In east-central Wyoming’s wind-swept badlands, the “mummy zone” is a rare geological pocket from which scientists have unearthed a remarkable discovery: a rewriting of what is currently known about dinosaur anatomy. Found are the first-ever evidence of hooves on any reptile and the most complete fleshy profile of a large dinosaur ever reconstructed.

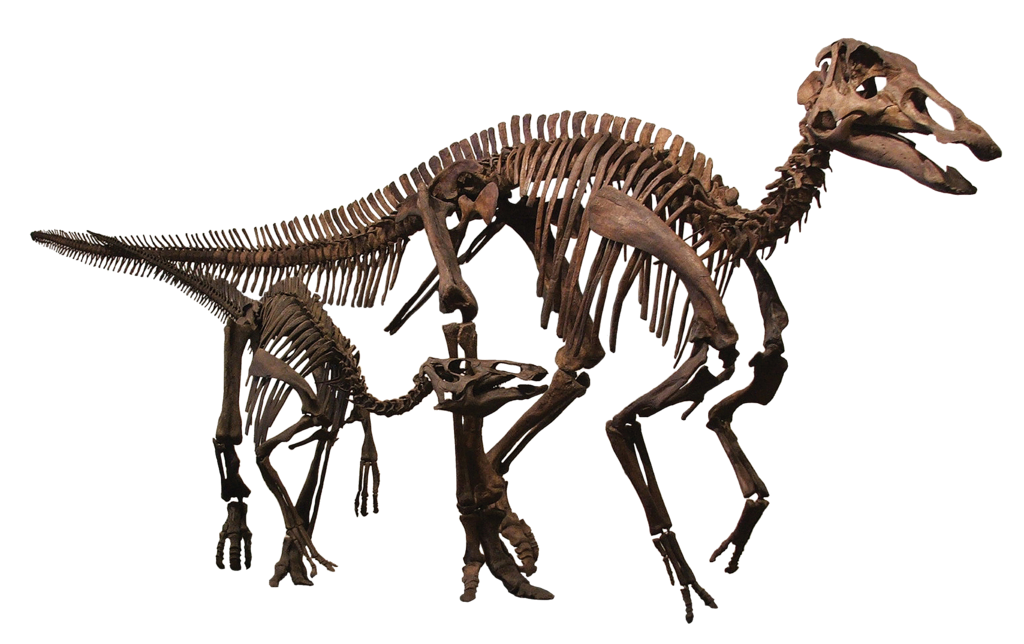

Two exceptionally well-preserved specimens of Edmontosaurus annectens-a juvenile approximately two years old and an early adult-have emerged from the sandstone layers of the very end of the Cretaceous, their skin, spikes, and hooves captured in a paper-thin clay mask preserved during the brief window just after death.

1. A Fluke of Fossilization

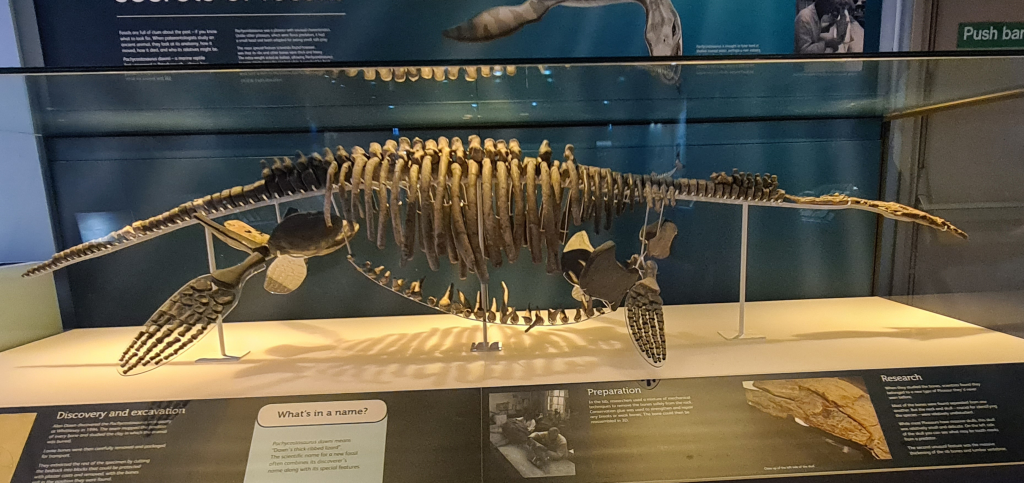

The preservation method, called clay templating, is a phenomenon previously documented only in certain marine environments. Here, the process began when drought-stricken carcasses lay exposed under the sun, their skin wrinkling tightly over bone. A sudden flash flood buried them in coarse sediment, and a biofilm on the surface electrostatically drew fine clay particles from the surrounding matrix. This clay layer less than 1 millimeter thick faithfully recorded every scale, crest, and hoof before the organic tissue decayed away. “This is a mask, a template, a clay layer so thin you could blow it away,” said University of Chicago paleontologist Paul Sereno.

2. Rediscovering the Mummy Zone

Working from century-old photographs and field notes, Sereno’s team relocated the sites where early 20th-century fossil hunter C.H. Sternberg had found the first Edmontosaurus “mummies.” These modern excavations revealed that the zone, less than 10 kilometers across, has produced at least six major mummified dinosaur specimens, including Triceratops and Tyrannosaurus rex. The fluvial sandstone deposits of the compact area seem uniquely suited to preserving external anatomy in three dimensions.

3. The Crest and Spike Row

The juvenile mummy revealed a fleshy crest running along the neck and trunk, merging over the hips into a single row of interlocking spikes that continued to the tail tip. Each spike corresponded to a single vertebra, a configuration rare among reptiles. The adult specimen preserved the entire spike row intact, along with polygonal scales ranging from 1 to 9 millimeters in size. Wrinkles over the ribcage suggest the skin was surprisingly thin for an animal exceeding 12 meters in length.

4. Hooves Before Mammals

The most astonishing discovery was at the adult’s hind feet: three wedge-shaped, flat-bottomed hooves capping the toes. These structures meet the definition of mammalian hooves, yet pre-date them by tens of millions of years. “The earliest hooves documented in a land vertebrate, the first confirmed hooved reptile, and the first hooved four-legged animal with different forelimb and hindlimb posture,” Sereno said. The forefeet bore a single central hoof while the hindfeet combined hooves with a fleshy heel pad a posture combination unmatched until now: unguligrade forelimbs and subunguligrade hindlimbs.

5. Convergent Evolution in Action

This adaptation shares similarities with hoof structures seen in modern horses, goats, and cattle, despite Edmontosaurus being a reptile. Such similarity is another good example of convergent evolution, where the unrelated species will independently evolve comparable traits to meet similar environmental demands. Hooves offer durability, traction, and shock absorption advantages for a large herbivore navigating hard, open terrain.

6. Anatomy Linked to Footprints

CT scans of the preserved feet were fitted to a well-preserved hadrosaur footprint from Alberta’s St. Mary River Formation. It was a perfect match, confirming the hoofed toes’ role in shaping the rounded impressions of the track. This is a very rare conjunction of skeletal and ichnological evidence and provides direct information about how the animal moved.

7. Death in a Season of Extremes

Evidence points to drought as a likely cause of death, followed within days by flooding that buried the carcasses intact. Late Cretaceous seasonal monsoons could shift from arid heat to torrential rain in a perfect sequence for clay templating. The absence of scavenging marks suggests that carcasses were abundant enough never to have been touched, a scenario observed in modern elephant die-offs during severe droughts.

8. A Window into the End-Cretaceous World

Edmontosaurus was the “cow of its day,” living in vast herds alongside Triceratops, Ankylosaurus, and Tyrannosaurus rex. While fossil evidence indicates it was a favorite prey for T. rex, its size and herd behavior made it a formidable target. The hooves may also have helped in both migration and escape, supporting efficient locomotion across varied terrain.

9. Expanding the Search

It not only documents unprecedented anatomy but also provides a methodology for future work: careful field recovery, advanced imaging, and anatomical reconstruction combined to capture extinct life in full detail. Sereno’s team is now conducting targeted searches through Wyoming’s mummy zone and other similar formations, hoping to find more examples of clay-templated preservation.

From the delicate mask of clay that held their form in death to the astonishing evolutionary surprise of their hoofed feet, these Edmontosaurus mummies represent a bridge across the divide between the age of reptiles and the mammalian characteristics of life today. They stand as both scientific marvels and poignant reminders of how fleeting moments in deep time can leave an indelible mark on the fossil record.