“They just want to be left alone.” In a nutshell, U.S. District Judge Fred Biery distilled a centuries-long debate into an emotional refrain that gets its first sympathetic ear in this hyperpolarised era. His latest move to delay Texas’ Ten Commandments classroom bill isn’t just another courtroom fight; it’s part of a much larger American story about religion, liberty, and the First Amendment.

State by state, Republican lawmakers have been attempting to reinstate the Bible as a book in public schools, inspiring lawsuits, appeals, and ardent arguments back and forth. The Texas case, in all its rich judicial opinion and high-profile political players, offers us an instructive snapshot of where this fight is and maybe where it’s going.

Here’s a closer examination at the seven most compelling arguments of this nascent legal and cultural battle.

1. The Judge’s Blistering and Witty Reprimand

Judge Biery’s 55-page ruling wasn’t reliant on Supreme Court history alone; it braided together quotes from Greta Garbo to Billy Graham, even conjuring up a teenager stammering through a question with a teacher about how to “do adultery.” The punchline served a purpose: forcing religious texts into classrooms might make teachers and students uneasy, with unpleasant side effects. His final conclusion? The law probably violates the First Amendment prohibition on government promotion of religion.

2. Families of All Faiths Rose Up

Plaintiffs were not uniform. They were clergy, Jewish, Christian, Unitarian Universalist, Hindu, and non-religious families who shared a common concern: the law would make children conform to religion. Lead plaintiff Rabbi Mara Nathan said, “Children’s religious beliefs should be instilled by parents and faith communities, not politicians and public schools.” Judge Biery concurred, threatening the law would compel students towards “veneration and adoption” of a state-suggested doctrine.

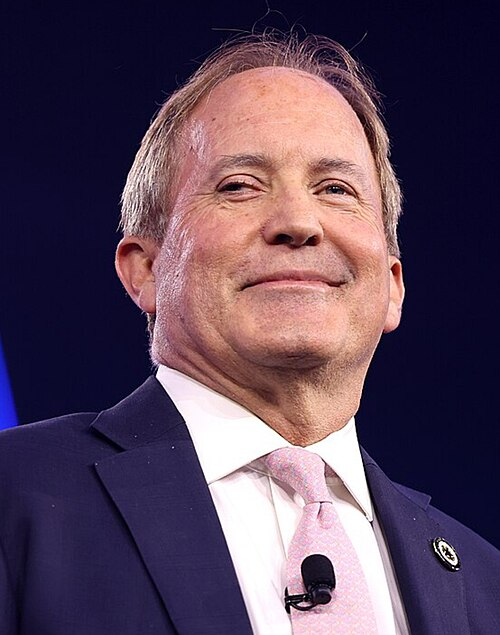

3. Texas Aims to Fight Back

Then Attorney General Ken Paxton subsequently promised to appeal, deeming the Ten Commandments “a cornerstone of our moral and legal heritage.” He had brushed aside separation-of-church-and-state objections as a “bogus claim” and instructed districts not affected by the injunction to go ahead with displays. His action follows a wider conservative policy of appealing these cases to a Supreme Court more sympathetic to religious displays in public places than in previous decades.

4. The National Push and Pushback

Texas is not alone. Louisiana and Arkansas enacted similar laws in 2024–2025, and both have at least partially been enjoined. In Arkansas, a court ruled there was no historical tradition of permanent postings of the Ten Commandments in schools, a dispositive consideration under the Supreme Court’s new “history and tradition” test. Concurrently, at least a dozen other legislatures have introduced similar bills, from Bible readings to “In God We Trust” posters.

5. The Shift from the Lemon Test to History and Tradition

For decades, the 1971 Lemon test controlled Establishment Clause cases, commanding a secular purpose and avoiding advancement of religion. That was upended in 2022 by Kennedy v. Bremerton, as the Court substituted a “history and tradition” approach. It is for these reasons that states like Texas believe there is an opportunity to reinstitute laws that were reversed in instances like 1980’s Stone v. Graham. To date, though, lower courts have wondered whether history is on the side of classroom mandates.

6. The Risks for Religious Freedom in Schools

The grievance of the critics is that government-sponsored religious symbols are excluding kids who don’t accept those beliefs, and they feel less embraced in their schools. The ACLU cautions that public schools must be spaces where all children of all faiths and none are able to go freely without compulsion. As Heather L. Weaver summarised after a Louisiana decision, “Public schools are not Sunday schools, and they must welcome all students, regardless of faith.”

7. What Might Occur in the Supreme Court

The Court has a 6–3 conservative majority, and support is expecting that the Court would be open to permitting such laws and drawing on the rationale of Van Orden v. Perry, where a Ten Commandments monument was permitted on grounds of the Texas Capitol. Even among the conservative justices, some reservations have been expressed, particularly where school children are involved and are at their most vulnerable. Whether the Court goes broadly, narrowly, or sidesteps this issue is uncertain.

The Texas decision is a powder keg of an even broader constitutional fight far from finished. As appeals continue and other states move forward with similar bills, the seesaw between respecting the past and safeguarding religious neutrality in the classroom will continue to challenge the courts and America’s promise to both religion and liberty.