For more than three hundred years, the galleon San José had lain buried beneath Caribbean waters, her story hovering between myth and fact. But for the first time, physical treasures from that fabled vessel saw daylight-and with them, new layers of mystery, history, and geopolitical drama.

1. Long Overdue Recovery

At 600 meters deep in water, from November 16 to 18, Colombian researchers extracted, together with the Navy and cultural authorities, a bronze cannon engraved “Sevilla,” three golden macuquinas, and a delicate porcelain cup from the galleon wreck site. President Gustavo Petro attended the resurfacing of the items, proof of the national relevance of the operation. The items now undergo their conservation process in a special laboratory as part of the second stage of investigation project “Towards the Heart of the San José Galleon.”

2. The Ship’s Fateful Journey

The San José was built in 1698 and was the flagship of the Flota de Tierra Firme – the Spanish Crown’s monopoly fleet linking Cadiz with the New Kingdom of Granada and the Viceroyalty of Peru. Leaving Peru in 1707, it had on board a cargo of royal treasure-chests of emeralds, 11 million gold and silver coins, and other items-precious resources destined to finance the War of the Spanish Succession.

History records that it never arrived in Spain. On June 7, 1708, near Cartagena, the British squadron under Admiral Charles Wager intercepted the galleon. Accounts differ: Spanish sources say an explosion during the battle sent her down; British records indicate she sank without exploding.

3. Scientific Sleuthing Beneath the Waves

The Colombian Institute of Anthropology and History is analysing sediment samples from the wreck to determine whether battle damage or structural failure doomed the vessel. High-resolution photogrammetry captured by ROVs has already dated coins to 1707, minted in Lima with the heraldic crowns of Castile and León. “Coins are crucial artefacts for dating and understanding material culture, especially in shipwreck contexts,” said Daniela Vargas Ariza, lead researcher.

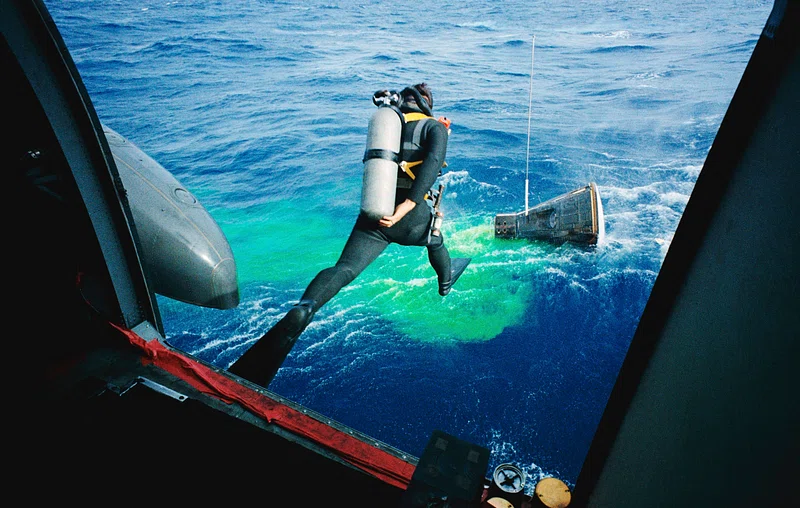

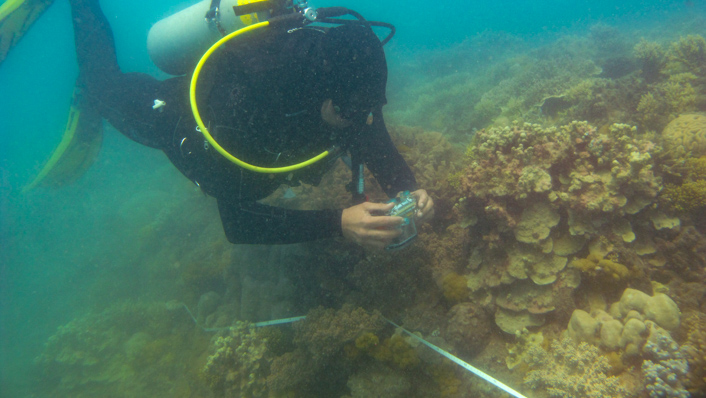

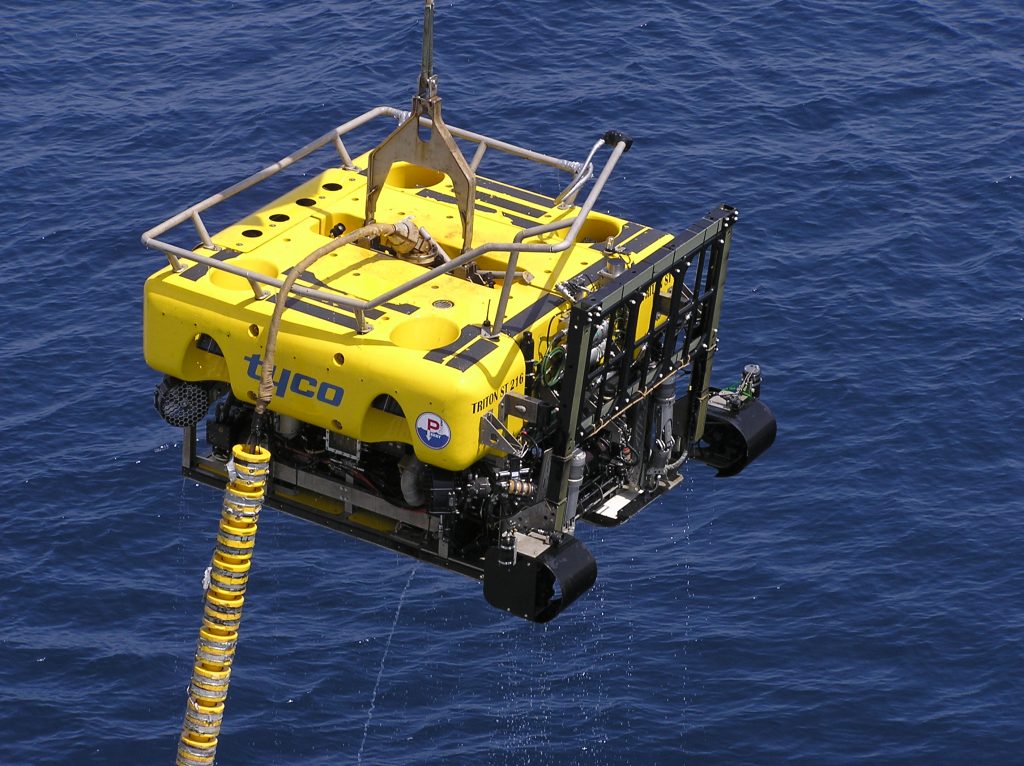

4. Deep-Sea Technology in Action

Modern marine archaeology has really opened up the search for shipwrecks once thought unreachable. The San José lies far beyond scuba limits, in waters that would deter most treasure hunters. Colombian teams, with the support of such institutions as Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, used remotely operated vehicles to non-invasively map the site before recoveries began. The advances in deep-water exploration-from dynamic-positioning vessels to compact, high-performance ROVs-find echoes elsewhere, such as the surveys of Roman wrecks in the Tyrrhenian Sea, whose cargo organization and even post-depositional changes have been revealed with unprecedented clarity by photogrammetry.

5. A Treasure Fleet’s Legacy

The San José was part of a vast transatlantic network. Between the 16th and 18th centuries, Spanish treasure fleets carried royal wealth from the Americas to Europe, often hugging coastlines in order to avoid storms. Yet disasters were common: in 1715, a hurricane off Florida sank ten treasure ships of the Spanish Plata Fleet, killing nearly 1,000 and scattering fortunes that lay hidden for centuries. Events such as these speak to the dangerous nature of maritime trade during the age of sail.

6. The Legal Maelstrom

Ownership claims have multiplied since Colombian naval researchers found the San José in 2015. One US-based salvage company called Sea Search Armada, previously known as Glocca Morra, claims to have discovered the wreck in the 1980s and is claiming $10 billion-half the estimated value of the treasure. Spain insists that the galleon remains its property. Indigenous Qhara Qhara Bolivians said the cargo had been stolen from their lands. That dispute is now before the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague, where international law doesn’t offer any great clarity.

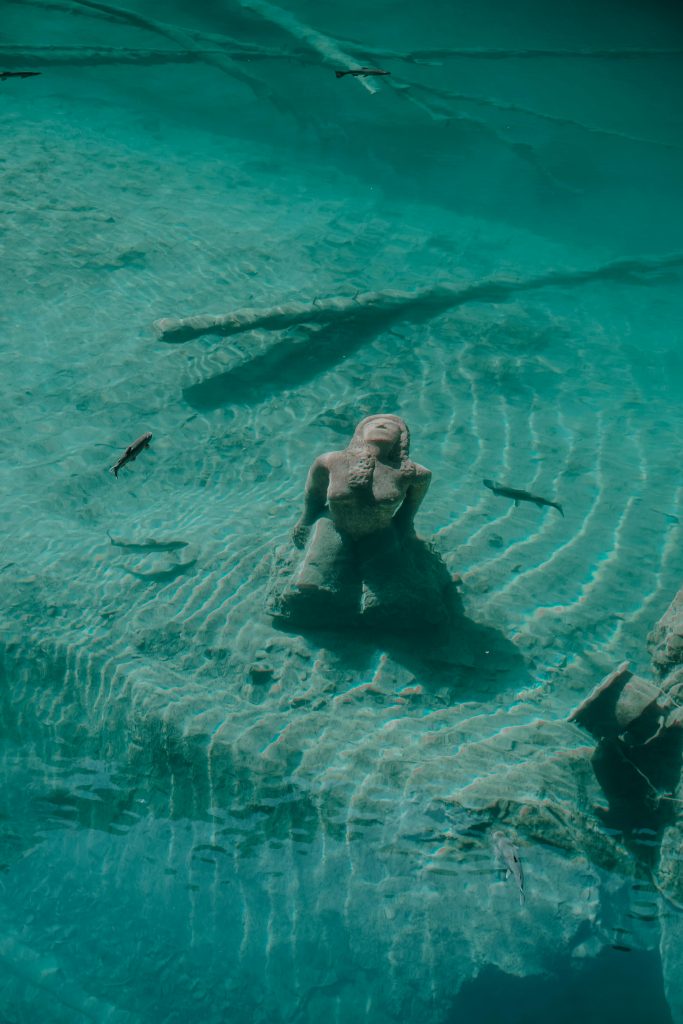

7. Cultural Heritage vs. Commercial Gain

But the government insists this recovery is a cultural and scientific operation, not a treasure hunt. “It is a historic event,” said Culture Minister Yannai Kadamani Fonrodona, one that shows the country’s ability to protect the underwater heritage. Preservationists and historians argue that it is also a mass grave-more than 600 people lost their lives when the ship sank-and should be treated with solemn respect. In the government’s approach, a balance is struck between archaeological study and paying one’s respects to those who perished.

8. What’s to Come Only

the cannon, coins, and a porcelain cup so far, have been retrieved from its cargo. The anchors, jugs, glass bottles, and maybe whole chests of precious metals remain at the wreck site. Yet their exact coordinates remain secret, lest illicit salvagers get wind of them and try to loot the wreck.

Every artifact, while undergoing conservation, has yielded clues about the way the ship was built and what it was carrying, thus yielding further details about trade routes and economic currents in the early 18th century. A better understanding will emerge from the unfolding investigation churning on through turbulent waters of modern geopolitics.