afterlife judgment. It is that similarity, death, persisting power, moral accountability, that idealizes Osiris as a point of comparison.

But the resemblance strangles and unstrangles by definition. The Osiris myth is inseparable to funerary cult and survival of the deceased in Egyptian religion; a number of researchers point out that it is not similar to the New Testament argument on bodily resurrection. One of the most quoted summaries observes that Egyptians never believed in bodily resurrection in the Christian meaning though they were saying so eloquently when it comes to life after death.

2. Horus

Horus is recurrently compared to Jesus, since his mythology has the elements of protection, curing, and struggle with the destructive forces. In contemporary retellings, an additional layer of beliefs is added: virgin birth, disciples, miracles, etc. and arranged in a compact set of Christian-resonant bullet points.

The comparison continues to be valuable to the extent that it is not in one-to-one matches but in the manner that the two traditions employ savior figures to convey safety, legitimacy and cosmic order. The point where the comparison is deceptive is the one at which various Egyptian sources are condensed into one biography which reads like a gospel composite.

3. Asclepius

The Greek god of medicine, Asclepius, is the closest to Jesus in the aspect of the gospels being left to linger on the subject of healing as a public demonstration. The healing cult and the temples of Asclepius were a formidable religious rival in the Roman world; some researchers have remarked on the interchangeability of savior and physician.

A particularly concrete overlap is the symbolism of the serpent. An analysis of the John Gospel indicates healing divider Rod of Asclepius and the biblical tradition of the bronze serpent in the broader Mediterranean medical-religious context, and places the Christian language in context.

4. Dionysus

The use of Dionysus is commonplace since the ritual use of wine is made holy by Christianity and the Fourth Gospel begins the public displays of Jesus with a wedding in which water is changed to wine. That is exactly what a traditional audience could have heard as an epiphany: divinity embodied in the form of plenty.

Classical sources too keep a record of wine being used in Dionysian festivals with three empty basins under seal in Elis having been full of wine. The resemblance may make reading sharp without making the difference vanish: in John, the sign heralds the presence of identity and belief in Dionysian tradition, the presence of the god in season, and the cultic power of the god.

5. Attis

Attis is often among the dying and rising god, particularly in later Greco-Roman reTellings of the story when springtime ritual takes center stage. That frame might help, as a map of repeated religious words – loss, come-back, renewal.

But a contemporary scholarship keeps warning about the dangers of applying dying and resurrected deity as one widespread prototype. An extended overview of the discussion explains the shift of the scholarly community towards a rejection of the idea that a general pattern-hunting approach suits the early sources and the question of whether or not the category suits the early sources well.

6. Adonis

Adonis is associated with the spring and reproductive prosperity of the seasons, in this way comparisons are inclined around the death and a revival, and not narrative mirrors. It is the attachment of cult practice to specific locations and memories- how landscape gets made sacred by repetition.

That is important in Bethlehem, where subsequent Christian tradition makes the focal point of the birth of Jesus. According to archaeological and historical discourse, the church was constructed around an important cave by Constantine and that this location had a sacred location as early as mid-third century prior to modern pilgrimage tourism. Some of the earlier Adonis worship claims are included in other narratives but are most effectively treated as a series of overlapping sacred geography, rather than the direct indication of substitution.

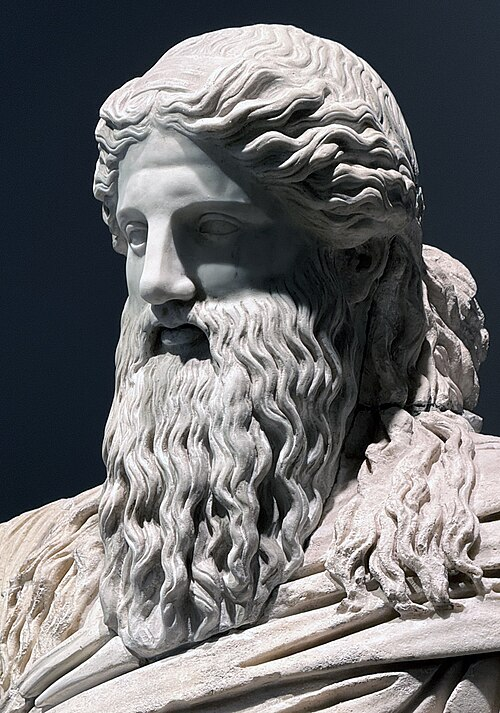

7. Heracles

Heracles is like Jesus in another octave: God-father, early dangers, unusual trials, and subsequent elevation. It is not a narrative similarity, but a similarity, which is primarily theological, but which is constructed by ancient cultures concerning a figure who suffers, endures, and is welcomed in the circle of gods.

It is also there that the comparison remains the most sincere. The work of Heracles is no sermon, and his world no morality; the common ingredient in both is the primitive love of meaning that is made by the trial.

8. Romulus

Romulus comes into the discussion with the founding myths: miraculous birth, endangered infancy, and destiny related to the identity of a people. His narrative indicates how the idea of salvation can be a civic and not a spiritual one- the genesis of Rome as holy memory.

The analogy to Jesus can help enlighten the process through which the stories of origin construct power. It may also deceive when it causes Jesus to become national founder instead of someone that early Christians placed in the scriptures of Israel and in the hope of apocalypse.

When viewed collectively, these similarities expose a pattern with regard to human narrative, namely, communities resort to a particular set of images such as wine, healing, betrayal, death, vindication because these images have an emotional dimension. It is only the assertion made to those images by each tradition that changes.

In the gospels the recognizable motifs are combined into a horizon of history, not a horizon of season: a narrative which has the direction of judgment, restoration and a new world. It is that distinction–even stronger than any list of confirming details–that the best comparisons are initiated.