The 1950s often arrive wrapped in chrome and certainly families cruising in big cars, children loose-limbed and sunburned, neighborhoods that felt like they watched over themselves. However, many of the normal activities of the previous decade now feel out of place alongside current legislation. The change is not merely a reflection of more stringent regulations; rather, it is a function of new scientific knowledge, new standards for public safety, and a new understanding of what constitutes harm.

1. Allowing children to move about inside a moving car

In many family photographs and memories, children are seen sitting on armrests, kneeling on seats, or lying across the back shelf below the rear window. The cars themselves lacked seat belts, and child seats, when used, were often intended more for holding the child in place than for protecting the child in the event of an accident. Federal guidelines did not appear until the 1971 child car seat rules, and national guidelines are still more recent. Today, an unrestrained child means citations, mandatory restraint enforcement, and, in extreme cases, child endangerment charges.

2. Handling drunk driving as a remediable embarrassment

The typical 1950s model of a bar-to-home journey was portrayed as a poor choice, not a danger to the public, particularly in small towns where everyone knew each other. Contemporary enforcement is based on quantifiable impairment and specific levels, such as the 0.08% BAC standard for licensed drivers in most states. The consequences extend well beyond a warning, including arrest, licenses, and long-term repercussions that track the driver from one employment to another and through insurance paperwork.

3. Transporting minors in the open bed of a pickup truck

What appeared to be a summer shortcut, with kids sitting on the floorboards of a truck bed or even near a swinging tailgate, now appears to be avoidable trauma waiting to happen. Many places have banned the practice for minors, although this varies widely from state to state, case to case. A stop in the present day can result in a ticket for improper transportation, and an injury can quickly turn into a case of negligence. The “just hold on” approach to safety no longer qualifies as common sense.

4. Dumping used oil, paint, or chemicals on the ground

Maintenance in the 1950s typically left waste dumped in a ditch or behind a garage. Appliances, broken glass, and tin cans were dumped in ravines or empty lots, considered clutter rather than pollution. Today, many of these items are considered hazardous waste, and dumping them illegally can result in fines, cleanups, and criminal charges. The difference is that soil and water are now known to keep receipts for decades.

5. The enforcement of racial segregation as “normal” public behavior

In most of the United States, citizens were active in maintaining segregation by refusing service, asking for a seat change, or calling the police to enforce the “separate” environment. These behaviors were once socially reinforced. Civil rights legislation later made them illegal forms of discrimination, subject to civil liability. The important change is that equal access became mandatory, not optional.

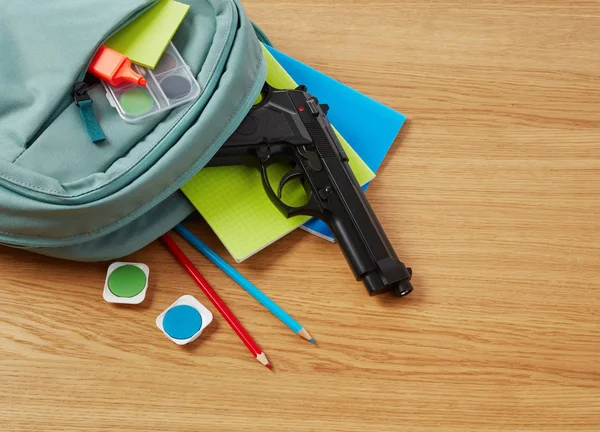

6. Carrying hunting guns into school premises without alarms

In certain rural settings, students brought rifles or shotguns for hunting purposes and stored them in cars, cloakrooms, or hallways. The mere presence of a weapon did not necessarily mean a panic attack. The current standard of school safety policies and state laws considers weapons in schools a serious offense, which is a felony, and thus results in a lockdown instead of a principal’s approval.

7. Marketing toys that modern regulators would seize

The chemistry sets of the middle decades included strong chemicals and delicate glassware, while the dart games and pellet guns emphasized realism over safety. Injury was a part of growing up. Today, consumer protection regulations require testing, warnings, and limits on hazards, and a firm selling the most dangerous forms of these products would be subject to recalls, lawsuits, and regulatory action. The new standard presumes children should outlive their toys.

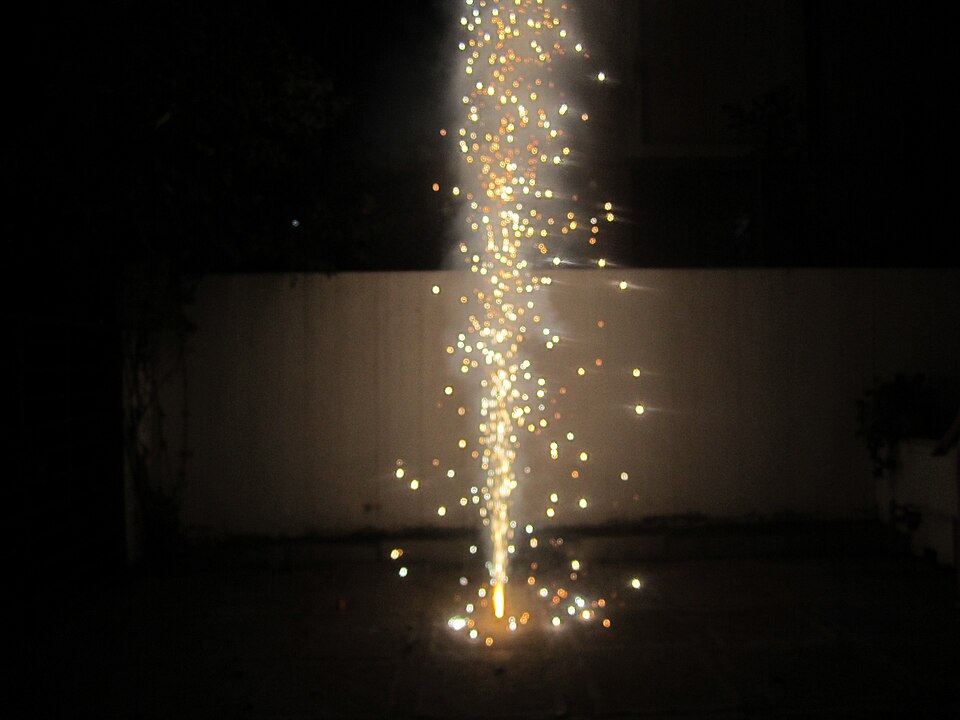

8. Fireworks in densely populated areas

Backyard fireworks displays were once the domain of bottle rockets launched near rooftops and firecrackers set off as jokes, sometimes under the guidance of adults who were simply supervising from the porch. But under fire codes and explosive regulations, what was once a DIY display is now a serious danger, particularly in areas where fires are a quick spread and homes are close together. What was once a summertime tradition could now be a police report.

9. Leaving bruises and welts under the label “discipline”

Physical punishment in the 1950s was often excused as a family matter, even when it became injury. Teachers and neighbors were reluctant to get involved unless the injury was severe. Gradually, the child protection system became more dependent on professional reporting, and the federal system of mandatory reporting was strengthened by CAPTA in 1974. Currently, visible injuries can lead to reporting by professionals, investigations, and criminal charges not as much due to changes in temperament as to the fact that preventable injury is now a public concern.

10. Viewing animal abuse as entertainment or “mischief”

Stories of neighborhood history once dismissed acts of cruelty to animals, tying things to pets, tormenting strays, or fighting pets as a childish phase to be outgrown. The history of the law has been the reverse, from state laws to federal law, including the Animal Welfare Act of 1966. In many places, cruelty to animals is a serious crime, a felony, and a significant predictor of violence. The contemporary standard of the law holds that animals are not playthings for the bored.

The gap between “normal then” and “illegal now” is more than a tale of tougher enforcement. It is also a history of what was learned by society about the physics of injury, about public health, about discrimination, and about the long-term effects of cruelty. Reflecting on these practices, the quieter truth revealed is that laws do not only punish but record what a culture has finally decided it cannot tolerate.