Bad Bunny did not make the Super Bowl halftime stage a blank canvas. He made it an area where Puerto Rican life could be constructed to the full size of the scale, fields, street food, music traditions, family stories, and political memory, and awaited with a keen eye who would pay attention.

Others were so self-evident even on the couch, the pava hats, the piragua cart, the light-blue triangle upon the flag. Others were hurried, concealed in costume, set dressing, and the manner in which the camera lingered on some of the faces. Such are the instances that aid the understanding of why the performance was like a medley less and more so a visual glossary.

1. Opening sugarcane fields resembling a history lesson

The show opened in a terrain that was designed to resemble the sugarcane fields of Puerto Rico, where workers were chopping stalks in the background, and Bad Bunny passed through the set. The imagery linked the partying ambiance with work and colonial extraction, the prolonged streak between the Spanish governance and the industrial level sugar manufacturing that was still at the heart of the decades. The fact sugar represented close to half of the agricultural output in Puerto Rico even in 1964, a point that helps underscore how contemporary that tradition remains, helped in making that point.

2. Fast, readable as a symbol of jibaro identity, pava hats

Backup musicians were dressed in pavas-straw-brimmed hats attributed to the rural life of Puerto Ricans and jibaro culture. Costume plays out on television. Contextually, it is an indicator of who is in the middle: not just celebrity spectacle, but agricultural workers and the culture that is constructed around them.

3. Snacking in the streets that transformed the stage into a neighbourhood

Bad Bunny passed a coco frío cart and a recreated piraguas stand, and during one of the performances, he briefly picked up the shaved-ice snack. Such details act as olfactory memory to the audience that recognizes them: coconut water sold on the street, bottles of syrup in a cart, dessert that is given away without much ado. The performance utilized food as geography- one expedient means of making legible without explaining Puerto Rico.

4. A jersey with Ocasio and 64 on it as personal lineage

The clothing of Bad Bunny instead of relying on one iconic accessory pushed the focus to a name and number. Ocasio was printed on his back with 64, and in a statement to Rolling Stone, he explained the connection: 1964 is the year my uncle Cutito was born, the brother of my mother, and the sports fandom could be transported through them.

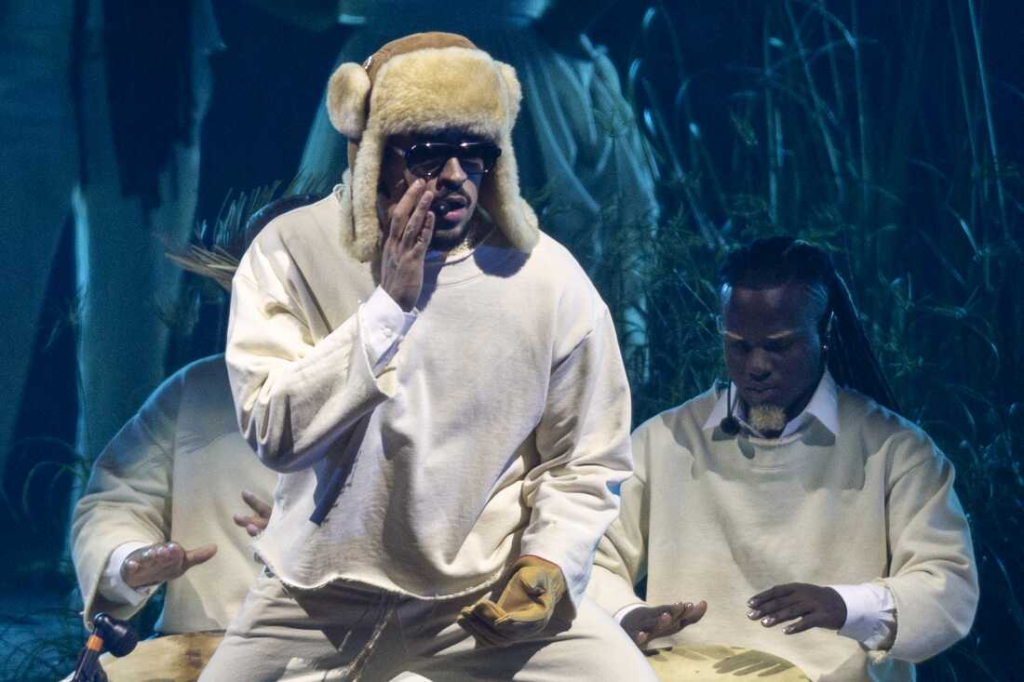

5. A reggaetón roll call which gave the architects credit

Bad Bunny interlaced snippets and mid-medley, making allusions to early Puerto Rican icons: Daddy Yankee’s “Gasolina”, as well as allusions to Tego Calderon and Don Omar. He also informed the audience in Spanish, “You are listening to Puerto Rican music. The barrios and the projects, Painted back as the story of origin, Not exported.

6. Concho the toad, who carries an environmental warning meekly along

Prior to the name of the state of Monaco, the airing transitioned to the character of Concho, who is a part of the world of Bad Bunny, Debi Tirar Mas Fotos. Concho is a symbol of the Puerto Rican crested toad, which is on the verge of extinction, and the cameo served as a miniature PSA within the pop choreography. It was also aligned to the overall theme of the show, what is lost when development and displacement pick up pace.

7. The maga flower was a national bow of Lady Gaga

The wardrobe choice of Lady Gaga in her cameo was slightly intended instead of decorative: a red floral brooch that looked like the maga flower, the national flower of Puerto Rico. Her costume was anchored into the repeated light-blue flashes of the show and the insistence on being Puerto Rican and her symbols on the largest American entertainment arena.

8. A New York storefront mapping the Puerto Rican diaspora

In Nuevayol, the set pieces were transported to a Brooklyn neighborhood that alluded to the Puerto Rican life in New York, with the view of signage of La Marqueta, long-linked to the Latino immigrant trade of East Harlem. It was not about tourism but about continuity how Puerto Rico survives in the mainland by way of markets, music, and institutions of the community.

9. Toñita makes a cameo appearance as a living stand-in to stay put

Behind a pretending bar, Maria Antonita Cay better known as Toñita seemed familiar to most New Yorkers as the proprietor of the Caribbean Social Club in Brooklyn. The cameo was consistent with the lyrical shout-out in the song and tied the issues of gentrification in the halftime show to a particular individual whose business has survived the transition to the neighborhood.

10. The triangle flag of light-blue and chaos of the power-line in El Apagono

In El Apagando, poles of power and fake lines took the center stage and in the next scene, they exploded, which symbolized frustration of consecutive outages, and a weak grid. Bad Bunny also featured a Puerto Rican flag design with a light-blue triangle, commonly used in sovereignty and independence movements as opposed to the dark blue commonly found on reproductions designed by mainstream media. Politic meaning was not dependent on a speech; it lay in the color selection and staging.

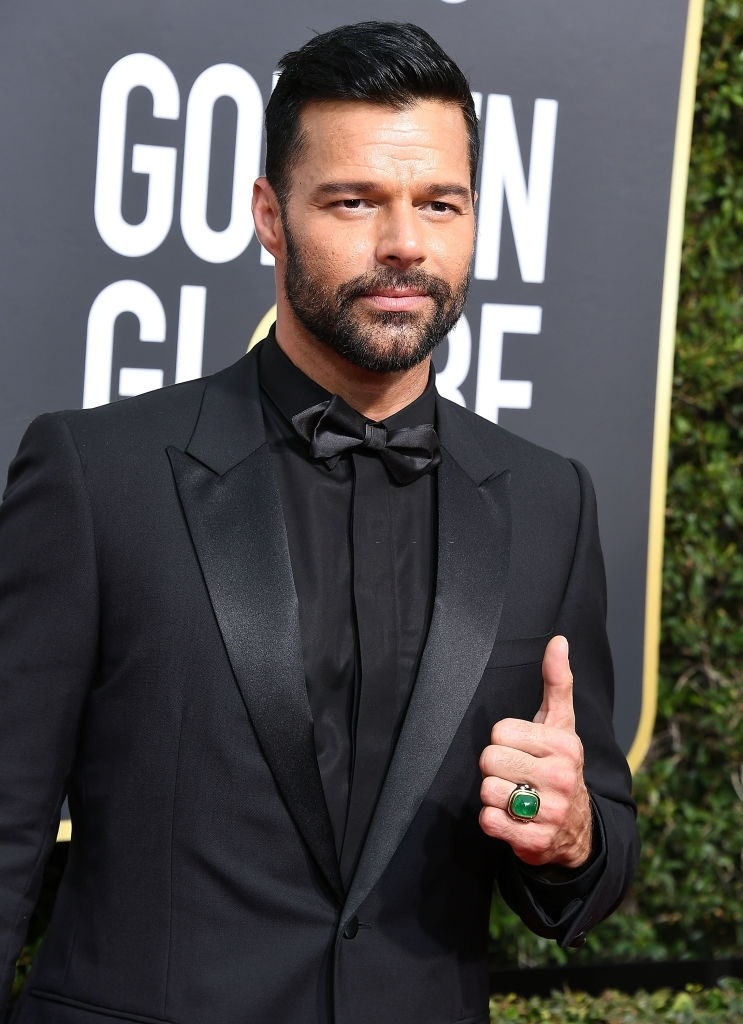

11. The lyrics of Ricky Martin that called gentrification and displacement phobia

In the performance by Ricky Martin, there was a song titled Lo Que Le Paso a Hawaii in which he directly addresses the fears of land and culture loss. The songline that was made prominent in the execution was: They want to steal my river and my beach, too. They desire my neighborhood and grandma to go, and the audience of the Super Bowl is put within the realm of the language of housing pressure, not only celebration.

12. The message written on the billboard that was repeated on Grammy-stage

One of the most obvious hints used in the texts was on a billboard: The only thing more powerful than hate is love. The words were a repeat of the Grammy speech of Bad Bunny who told them, The only thing that is stronger than hate is love. The message in the halftime was a refrain, easy to read, because it was easy, and specific because it could be traced to his official position.

The halftime performance at Bad Bunny was a kind of door opening the culture, family, diaspora, ecology, and politics one by one, only several seconds at a time. The references did not invite all the viewers to follow everything. They rewarded attention.

What remained consistent across the symbols was the same idea: Puerto Rico was presented as lived experience work, music, food, and community rather than a backdrop. That framing is what made the “Easter eggs” feel less like trivia and more like identity, placed carefully in plain sight.