Most powerful art is the art of telling the truth. In Hollywood, the truth about mental illness has most often remained beyond reach, swamped by stereotypes, clichés, and sensationalism. But occasionally, a film breaks through the din, offering an account that feels honest, nuanced, and human. These are the movies that don’t simply fall back on mental illness as a plot device they explore it with sensitivity, empathy, and respect. They aim to break down stigma, expose the complicated realities, and still manage to create compelling, memorable narratives.

Whatever the situation whether the inner resilience of a teenager, the collapse of a perfectionist, or the complex relationship between siblings these movies prove that honesty is as engaging as any twist of plot. This is a well-curated list of film highlights that not only amuse but also open up crucial conversation about mental health.

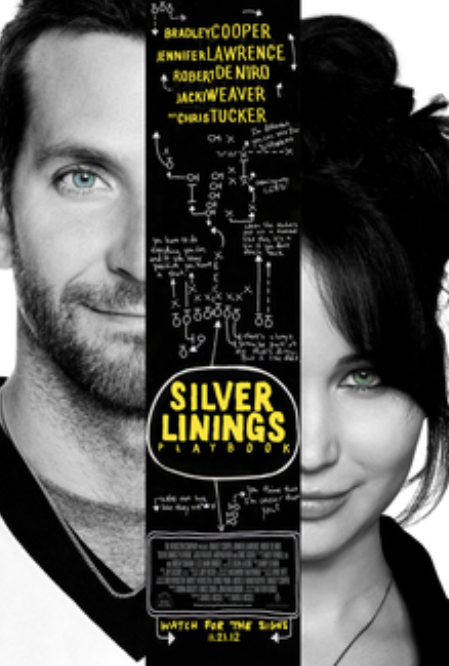

1. Silver Linings Playbook – Bipolar Disorder with Heart

David O. Russell’s film based on Matthew Quick’s novel introduces bipolar disorder to the romantic comedy genre without sanitizing it. Pat Solitano’s (Bradley Cooper) volatility, impulsiveness, and not wanting to take medication are shown side by side with his desperate need for human connection. Tiffany (Jennifer Lawrence), grappling with loss, is both reflection and lifeline. While some critics note the film shies from more medical specifics, it strikes the emotional truth of living with bipolar disorder something the media likes to caricature to an extreme. As highlighted in research into representations of bipolar, too many screen representations stretch for unpredictability or menace; rather, in this case, the focus is on the richness of human nature and not stereotypes.

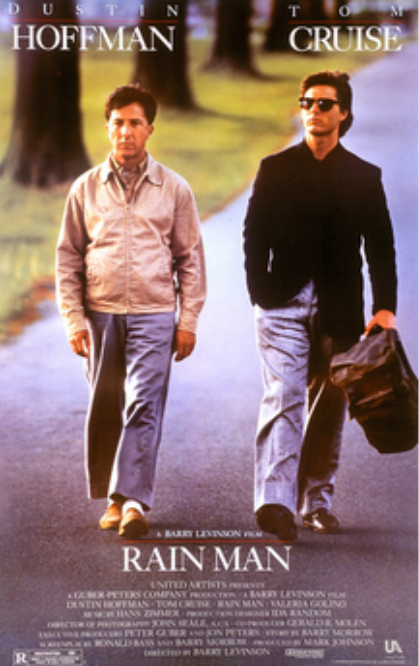

2. Rain Man – Autism Beyond Stereotypes

Autism was seldom portrayed in mainstream films until Barry Levinson’s ‘Rain Man’ debuted in 1988. The film presents Dustin Hoffman’s Raymond as a more complex character than his savant skills; it takes time to reveal his discomfort with change, sensory sensitivities, and need for routine. Charlie’s (Tom Cruise) change transcending seeing his brother as an obstacle to seeing he’s a human being bears a strong similarity to what most experience the first time they encounter developmental disorders. Despite having its dated moments, it was a step toward depicting autistic individuals as loving, development-capable, and as agents.

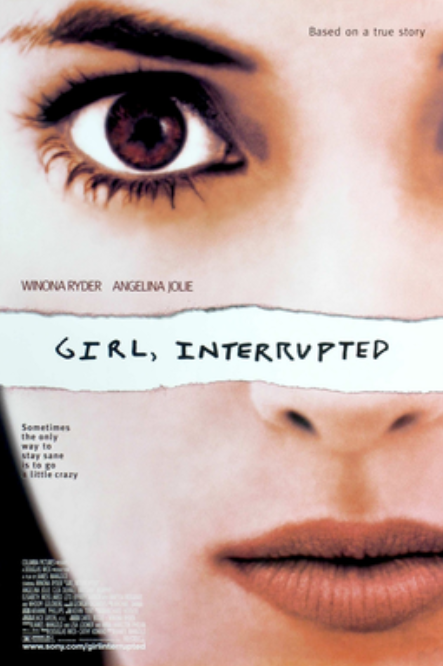

3. Girl, Interrupted – Unflinching Truth of Psychiatric Intervention

Based on Susanna Kaysen’s memoir, this 1999 drama dives into the chaotic, fragmented process of healing. Winona Ryder’s Susanna takes us through a 1960s mental hospital with a wild cast of characters, including Angelina Jolie’s Lisa, a sociopath played without cartoon villainy. The movie resists reducing the characters to diagnoses and reveals their humor, anger, and vulnerability instead. This kind of layered representation remains rare especially for women given that eating disorders and other sicknesses are typically represented through the thin SWAG stereotype of “thin, White, affluent girls,” erasing so many lived experiences.

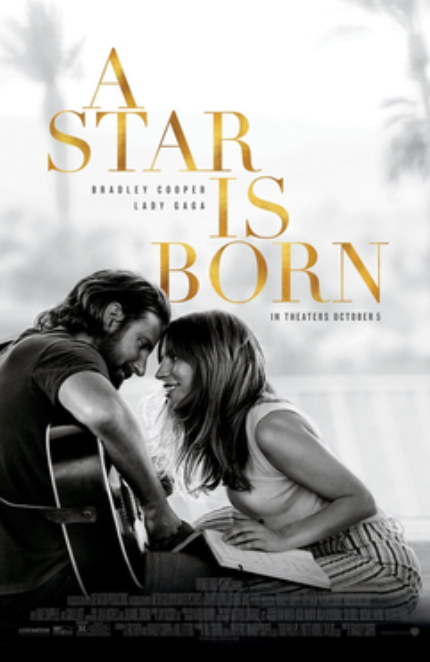

4. A Star Is Born – Addiction and the Cost of Stardom

Bradley Cooper’s directorial debut strips away star glamour to show how addiction, trauma, and public life can overlap. Jackson Maine’s (Cooper) alcoholism is intertwined with hearing loss and years of unresolved suffering. Fame here isn’t redemption it’s a pressure cooker. As examined in research on the psychology of fame, the constant scrutiny, identity fragmentation, and loneliness can enhance vulnerabilities. The tragic ending of the film confirms how unresolved difficulties triumph over even the strongest love.

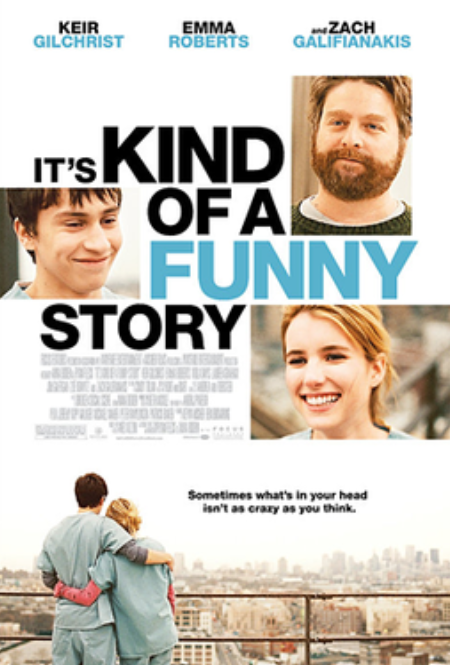

5. It’s Kind of a Funny Story – Teen Depression with Hope

This dramedy coming-of-age deals with teen mental health without trivializing it. Craig’s (Keir Gilchrist) short time in the adult psych ward after a suicide attempt is an airy, witty, and touching exploration of depression. The humour never disrespects the seriousness something that’s crucial in light of the way teen depression has been portrayed and how it either supports or estranges teen audiences. As studies of teen mental health and cinema have shown, seeing characters with whom they can identify makes teens feel less alone and more receptive to seeking help. The movie’s ending isuring but hopeful reminds us that recovery is a journey, not a magic pill.

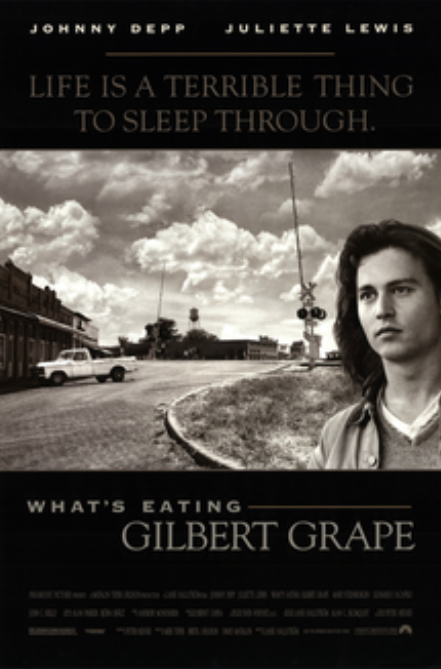

6. What’s Eating Gilbert Grape – Caregiving and Hidden Struggles

Lasse Hallström’s rural drama is as much an emotional labor drama as family love drama. Gilbert (Johnny Depp) has the heavy responsibility to look after his mentally disabled brother Arnie (Leonardo DiCaprio) and his obese mother Bonnie, who is depressed and grieving. Sympathy from the movie in portraying obesity as a mental disorder is rare, especially given the culture of media to resort to ridicule. It is also true that caregivers’ mental health matters, something generally not very important to note in storytelling.

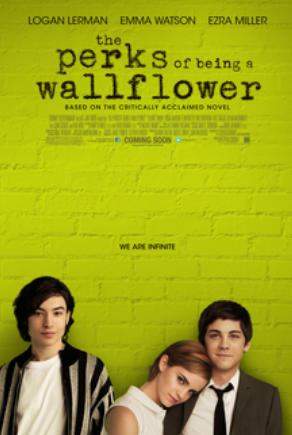

7. The Perks of Being a Wallflower – Cautious Clues of PTSD

Stephen Chbosky’s own book adaptation captures the understated, oft-invisible clues of teen trauma. Charlie’s isolation, flashbacks, and hesitancy to share are gradually revealed as signs of PTSD. The movie refrains from melodramatising his pain as teen angst and shows how trust and friendship enable healing to ensue. In relation to the teen depression movie genre, the film is noteworthy for its tempered equilibrium of hope and honesty.

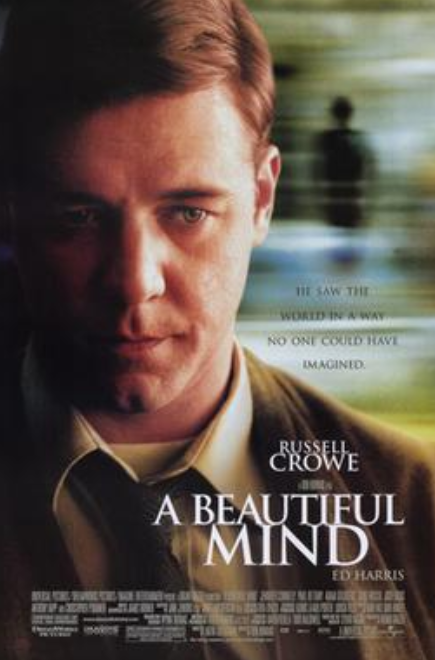

8. A Beautiful Mind – Schizophrenia from the Inside

Ron Howard’s biopic of John Nash uses cinematic perspective to place viewers in paranoid schizophrenia delusions, hallucinations, and all. While the real Nash’s symptoms were primarily auditory, the visual presentation of the film makes losing touch with reality intimate. Most importantly, it shows the work of family support and the long-term management involved in dealing with schizophrenia, if indeed it puts the recovery time under strain. As mental health practitioners attest, treatment is never as Hollywood shows – instant – but the emphasis on resilience and adaptation is strong.

9. Black Swan – Obsession, Perfectionism, and Collapse

Darren Aronofsky’s psychological thriller combines reality and fantasy to depict Nina’s (Natalie Portman) disintegration under stress of obsessive-compulsive tendencies, eating disorder, and performance stress. Although artistic license is used, the film is informed by the truth that OCD is far more than a “quirk” about being clean a myth cultivated by most screen portrayals. As OCD specialists insist, illustrating the ‘why’ of the compulsions is important; here, Nina’s rituals are associated with intrusive fear of inadequacy, so her breakdown is appallingly believable.

These films show us that when mental illness is portrayed with dignity and complexity, it can turn an already-great story into one that’s unforgettable. They challenge tired stereotypes, foster empathy, and remind us that there’s always a human being behind the label who dreams, who’s flawed, and who’s resilient. To cinema-going audiences and to mental health advocates as well, they’re not movies brain food for thought.