A remarkable 37% of UK adults have now sought AI chatbots for support with their mental health or wellbeing, according to polling commissioned by Mental Health UK. The spike evidences both the increasing ease of access to such tools and a growing strain on NHS services, as waits for therapy extend into months or even years. While many cited feeling less alone, and even avoiding crises because of AI, findings also revealed some worrying risks that urgently need safeguards.

1. Why People Are Turning to AI Chatbots

The reasons for turning to AI included ease of access, cited by 41% of the people who took part, followed by ‘long NHS waits’ at 24%, with ‘discomfort discussing mental health with friends or family’ also at 24%. Some feel that AI offers anonymity and a non-judgmental space. Two-thirds of users found chatbots beneficial, while for 27%, they made them feel less alone. Compared to women, men were more likely to use the AI in such a manner-42% against the 33% of the latter-which perhaps suggests that the tools are reaching groups previously less likely to seek help.

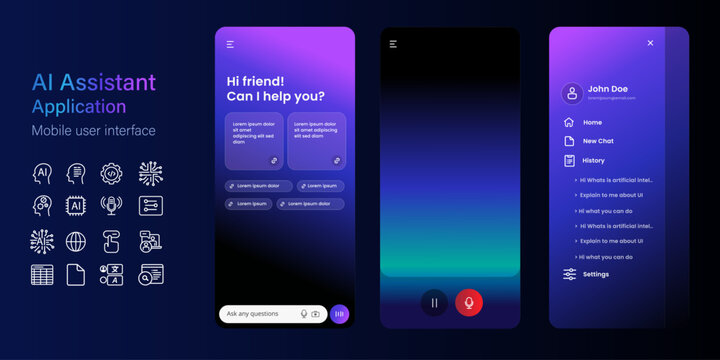

2. General-Purpose vs. Mental Health-Specific Tools

A full 66% of participants used general-purpose platforms like ChatGPT, Claude, or Meta AI rather than mental health-specific apps such as Wysa or Woebot. The specialist ones often have inbuilt crisis pathways and frameworks to underpin them clinically, while the general-purpose ones may use unverified sources. Wysa, for example, uses breathing exercises and guided meditation, escalating to helplines if the users show indications of self-harm.

3. Documented Benefits

One in five users reported AI helped prevent a possible mental health crisis, with 21% reporting receiving useful information on how to manage suicidal thoughts, including signposting to helplines. A study by Dartmouth College indicated that the use of chatbots can reduce symptoms of depression by up to 51% over four weeks, with trust and collaboration levels similar to human therapists.

4. Serious Risks Identified

That same survey showed that 11% of users received harmful suicide-related information, 9% triggered self-harm or suicidal thoughts, and for 11%, symptoms of psychosis worsened. Research by RAND and others shows that large language models can be inconsistent in their response to intermediate-risk queries about suicide, sometimes providing unsafe advice. At Brown University, researchers have cataloged 15 ethical risks, including “deceptive empathy” and poor crisis management.

5. The Call for Safeguards

Brian Dow, chief executive of Mental Health UK, warned: “AI could soon be a lifeline for many people, but with general-purpose chatbots being used far more than those designed specifically for mental health, we risk exposing vulnerable people to serious harm.” The charity’s five guiding principles include that AI draws only from reputable sources, the integration of tools into the mental health system, and a human connection at the heart of care.

6. Ethics Oversight and Regulation

The National Counselling & Psychotherapy Society has provided the first relational safeguards in the UK for AI mental health tools: interventions should be time-bound, supportive rather than directive, adjunctive to therapy, transparent about their limits, user-autonomous, and safeguarded with clear escalation to human help. International reviews echo these concerns, with privacy, bias, and accountability highlighted as core ethical pillars.

7. Best Practices for Safe Use

Experts recommend selecting clinician-vetted chatbots created for mental health, ensuring that crisis protocols are in place, and not disclosing any identifiable personal information. These services must be put into perspective: No AI chatbot is cleared for diagnosing or treating mental health disorders, and their use should augment, not replace, professional care. As Stephen Schueller of UC Irvine says, “Innovation in this space is sorely needed, but we have to do innovation responsibly by protecting people.”

8. Bridging the Gap Without Replacing Humans

While AI may provide psychoeducation, coping strategies, and be available 24/7, it lacks the relational depth of human therapy. Counselling research is consistent in finding that the therapeutic relationship is the strongest predictor of outcome. In the words of Meg Moss from NCPS: “AI can help with a great many things, but it can never replace the safety, trust, and human connection that only people can provide.”

The growing use of AI for mental health both reflects a need and presents an opportunity: a need for accessible support in an over-stretched system, and the opportunity to design safe, ethical, effective tools. The challenge facing all policymakers, developers, and advocates alike is clear: earning trust through transparency, protecting vulnerable users, and ensuring that technology enhances rather than erodes the human connections at the heart of mental health.